By Shannon Gilchrist

The Columbus Dispatch, Ohio

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Natasha Quadlin, an assistant professor of sociology at Ohio State found that after submitting fake applications for real entry-level jobs, employers were much less likely to call back a female candidate with a very high grade-point average than a woman who had slightly less impressive grades.

The Columbus Dispatch, Ohio

Playing up excellent college grades won’t necessarily help a woman seeking a job — and might actually hurt, according to new research from Ohio State University.

Natasha Quadlin, an assistant professor of sociology, set out to determine how much academic performance matters to employers, and especially whether that differs by gender. Her results will appear in the April issue of the journal American Sociological Review.

She found, after submitting fake applications for real entry-level jobs, that employers were much less likely to call back a female candidate with a very high grade-point average than a woman who had slightly less impressive grades.

Men who majored in math and earned the highest GPAs were called back three times as often as high-achieving female math majors.

Past research has found that high-achieving women suffer what Quadlin called a “competence-likeability trade-off” and are unable to be viewed as both at the same time. “Men can simultaneously be judged to be powerful but still be beloved,” she said.

From a survey of hiring managers, Quadlin found that employers gave an edge to female candidates perceived as likeable. The most successful men were seen as competent and committed.

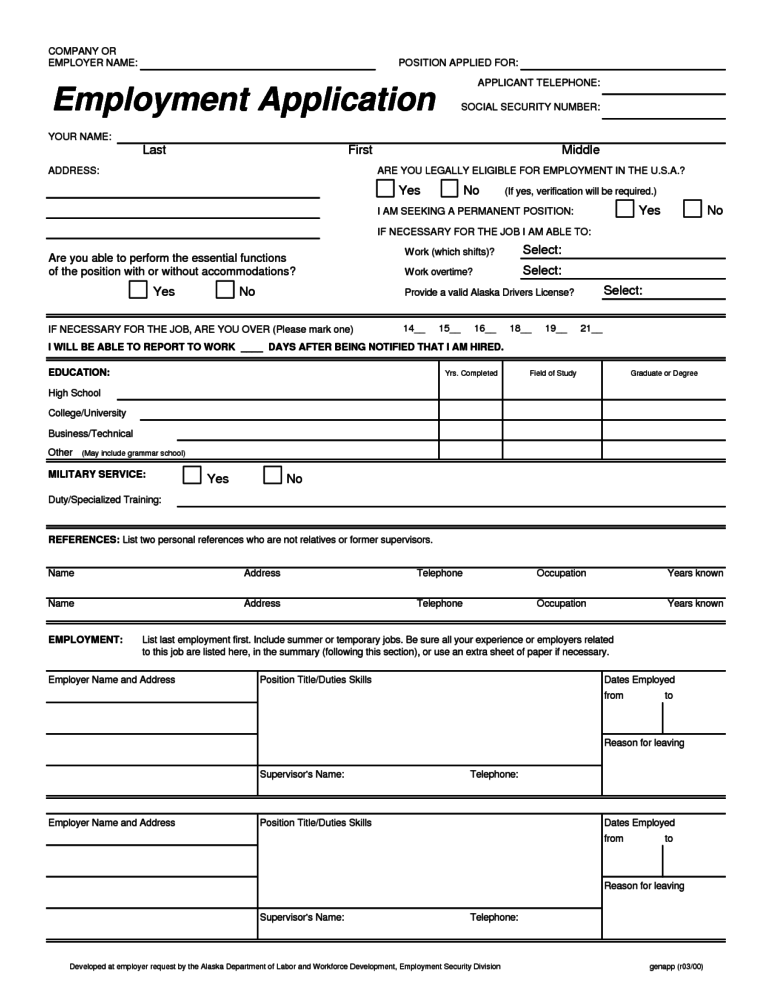

Quadlin sent out 2,106 fictional applications for 1,053 job openings across the country for general, entry-level positions. Gender was signaled by first name; she picked names that were among the top five baby names for the mid-1990s in each region. Surnames were common and didn’t signal race or ethnicity.

She used a random-number generator to assign a college GPA somewhere between 2.50 (C-plus or B-minus average) and 3.95 (solid A average). The fictional applicants all majored in English, business or mathematics at large, moderately selective public universities.

The resumes were extremely similar, including the same number of extracurricular activities and similar work experience.

Overall, 12.9 percent got calls back from their applications, with invitations to either interview or call to learn more about the job. The callback rates for men and women were nearly the same.

A man’s GPA, low or high, didn’t make much difference. But among female applicants, the lowest-achieving group, with around a C-plus average, received the lowest rate of response (7.6 percent). Those with grades in the B-plus range had the best rate of response, around 17 percent.

Women with an A average got called back about 9 percent of the time, a significant drop-off. The difference was even more pronounced for women in math.

Then, Quadlin asked 261 hiring managers their opinions on fictional candidates based solely on their resumes. Employers were asked to rate on a scale of 0 to 11 whether they would be likely to interview a candidate, then to rate the candidates on competence, likeability, hard work, commitment and social skills.

Perceived traits that made men stand out were commitment and competence. Likeability was the only trait that gave women an edge.

The hiring managers, when asked open-ended questions about high-achieving female candidates, mentioned likeability 23 percent of the time, compared with 9 percent of the time for high-achieving men.

For example, one said: “Stephanie seems overconfident and very smart. She would be overqualified for any position in my company. Also, she doesn’t quite seem socially warm. Not sure why; there’s nothing wrong with being confident, but I get the feeling she’s arrogant.”

Quadlin added this disclaimer for women in college: Don’t feel pressured to play down success or restrain your potential. Grades are important for high-powered jobs or other education that comes later, such as law school or medical school.

“The types of employers who would hire a high-achieving woman are likely to be supportive of your career,” Quadlin said.