By Chisato Tanaka

Japan Times, Tokyo

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) The “Pet Loss Cafe” is the first place in Japan to offer a place for people who have lost their pets to gather and talk about their memories over a cup of coffee.

Tokyo

Ritsuko Shimazaki, 58, occasionally takes a 70-minute train ride to visit one coffee shop in particular near the upscale district of Omotesando in Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward.

The cafe — seemingly a standard trendy coffee shop with wooden tables and about a dozen seats surrounded by colorful flower bouquets — is the only public space where Shimazaki can cry over her lost dog without caring whether other customers stare at her.

Pet Loss Cafe is the first place in Japan to offer a place for people who have lost their pets to gather and talk about their memories over a cup of coffee.

Besides ordering drinks, customers fill out a form in which they answer questions regarding the type of animal they lost and whether they want to chat with members of the staff or be left alone.

Dearpet — Japan’s biggest manufacturer of items for pet altars — launched the cafe inside its headquarters after their staff felt the need for a place where customers could talk about their lost pets while looking around at the altar accessories in the shop.

“Many customers who came to buy altar accessories said they felt more at ease after talking about their loss with our staff.

However, often conversation had to be paused in the middle because staff have to attend to other customers. So, we decided to open a place where they can talk,” said Takeshi Nibe, the 48-year-old president of Dearpet.

Shimazaki, who lost her 16-year-old male Shih Tzu over a year ago, was the first customer when it opened in February.

“I wanted to show pictures (of my lost dog) and talk face-to-face with others. When I heard the cafe was opening, I was really excited to come,” said Shimazaki during an interview with The Japan Times at the cafe.

Shimazaki, a mother of two children, was in deep sorrow when her dog, Takeru, died of kidney failure and heart disease last March.

Although her husband and her children grieved as well, Shimazaki was the only one who could not get over the loss.

“During the first two to three months, I often cried in the bathroom alone. My eyes were swollen and an optic nerve was damaged due to too much crying. I had to keep seeing a doctor,” said Shimazaki. “I could not believe that this happened to me.”

Even after around eight months, Shimazaki still could not walk along the pathways where she used to stroll with Takeru every day, because she was afraid of encountering other dog owners who she used to talk with and being asked about what happened to Takeru.

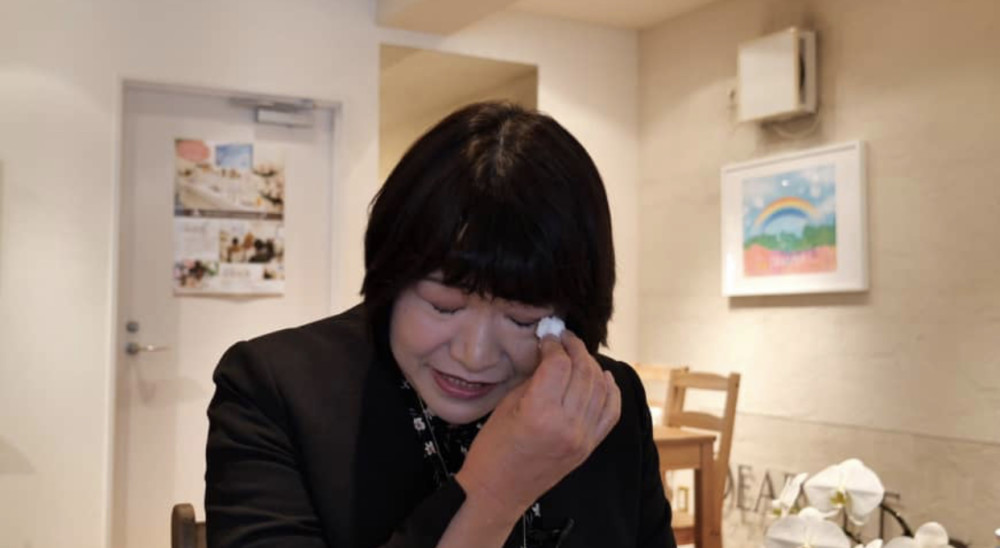

“Takeru used to hang out with a wild cat called Saba in the park we always stopped by, but since Takeru passed away, I could not even face Saba. I could not touch other pets either,” said Shimazaki while wiping away tears with a tissue offered by a cafe staff member.

Such symptoms seem to be quite common among people who have lost their pets.

According to a survey conducted last year by Ipet Insurance Co., which questioned 894 people who had lost their dogs or cats, more than half of those who had grieved over their pet said they were suddenly engulfed with sadness and could not stop crying.

With the number of dogs and cats being raised as pets exceeding the country’s total population of those under 15 years old — hitting over 18.55 million last year according to the Japan Pet Food Association — pet loss can be a big issue.

Megumi Kawasaki, who has been working as a pet loss counselor for more than a decade, said that most of her clients were women in their 40 and 50s who cared for their pets as a member of their family.

“In serious cases, some cannot leave their house for a year and consider ending their lives,” said Kawasaki. “(Losing pets) really is nothing different from losing your (human) loved ones, and sometimes it can be even worse for cat or dog owners who must face the sudden lack of a partner that used to stick with them all the time,” said Kawasaki.

Ekoin Temple in Tokyo’s Sumida Ward has a grave for dogs and cats. Ekoin Temple in Tokyo’s Sumida Ward has a grave for dogs and cats.

Dearpet’s Nibe said that while the idea of pets being part of the family is understood more widely nowadays, the situation was completely different when he established his company a decade ago.

When Nibe opened his altar accessory shop online in 2008, he received unexpected criticism for treating animals like human beings.

“In Buddhism, some monks teach that it’s not appropriate to hold a memorial service for four-legged animals, and that might have triggered the criticisms,” said Nibe.

In Buddhism, all living things are believed to circulate within six realms of existence — those of gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hell — and it has been widely understood among monks that animals, which are ranked lower than humans, have to be reborn as humans and train themselves to go to heaven, according to the book “Petto to Soshiki” (“Pets and Funerals”) written by journalist-turned-priest Hidenori Ukai.

This belief differs among various sects, however. Some sects, influenced by animism, believe that animals can go to heaven after they die.

The argument has been such a hot topic among monks that a religious newspaper, Chugai Nippoh, published a feature article with the title “Agree or Disagree: Can pets go to heaven?” in 2017.

The argument was even brought to court when the Tokyo Metropolitan Government ordered Ekoin Temple in Sumida Ward to pay property taxes on a location where pet remains were entombed, insisting that praying for dogs is not a religious activity. Locations for religious uses are exempt from tax.

Ekoin, which has held memorial services for animals since the Edo Period (1603-1868), won the case. The Tokyo High Court in 2008 said that the temple had provided memorial services for all living creatures, regardless of whether they were human or not, over a long period of time, following established religious rituals.

Shokei Honda, vice chief priest of Ekoin Temple, insisted that animals can go to heaven. “Animals have life and so do we. And we, human beings, have biased eyes and because of that we might consider them (animals) different from us. From Buddha’s point of view, the lives of animals and human beings are equal.”

At Dearpet, a monk who believes that animals can go to heaven holds a monthly commemoration ceremony.

Shimazaki, who held a one-year commemoration for her dog at Dearpet in March, said that she still misses her dog Takeru.

“More than a year has passed, but I still cannot get over it,” said Shimazaki with her eyes welling up. “I wonder if I can keep living like this.”