By Kurt Christian

Herald-Times, Bloomington, Ind.

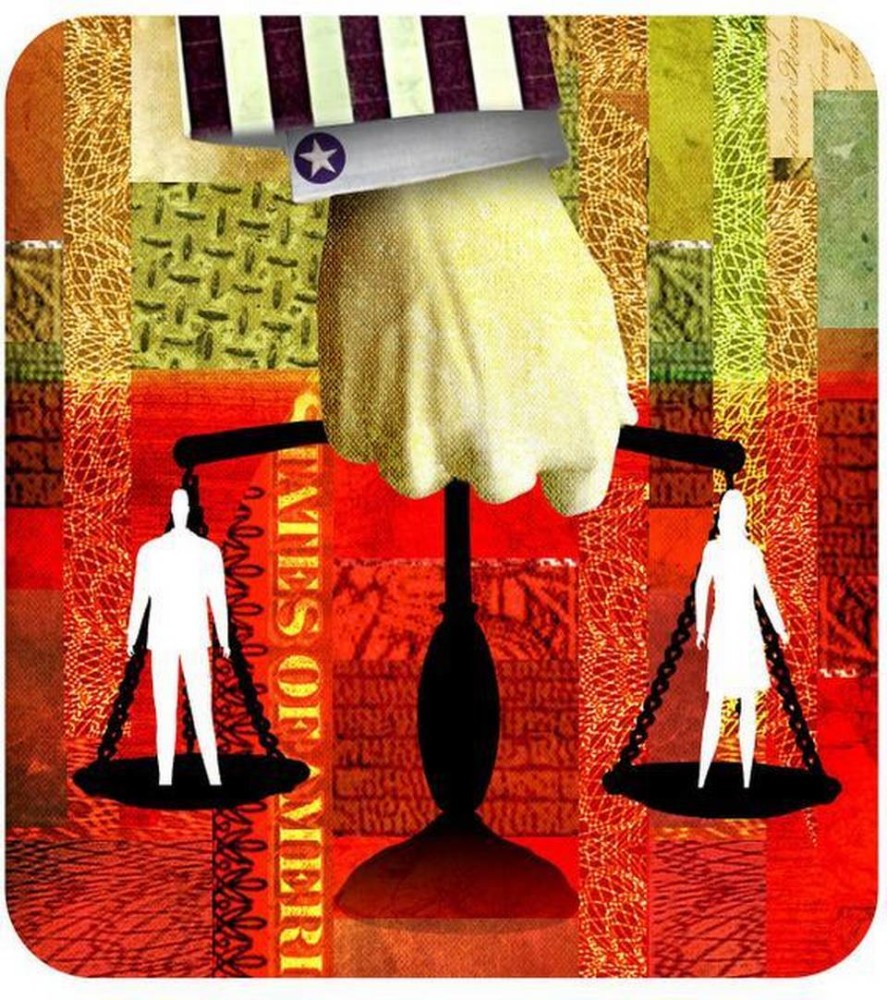

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) When it comes to women and money the unfortunate truth is that men and women are paid differently for the same work. Empirical data from the U.S. Census Bureau states that for every dollar a man makes, a woman will earn 79 cents.

Herald-Times, Bloomington, Ind.

Pay day. The culmination of a week’s hard work. Something all employees look forward to, though some at a lower rate than others.

Men and women are paid differently for the same work. Empirical data from the U.S. Census Bureau states that for every dollar a man makes, a woman will earn 79 cents.

What remains uncertain is a divide within that 21-cent gap. Though about 13 cents are purportedly accounted for, there’s an almost 8-cent deficit for women that some attribute — at least partially — to systemic gender discrimination.

“It’s pretty rare to find someone that finds it unfair to pay women as much as men,” said Vicki Shabo, vice president of the National Partnership for Women and Families. “But this is something that can’t be seen.”

The data were highlighted in a report released this month by the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress.

Where pennies slip through the cracks

According to a study titled “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations,” 62 percent of the wage gap can be attributed to variances across industries, education and experience, race, region and even factors such as unionization.

The reason for the remaining 38 percent isn’t as plainly stated, and opinions differ on whether individual biases, managerial approaches, categorical behavior differences or gender discrimination are to blame.

“There’s compelling empirical research that shows this is straightforward discrimination,” said Cate Taylor, an assistant professor of sociology and gender studies at Indiana University. “We have such good data on workforce characteristics and what kind of people do what kind of jobs — that’s why they say the (unexplained portion) must be due to discrimination. There’s nothing else that can fit into the model.”

Taylor also cited experimental evidence in which subjects were asked to determine what wages they would give to a person based off a resume. When presented with a list of workplace-related attributes, both male and female subjects approved higher wage rates for “John” than they did for “Jane.” For both instances, the candidate’s qualifications remained constant.

“This discrimination is not conscious and it’s not malicious,” Taylor said. “There are unconscious ideas of what men and women are good at, and we tend to pay people more when we think they’re good at something. Put that together with studies that show the national data sets can’t explain the whole of the wage gap, and I think that’s fairly irrefutable evidence.”

Taylor said though most discrimination made within that uncertain 38 percent might be done on an individual level, gender discrimination takes place on a much broader scale. Today’s culture devalues the jobs women work in, she said. It’s why workers in child care and other historically woman-dominated fields make so little. Taylor also noted the shifting demographics of the computer science industry. When an industry dominated by women was no longer seen as secretarial work and men began dominating the field, pay rates shifted to match the changing culture.

“Studies find that, as women go into ‘men’s jobs,’ they get paid less,” Taylor said. “When occupations change their sex composition, they change how they pay. It’s not one person that doesn’t like women; it’s as a culture, once a woman starts doing a job, we start paying them less.”

Pay in the next cubicle

In Indiana, women are paid at an even greater disadvantage for the same work as their male coworkers; 25 cents less per dollar.

According to U.S. Census data for men and women that work comparable full-time jobs, that amounts to an annual wage gap of $11,427 a year. That can be translated into 86 more weeks of food for a family, 11 more months of mortgage and utilities payments or more than 15 additional months of rent, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families.

All nine of Indiana’s congressional districts reported inequalities between men and women in 2014, and in Bloomington’s 9th District, a man’s median annual wage was found to be $46,054, while his female counterpart was paid $34,954. That means that a woman in Bloomington earned approximately 76 cents for every dollar her male coworker made.

Despite that difference, Bloomington Human Rights Commission director Barbara McKinney said she hasn’t seen a case cross her desk alleging a wage gap due to gender discrimination in her 27 years at the organization. If McKinney were to see such a case, she said, it would be the commission’s job to investigate the incident to determine whether the wage gap was a result of gender discrimination. If the commission were to find wrongdoing, a settlement between the parties would be sought before the case could proceed to court.

“The question can get murky when the jobs are similar but not exactly the same. We would look at the employer’s explanation, we’d look at the job duties, we’d look at the payroll records to see if the women were paid the same amount that a man in question was paid,” she said, outlining just how an instance of discrimination is determined.

The fight for fair pay is especially relevant today, on 2016’s Equal Pay Day. Today symbolically marks the point at which an average woman’s wages would catch up to her male counterpart’s earnings from the previous year. The designation is just one element of a greater effort to bring the wage gap to the forefront of the nation’s attention that has been culminating since as early as the 1960s, according to Taylor.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, women have seen a narrowing disparity between their annual median wages and their male counterparts’ between 1963 (59 percent) and 2014 (79 percent). Although the trends describe a shrinking gap, at the current rate of change, that gap will not close until 2059, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Taylor voiced skepticism of that projected resolution date barring significant changes within the workplace.

Fair pay solutions

Hoosier women lose more than $10 billion in wages to the pay gap each year, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families. The organization further suggests minorities and aging women earn disproportionate pay. For women in the state who hold full-time, year-round jobs, African-American women are paid 66 cents, Latinas are paid 54 cents and Asian women are paid 77 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men.

This month’s report also stated that “while women ages 18 to 24 earn 88 percent of what their male counterparts earn, women over age 35 earn only 76 percent.”

Census information highlights the impact those statistics may have on Indiana — a state that has more than 317,000 family households headed by women — and the nation, where mothers are the primary or sole breadwinners in nearly 40 percent of families. Shabo praised efforts made by companies such as The Gap and Salesforce, where internal audits have been made to not only track, but address wage gaps.

In addition to tracking disparity and holding key policymakers accountable for enforcing fair pay, Taylor noted workplaces that are results-oriented have succeeded at retaining women in higher positions. These company-level policies, combined with national regulation efforts, may provide solutions. The Paycheck Fairness Act, supported by the National Partnership for Women and Families, is currently before Congress. The legislation’s goals are to close loopholes in the 1963 Equal Pay Act, help to break patterns of pay discrimination and establish stronger workplace protections for women.

“The reason why legal tools are needed is so that, once somebody believes that they are paid unfairly, they have stronger tools to support their case. They can prove that any differentials that exist are actual, legitimate, bona fide reasons for being paid differently,” Shabo said. “Ultimately, it shouldn’t matter where you live or work — everybody needs access to basic tools that help them be paid fairly.”