By Carrie Wells

The Baltimore Sun.

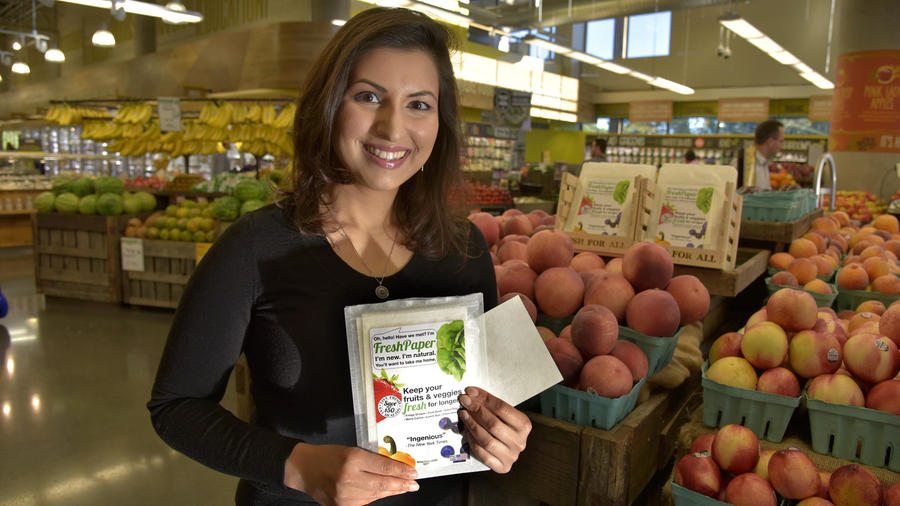

Ellicott City native Kavita Shukla’s business started with a trip to India and a middle school science project.

The 30-year-old entrepreneur was 12 when she visited her grandmother in India and accidentally swallowed some water while brushing her teeth. She worried she would become ill, but her grandmother brewed her a spice tea as a home remedy.

“I drank it, and I never got sick the rest of my time there, and that moment sparked my curiosity,” Shukla said. “I couldn’t believe that my grandmother had created something that to me seemed almost magical.”

The antimicrobial qualities of the tea became the basis of a science project that eventually evolved into a product called FreshPaper that Shukla said keeps produce fresh for two to four times longer than usual. The sheets of paper, infused with the same spices in her grandmother’s tea, can be slipped in a carton of berries or a produce drawer and last for a month. It works by keeping in check the bacteria that causes fresh foods to rot.

She won’t disclose the exact spices, but said her company’s name, Fenugreen, is a play on the spice fenugreek, a traditional ingredient in Asian and European cooking that is sometimes used as a folk remedy for diabetes and to increase lactation in breastfeeding mothers.

FreshPaper is now carried by retailers such as Whole Foods, Bed Bath and Beyond, and Ace Hardware. On Amazon.com, FreshPaper has an 80 percent 5-star rating. A supply of about 8 sheets retails for about $9.99.

The business of fresh appears to be booming, and Shukla and her product have made apperances on “The Today Show” and “Dr. Oz.” But she would not disclose sales or how many people Fenugreen employs. In addition to the Columbia headquarters, she said, there are production facilities in Baltimore and at an undisclosed Midwestern location.

Fenugreen is also one of 10 finalists in a contest sponsored by Intuit QuickBooks to win a coveted Super Bowl ad spot.

Shukla, who is passionate about reducing global food waste and originally tried to start her company as a nonprofit, is now exploring how to get FreshPaper into the hands of more people in developing countries who don’t have access to refrigeration.

“Bringing it to market was a big step toward getting it to people in need,” she said.

After returning home from her trip to India, the Burleigh Manor Middle School student began a science fair experiment with the spices her grandmother brewed in the tea, dipping moldy strawberries into a watery infusion. She said the technique worked but seemed somewhat impractical.

Later, at Centennial High School, Shukla said she infused the spices into paper and received a patent for the product at age 17. As an economics major at Harvard University, she tried to launch a nonprofit to distribute the FreshPaper in developing countries but was discouraged by some who told her building such an enterprise would be too difficult. She abandoned the effort for a while.

In the summer of 2011, still living in Cambridge, Mass., she partnered with a friend, Swaroop Samant, and took a bundle of sheets of FreshPaper made in her apartment by hand for a few hundred dollars to a local farmers’ market. The product was a hit, she said, both among farmers who didn’t want their produce to spoil and among shoppers.

“By the end of the summer, we were selling hundreds of packs,” said Samant. “We were really floored.”

Samant, who co-founded Fenugreen, graduated from medical school at the Johns Hopkins University, and while he was training there, he encountered a lot of diet-based illnesses like cardiovascular disease or diabetes. The idea of a product that could help consumers eat more fruits and vegetables because they would stay fresh longer struck him.

A year later, a Whole Foods buyer who heard about the popular product called, asking to meet with Shukla and Samant to discuss it. Samant said the company at that point consisted of the two of them and an intern. So all three went to the meeting with the buyer.

“We thought if we brought everyone in, we would seem bigger and they would give us a chance,” Samant said.

Whole Foods signed on and suddenly the fledgling company — still making the papers by hand — was faced with what seemed like a huge order, about a case for each of the several hundred Whole Foods stores in the U.S., Samant recalled. They made their first delivery to Whole Foods in a borrowed Toyota Corolla.

“We very quickly realized, when you start something as a hobby and it turns into something bigger than you imagined, as you go up in scale it’s like you’re building the company anew each time,” he said.

The product seems a natural fit for an organic and fresh foods retailer like Whole Foods. Matt Lamoreaux, the produce coordinator for the Whole Foods Market Mid-Atlantic region, said the company also tries to support small businesses like Fenugreen.

“This is a unique product for our produce department, and it’s always a goal to help small businesses that want to grow,” he said.

Shukla and Samant relocated the business to Columbia in 2013 as they expanded.

An estimated 30 percent to 40 percent of food in the United States is thrown away, said Brian Lipinski, an associate with the Washington-based World Resources Institute think tank. The United Nations estimates that 1.3 billion tons of food is wasted worldwide each year.

In the U.S., most of the food thrown away is from grocery stores, restaurants and by consumers at home, Lipinski said. At the agricultural level, there is also waste, but items like bruised apples may get used for other products, he said.

Much of the waste at the grocery store level may be due to consumer expectations, he said.

“If I go to a grocery store and there’s only five apples left, I’m going to assume that those are the bad apples,” Lipinski said. “It’s always better for a grocery store to have too much of something than not enough.”

In a restaurant, diners may opt not to take home a small amount of leftovers, and at home, consumers may buy vegetables with the intention of cooking them but not get around to it in time.

“You might say, ‘This is the week that I’m going to learn to cook kohlrabi,’ and then you don’t cook it,” he said.

While the typical consumer can’t do much about food waste in grocery stores or elsewhere, FreshPaper could empower consumers to do what they can, Lipinski said.

“While we can agree that food waste is bad, it can be hard to take action,” he said.

Shukla, meanwhile, hasn’t given up on her original vision for the product, remaining passionate about reducing food waste, particularly in developing countries.

She said she’s pursuing partnerships with nonprofits and other nongovernmental organizations to distribute FreshPaper internationally. It’s already distributed in some communities in Malawi and Haiti that do not have refrigeration, she said.

“For such a long time, I thought it would not be enough to get my idea out in the world,” she said. “Sometimes it’s about taking the first step. For me, taking it to the farmers’ market was what changed everything.”