By Christen A. Johnson

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Columnist Christen Johnson likens Tiffany Haddish’s debut memoir, “The Last Black Unicorn,” to a juicy brunch session with one of your closest girlfriends who is giving spare-no-detail recaps of her jaw-dropping, eye-bugging escapades.

Chicago Tribune

You may know Tiffany Haddish as the goofy girl from the Groupon Super Bowl commercials, or as the free-spirited, breakout star of last summer’s blockbuster, “Girls Trip.” You may have even doubled-over laughing from one of her stand-up bits at a club or arena.

Whatever way you’ve experienced the actress and comedian, you know she is consistently illuminating, always serving candor, effervescence and just plain fun, with splashes of raunchiness everywhere in between.

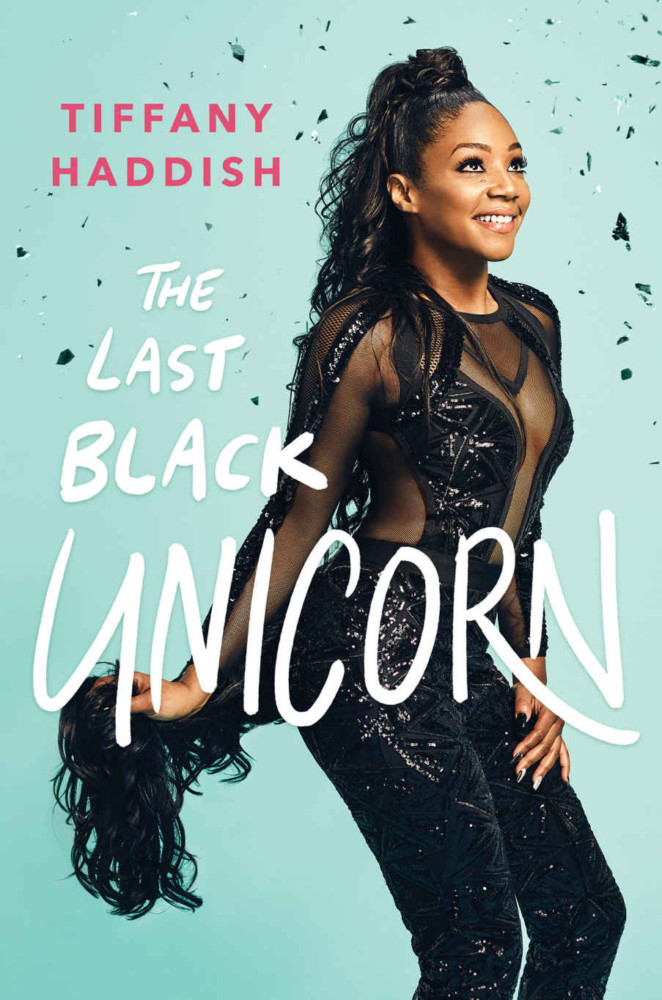

Her debut memoir, “The Last Black Unicorn,” does nothing less. Turning the pages is like leaning in during a juicy brunch session with one of your closest girlfriends who is giving spare-no-detail recaps of her jaw-dropping, eye-bugging escapades.

Much like many of the roles we’ve seen her in, Haddish is raw and uninhibited as she details the delicate balance of learning her worth while remaining unwavering in who she is already.

She unashamedly takes us through the nuances of her upbringing and familial woes, early talents and interests, former love life and sexual encounters, and her meteoric rise in the comedy industry and Hollywood.

The memoir starts as a nonlinear coming-of-age tale that, when simplified, can feel as if the facts are not in Haddish’s favor: She’s poor, illiterate until ninth grade, and in the foster care system despite being in her grandmother’s custody. Her mother is in a mental-health facility, and her father abandoned her when she was 3 years old.

This is where Haddish’s persistence shines; she is determined to not fall victim to her circumstances, even though she didn’t necessarily view her circumstances as challenges.

She writes about using humor to find creative loopholes for her illiteracy, before learning to read in just one month; capitalizing on an extracurricular activity in high school, making $50 a game for being the team mascot; and persuading a family court judge to sign a media release form, giving her permission to be in a news special while at the Laugh Factory comedy camp.

In her young adulthood, we see Haddish yearn for love and to be loved, fully and faithfully. One of her most gut-busting, yet heart-wrenching, accounts is her detailed revenge on her cheating, wanna-be pimp, ex-boyfriend, Titus.

As crude as the vengeance was, it feels justified, especially after walking through Haddish’s heartbreak.

Continuing on her love quest, Haddish processes a slew of relationships, one with a special needs co-worker, Roscoe, another with an abusive ex-husband she divorced, then remarried.

She acknowledges that these experiences are “unbelievable,” and that they will “either make you cry or laugh.”

But, somehow, with her colloquial style, uncensored retorts, and personal encounters recounted as scriptlike dialogue, Haddish does make you laugh, but also makes you relate and empathize, to her pain and joy, her embarrassment and excitement, her boldness and fear, and everything else in between, as any great comedian does.

You can’t help but root for her while laughing out loud at her antics.

On her climb to stardom, Haddish earned her comedy stripes amid rampant sexism, saying, “I can’t tell you how many (promoters) tried to tell me that to get onstage I had to get on my back.” Even her peers would deny her talent, saying, “unless you opening up those legs, you can’t go (on tour with me).”

Now, she writes, the men who challenged and minimized Haddish are the same ones asking her to headline shows for sold-out arenas.

In the words of her “comedy guardian angel,” Kevin Hart, Haddish is undeniably “a force” that “demands to be heard and respected,”, as a comedian, but also as a woman secure in the truth of her story.

Despite societal forces that make it difficult for black women to be viewed as multilayered and complex, “The Last Black Unicorn,” with its gutsy vulnerability and acute self-awareness, offers a space for black women to be just that.