By Bill Swindell

The Press Democrat, Santa Rosa, Calif.

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Tech innovator Tim O’Reilly has written a book entitled: “WTF? What’s the Future and Why It’s Up to Us.” O’Reilly says he doesn’t fear the future. He writes: “Instead of using technology to replace people, we can use it to augment them so they can do things that were previously impossible.”

The Press Democrat, Santa Rosa, Calif.

Tim O’Reilly, evangelist for the digital era, has been described as a web guru and an internet pioneer.

He’s popularized trailblazing concepts such as open source software and Web 2.0, the era that followed the bursting of the dot-com bubble, and ushered in user-generated content and social media.

He’s done it all from his perch as the founder of Sebastopol-based O’Reilly Media, a technical book publishing company that has morphed into an online learning platform and events business — adapting itself to the disruptive changes brought on by a digital world. The company employs around 400 people with offices in Boston; Farnham, England; Oakville, Ontario; Beijing and Tokyo.

Now O’Reilly, 63, is turning to a much broader general audience with his latest project, a book entitled: “WTF? What’s the Future and Why It’s Up to Us.”

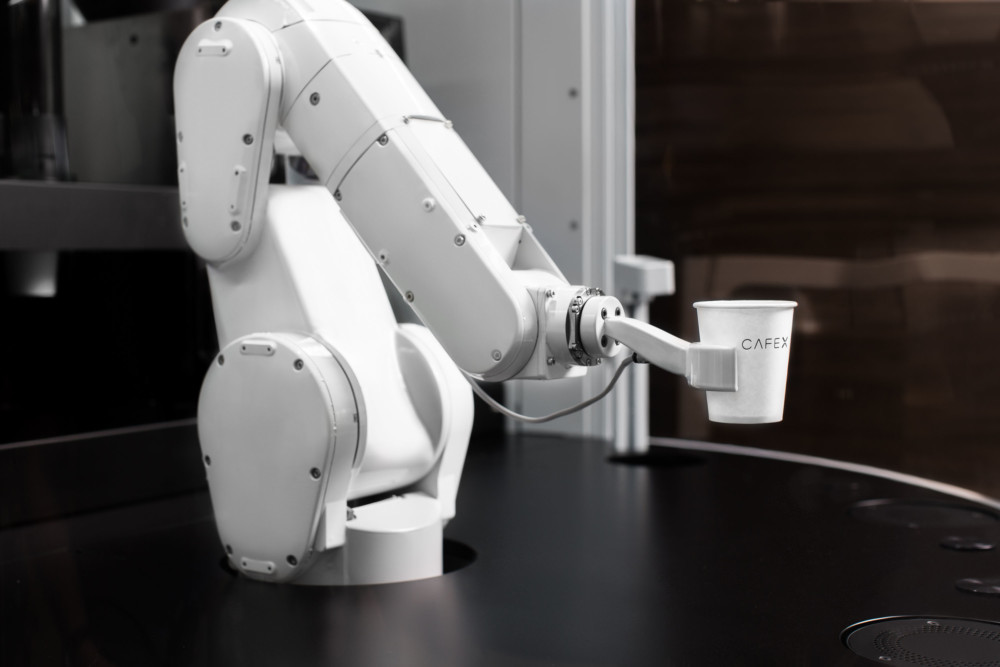

In it, he takes what he has learned from some 40 years in the tech world and applies it to the challenges facing our economy and society, where artificial intelligence, robots and big data are changing our lives.

O’Reilly doesn’t fear the future. He writes: “Instead of using technology to replace people, we can use it to augment them so they can do things that were previously impossible.”

In an interview at his Oakland home, O’Reilly covered a wide range of topics: his business, weaning ourselves from Wall Street’s influence on our economy, sexism in the tech culture, and why he thinks ride-hailing business Uber has been over-hyped. The transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: You are more bullish on artificial intelligence (AI), robots and big data transforming our economy than some others. Why is that?

A: I don’t know if everybody is bearish. There is a wide range, from people who are very worried to people who aren’t.

I am actually bearish for the prospects of our economy in a way a lot of people aren’t. I think we are thinking about AI wrong. We are living in a giant robot already. How do you find out about things? Through Google, through Facebook, through Twitter. There are these vast systems that combine algorithms and people. In some sense we are living in the AI, and it’s a prototype AI… Right now I’m optimistic about the subject of jobs. What I’m not optimistic about are the moral values of business.

You realize that our financial markets also are in an algorithmic system with an objective function, which is to maximize shareholder value. We actually just created our own rogue AI. The reason it is the most important one is because Google and Facebook and all the other AIs are answerable to it. That’s why in some sense the financial markets are the master AI.

Q: Let’s look at the role of financialization, for example, at Uber. Its current market value of $50 billion appears to be derived from future services years down the road such as driverless cars and transporting in the wholesale market. But you are a skeptic.

A: I spend a lot of time on Uber in the book. If you actually understand the business model of Uber and Lyft, you realize how fatuous much of the analysis is of the impact of driverless cars on these platforms.

Why have they been able to be so much more effective than taxi cabs? The reason is they are using part-time drivers supplying their own cars, which means the number of cars they have scales automatically to meet demand. When there’s a lot of demand, there are many more cars. When there is not much demand, there are fewer cars.

Their expenses go up and down. Now imagine they have all autonomous cars on the road. They have to have enough cars to meet that peak demand. You see these statements that they won’t have to pay drivers anymore and the cars will be fully utilized.

No, the cars will be very lightly utilized because they have to have enough cars for peak demand. It only works if those autonomous cars belong to someone else who will take on that risk. If they put the cars on their balance sheet, they are going to have lower utilization, they are going to have all the costs, and the business will be actually worse.

Q: Your thesis is that it’s not the technology, but the choices we make with the technology?

A: Ultimately, we have moral choices. We make choices on how to deploy technology. The way we got out of the dark days of the industrial revolution was by making forward-thinking choices for people. We reduced working hours. We sent kids to school instead of the factory. In 1909, only 9 percent of eligible-age youth in the country went to high school. Twenty-five years later, it was up to 70 percent.

We kind of got into this idea that technology and the destruction of jobs is inevitable. It’s not at all. It’s a series of choices we are making. What is leading us to make these wrong choices? You look at a company like Apple making more money than any company in history and somehow they still think they need to make their products in China … in factories where people are driven so hard they commit suicide.

Q: But Wall Street would throw a fit.

A: So what if Wall Street would throw a fit?! You may get a bunch of shareholders who will throw out the management. We have allowed one set of parties in our economy to basically loot the economy. This is a multiparty system. Why is it somehow that it all belongs to the shareholders?

This is a pernicious idea that got planted in the 1970s and it has wrecked our economy. Coming back to AI, this has been the master algorithm of our society. We have basically been telling companies to optimize for the wrong thing.

All the fears of AI have been basically coded into our economy. That’s the AI that I am afraid of.

Q: What’s a company that strikes the right balance between growth and providing value to customers and workers?

A: You can build companies outside the system. You look at a company like REI (the member-owned cooperative that sells outdoors equipment). They are actually more successful than their competitors. They have better same-store sales. Better sales in growth. But they give most of the profits back to members in the form of dividends to members instead of financiers.

They are not playing in that system. Same thing with the Green Bay Packers. They are owned by the fans and sold themselves to their ticket-season holders. And they use that funding to keep their prices low. I won’t argue that we have not produced enormous value for the world through this financial system, but it goes wrong. We are just due for another correction.

Q: What about the workers who will be harder to retrain in this new economy, like the 50-year-old factory worker in the Midwest without a college degree? How can the future be hopeful for him or her when their replacement jobs will be for less money and benefits? President Trump’s message of economic nationalism resonated with a lot of them, such as those at Carrier Corp., which announced a major layoff at its Indiana plant in February 2016 — an action that helped fuel his successful presidential bid.

A: I did some back-of-the-napkin math on closing that Carrier factory. Sending that factory to Mexico might save $50 million to $70 million a year, which is a lot of money. But United Technologies, the parent company of Carrier, spent $12 billion in that same year on stock buybacks. They have $12 billion to prop up their stock, and they don’t have $50 to $70 million to pay people? What are the incentives in our system that are telling companies to get rid of people, don’t pay them enough to live on, keep your costs as low as possible even if it means throwing people out of work? We are living in an AI that is hostile to humanity.

It’s fundamentally a political act. We have to rewrite the rules.

Q: How has O’Reilly Media changed in a digital world from its roots as a book publisher?

A: We have adapted. Publishing is about 20 percent. Events is about 30 percent and 50 percent is our online learning platform, Safari Books Online.

What we realized early on is we weren’t really a publisher. Our fundamental business is changing the world by spreading the knowledge of innovators. How do we get information about emerging technology from people who are developing it to people who follow and learn from it? We can do that in lots of different ways.

We dipped our toe in advertising. Advertising rewards the trivial and the salacious. And that’s not us. We focused in on businesses where people pay you for valued delivery.

Q: Recent headlines have shined a spotlight on the widespread sexism in tech at such places as Uber and Google as well as venture capital firms. How truly bad is it, especially regarding the promotion of women?

A: I would have to say Silicon Valley gets a C-minus or D-plus on women. Some companies are very different. I look at my management team at O’Reilly, the top management is probably 60 percent women. Laura Baldwin, president and CEO, runs the company day to day.

I once had an interesting conversation with somebody senior at the Obama White House who had previously worked at Google. She said until she went to the White House, she didn’t realize how unfriendly to women Google was. She said you weren’t invited to certain things. It was just the “who was in and who was out?”

I think there is a long way to go. Of course, the venture capital industry is terrible.

Q: What are the responsibilities of large companies such as Facebook and Uber given their market dominance?

A: There is only a small number of companies that are going to become scalable at the level of Facebook. Twitter is subscale. Snap is probably subscale. If there are a limited number of these companies and they are going to be these semi-monopolistic platforms, they have to become the scaffolding for an economy of smaller businesses.

What I really want people to take away from the book — especially those who are at these companies — is that they have an obligation and a self-interest to build a robust platform. Uber and Lyft have an obligation to make it good for their drivers, not to get rid of them. Airbnb has an obligation to make it good for their hosts. Have the economy of Airbnb get better for these people.

Q: Did you draw on lessons from O’Reilly?

A: We saw that publishing was being less lucrative. We said: ‘What does this mean for our authors?’ People got two things from books: royalties and validation in their careers. Part of what we did with our events business is give people other venues to become celebrities, to build their brand. On the Safari platform, we worked very hard to come up with new kinds of economic models. We added live online training. It’s a way to pay our talent. Customers love it, but we can also build a viable, sustainable model.

Q: What’s next for O’Reilly Media?

A: We have really decided that the platform, Safari, is the heart of our business. All of the parts of our business are trying to feed into that. The video from the events would show up in Safari. Let’s start doing live training. Let’s get these people who do these talks at conferences on the platform with interactive training.

We also are thinking about how do we integrate the sponsorship model for events into the platform? The biggest differentiator in a lot of ways from so much that is happening in Silicon Valley is that we are basically focused on being a real business that makes money. We will take that over fake growth.

Q: What role will the changing nature of education play in the future?

A: We are moving from a world where people study for something, have a job, and then be done to one in which people need to continuously educate and re-educate themselves.

O’Reilly Media is a learning company for the next economy. Customers are subscribing to Safari and taking training because they are trying to educate themselves.

We are also an investor in an open-access science journal, as science is a big part of the cutting edge in new fields. Every company has to become a source of continuing learning for its employees. It has to invest in its employees. We have this crazy idea that the market should just spit out people with all these appropriate skills.