By John Schmid

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) 18-year-old Zeynab Ali is a senior at Milwaukee’s Rufus King High School. In between applications to college, she just self-published a book meant to add her voice to one of the nation’s most complicated political issues, immigration.

MILWAUKEE

At a time when the United Nations says the world has never seen so many refugees, with tens of millions displaced by war and persecution, Milwaukee teenager Zeynab Ali is just one more.

Born in a refugee tent village in Kenya to parents forced to flee the Somali civil war, Ali landed in the United States when she was 6. She’s been watching an anti-immigration backlash take hold in one western nation after another. But what Ali and her family witnessed on their odyssey, starvation, anarchy, mindless killings, are facets that don’t always make their way into the emotionally charged debate on immigration.

“Some people don’t understand the sacrifices that immigrants make,” she said.

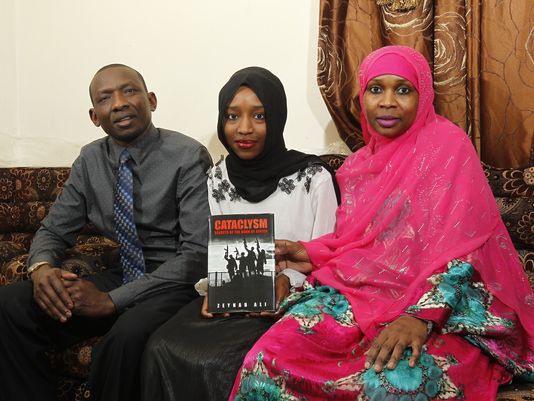

The 18-year-old senior at Rufus King High School, in between applications to college, just self-published a book meant to add her voice to one of the nation’s most complicated political issues.

“Cataclysm: Secrets of the Horn of Africa” is part history of Somalia and part personal memoir. And because Ali’s story involves one of the world’s most “unstable and dangerous” nations, in the words of a U.S. State Department travel warning, her book deals with the traumatic extremes of the modern refugee experience.

Ali’s chapters on Somali history are written in a matter-of-fact style, beginning with European colonialism and spanning national independence in 1960 and the famine and political chaos that followed.

The personal narratives, however, are anything but academic. They begin with firsthand accounts Ali learned from her parents, whose educations didn’t even include grade school because Somali warlords destroyed schools along with the economy.

She describes the murder of her mother’s father, which took place in front of her young mother, at the hands of bloodthirsty bandits who pillaged and raped in the Somali villages.

Post-traumatic anxiety is common for political refugees, Ali said, citing her research and personal experience. Her father witnessed his share of bloodshed and used to scream in his sleep.

Ali describes her childhood in the refugee camps across the border in Kenya, including the time a scorpion bit her and made her sick with hallucinations. Food and civility were in short supply. She often didn’t see her parents, who worked long hours for pocket change, but lauds them for their values.

And she describes her family’s integration into the U.S.

Ali’s own English is flawless even though it’s not her native tongue. Her parents, who barely speak rudimentary English, hold together a family of eight children by working menial jobs. She’ll be the first in her family to go to college.

In an interview, Ali said money couldn’t be tighter at home, but her parents continue to send a portion of their income back home to surviving relatives in Somalia.

Social conditions in Milwaukee, the nation’s third most impoverished city, in some ways remind Ali of the world she fled.

“The poverty rate in Milwaukee and obviously the violence are similar,” differing, of course, in degree and extremity, she said.

It’s because she doesn’t want to see her adoptive city slide further into urban distress that she has become an anti-crime activist in her spare time, Ali said.

Even without the book, she’s well known to civic leaders and law enforcement agencies. She’s active in Safe & Sound, a crime-prevention nonprofit that acts as a liaison between urban residents and a gamut of law enforcement agencies, building a crucial bridge at a time of heightened distrust of police. A year ago, Safe & Sound honored Ali with its annual “Youth Leader Award.”

Five weeks ago, the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee awarded Ali its “Young Adult Leadership” award, recognizing her participation with multiple community groups, including co-founding and chairing Inspirational Impact, an organization that tackles human trafficking, a criminal practice of conning and coercing young people into prostitution. “The average age of a human trafficking victim is 12 to 14,” she said.

“Zeynab is a true inspiration and role model for all,” said Safe & Sound Executive Director Katie Sanders, who admires Ali’s “incredible community leadership, activism and involvement in social issues.”

Ali reflects another attribute of modern immigrants, as evidenced by statistics: “Immigrants are twice as likely to become entrepreneurs as native-born Americans,” according to the Kauffman Foundation. And Ali displays her share of entrepreneurial zeal.

While most upward-bound high school seniors are content to complete major term papers, Ali’s book was entirely extracurricular.

As digital change lowered the barriers in the once-elite world of book publishing, she opted to self-publish rather than submit her work to established imprints.

As of last month, her book has been available in hardcover, paperback and e-book via online vendors such as Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Under the rules of self-publishing, she needed to pay publishing house Xlibris, so she crowd-sourced as much as she could. Her parents pitched in a few hundred hard-earned dollars to make up the difference.

The topic of Ali’s book couldn’t be more timely. “We are now witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record,” according to the U.N. Refugee Agency. What’s more, Somalia is one of only three nations that produced more than half of all the world’s political refugees, the other two are Syria and Afghanistan, the agency found. Over half the world’s refugees are children.

“Not many people know there are refugees in the city, Burmese, Arab, Hmong and some African,” Ali said of Milwaukee.

The U.S. found itself ensnared in Somalia in the 1990s, leading a peacekeeping mission that degenerated into the bloody 1993 Battle of Mogadishu. The U.S. no longer stations diplomats in Somalia and warns Americans to stay away because of “kidnapping, bombings, murder, illegal roadblocks, banditry and other violent incidents.”

Syria and its civilian slaughter and precarious boatloads of desperate migrants have drawn the most attention to the world’s refugee crisis. But it was Warsan Shire, another young Kenyan-born Somali refugee woman, who wrote what many consider the global anthem of the humanitarian refugee crisis. The lines appear in Shire’s ironically titled poem called “Home:”

“You have to understand That no one puts their children in a boat Unless the water is safer than the land”