By Felicia Browne

Caribbean News Now, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands.

A few weeks ago, a friend shared the good news of getting a new job. She was very excited by the idea of working with a high-end organization and making a good salary. As I congratulated her, I couldn’t help but reflect on the fact that my friend would likely face economic inequities in women’s rights, inequities found throughout the Caribbean that are often ignored and unchallenged.

For instance, although many countries have engaged in national debates about the establishment of a minimum wage, very few have seen the urgency of implementing one. This is discouraging given the fact that women and their children remain the poorest population in the Caribbean, that there is very limited public assistance and free, basic health care available, and that the cost of living is ever rising.

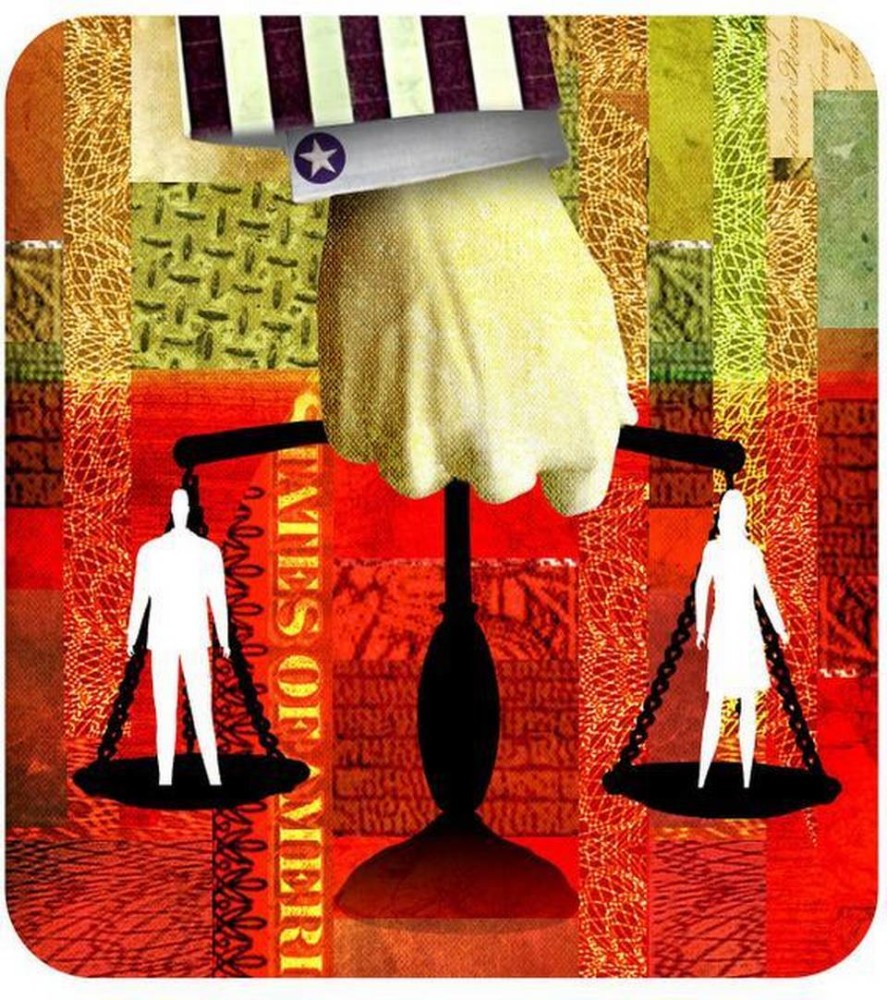

Beyond the need for a living minimum wage and necessary associated benefits, the systemic inequity that women typically earn significantly less than men for comparable work should be addressed so that women receive equal pay for equal work.

Internationally the median earnings of full-time female workers are 77 percent of those of full-time male workers. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) claimed in 2012 that for “professional” jobs in the Caribbean region, (including those related to the higher paying jobs in architecture, law and engineering) the wage gap between men and women was significantly higher.

Caribbean women earn 58 percent of men on average in comparable professional positions, even though Caribbean women have exceeded men in higher education. Due to discrimination and cultural prejudices, they often pursue careers in psychology, teaching or nursing, professions that perpetuate the traditional role of women as nurturers and caretakers.

Countries which have taken steps towards employment rights by increasing the wages of women and other workers have generally improved the standard of living and quality of life for women and their families. However, the minimum wage should be high enough to allow women to provide adequately for themselves and their dependents.

Women as a minority group are at a further disadvantage as many women are employed part-time and subsequently ineligible for benefits, such as health insurance (IDB, 2012). These types of employment discrimination contribute to women’s inability to provide sufficient health care and financial security for their dependents.

Employment rights’ advocates have long held that although women have continued to make strides in the economic development of their countries as workers, many are greatly disadvantaged due to a lack of educational opportunities and effective legislation for women in the workforce. Laws are needed to protect women from sexual harassment, to provide them affordable child care services, and to ensure them proper security and transportation, especially those who work late-night and graveyard shifts.

A larger percentage of women tend to be active in high income countries, where over two-thirds of the female adult population participate in the labour market and the gender gap regarding participation rates is less than 15 percent. This is especially true in countries with extensive social protection coverage and societies where part-time work is possible and accepted.

Education, especially higher education, has not only allowed women to re-define their place within the workplace, but has been a major factor in improving their standard of living and quality of life. In providing these educational opportunities for women, developing countries have seen women’s contribution to national economic prosperity.

In order to close the gender gap, advocates have recommended that employment reform for women should seek to provide a more equitable work space and equal maternity leave for both parents. This could help level the playing field with respect to decisions about hiring women and men. Furthermore, it could encourage men and women to dedicate more time to their newborns, generating more equal decisions.

It is significant that the World Bank defines employment as covering certain types of non-market production (unpaid work), including production of goods for one’s own use. Unfortunately, the World Bank and other international agencies continue to exclude household work in one’s own home, such as cooking, cleaning, shopping, washing ironing, etc, and child, spousal and elder care, each of which involve a very large range of skills and responsibilities.

Women’s work as wives, mothers, caretakers, and homemakers are essential and equal contributors to the society and economy, however no monetary value is acknowledged or assigned to their work by society or the law. To continue to devalue women’s work in the home as an obligation with little or no financial compensation remains the greatest discrimination against women.