By Alison Bowen

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr)> Despite health and government officials’ recommendations that sexual assault patients be treated by nurses trained to recognize trauma and collect evidence, many nurses receive no such training.

CHICAGO

When she woke up, she was naked in a stranger’s apartment. Her body numb, she didn’t know how she’d gotten there, but she knew enough to feel fear.

Kaite O’Brien realized she wasn’t having a nightmare, but waking up into one. She feared she had been assaulted.

In a Chicago emergency room that morning in 2009, her attending nurse was kind, she recalled, but clearly nervous as she opened the evidence collection box known as a rape kit.

“It’s a little weird to hear, ‘Oh this is the first time that I’m doing this,'” said O’Brien, 34. “It makes you feel very unimportant. Like what had happened to me wasn’t a big deal, so it doesn’t require someone who really knows what they’re doing?”

O’Brien’s experience in the emergency room isn’t unusual.

There are more than 196,000 registered nurses in Illinois. Only 32 nurses in the state are certified by the International Association of Forensic Nurses to work with adult sexual assault patients. Twelve of these sexual assault nurse examiners, known as SANE or forensic nurses, are certified to treat children.

Nearly 4,500 patients were seen in emergency rooms in the state for alleged, suspected or confirmed sexual abuse or rape in 2016, the most recent year the Illinois Department of Public Health has data available. And not every victim goes to a hospital. Last year, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority data recorded almost 10,000 people who received services from state-funded rape crisis centers.

Despite health and government officials’ recommendations that sexual assault patients be treated by nurses trained to recognize trauma and collect evidence, many nurses receive no such training.

Recently, the attorney general’s office said it is working with Illinois lawmakers to draft legislation that would require hospitals have a specially trained medical provider present within 90 minutes of a sexual assault patient’s arrival. Hospitals would be required to implement this by 2023.

In a statement, the Illinois Health and Hospital Association said the group supports SANE programs but that training so many nurses, in a specialty the group says few pursue or complete, is not feasible within that time frame.

Ann Spillane, the chief of staff for Attorney General Lisa Madigan, said hospitals refuse to prioritize staffing of trained professionals to treat victims.

“In this midst of the #MeToo movement, it couldn’t be more clear that providing compassionate care to sexual assault survivors is not the hospitals’ priority,” she said.

In an effort to increase the number of forensic nurses, three years ago the attorney general’s office hired emergency room nurse Jaclyn Rodriguez to train her peers. She estimates 150 nurses in Illinois emergency rooms have completed the required 40 hours of training in sexual assault care and additional clinical work to practice as a SANE. But for national certification, nurses must pass the International Association of Forensic Nurses exam, and only 32 have completed that requirement.

During a weeklong February training session at West Suburban Medical Center, Rodriguez told about 50 attendees that just a quarter of them would finish the clinical steps, which include practicing genital exams and observing expert witness testimony in a criminal trial. She said the time it takes to complete this process is time that nurses don’t generally have off.

The nurses watched attentively as Rodriguez explained how to record injuries they might see: cuts, bite marks, lacerations.

“We definitely have a lot of interest,” said Rodriguez, whose February training session had more applications than she had slots. She holds two others throughout the year in different parts of the state.

A well-trained nurse recognizes signs of trauma and asks questions in a way that doesn’t add anxiety, said Colleen Zavodny, DuPage County coordinator of advocacy and crisis intervention at YWCA Metropolitan Chicago.

Someone with no training might make a victim feel guilty or doubted by asking questions such as “How much did you drink?” Phrasing questions in this way can imply fault or disbelief, which can compound a victim’s stress.

“We call that the second rape,” Zavodny said.

A trained nurse collecting evidence also can bolster a prosecution against an offender, said Cindy Hora, the division chief of Crime Victims Services at the attorney general’s office.

“We do end up with more charges and more convictions,” she said. These nurses are also trained to testify, which can be especially important in pediatric cases.

When Elmhurst Hospital nurse Kerry O’Connor meets a victim of sexual assault, she begins by introducing herself as a SANE nurse. Then, the two simply talk. They might talk for an hour, if that’s how long it takes for the patient to become comfortable with a procedure that is intrusive. She says they can pause at any point. She explains it’s up to the victim to do a rape kit or not, and to provide it to police or not. She explains evidence, fingernail scrapings, vaginal swabs, collecting clothing.

“I want them to feel like they’re in control,” she said. “I don’t want them to feel like someone forcibly did this to me, and now I’m in a medical setting where someone is doing what they think should be done.”

As Lindsey Ross wept in an Evanston emergency room during a rape exam in 2014, she remembers, a nurse told her it didn’t hurt.

She remembers because it did hurt. It hurt a lot. She cried as the nurse scraped and swabbed her body for evidence in the same area where she’d been violated hours earlier.

“It was so intrusive and so, so cold,” Ross, 24, a speaker with Rape Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), recalled.

She said it felt as if questions just kept coming at her. And almost immediately, she doubted whether anything would happen with her case. “I was scared that they didn’t believe me,” Ross said of the officers and the nurse asking questions.

Noting that sexual assault patients warrant special care, state legislators allotted funding in 1999 to establish four SANE programs in Illinois. A 2003 report recounted better outcomes for victims, who were more likely to file police reports. With SANEs collecting evidence, police made more arrests, and more defendants pleaded guilty. The report encouraged 24-hour access to these trained nurses.

That seemed, said Jennifer Hiselman, who worked on the report for the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, a “no-brainer.”

But 15 years later, the level of care a victim receives depends on which emergency room he or she ends up in, and when. At one hospital in the state a victim might be treated by a nurse with a decade of specialized training. But in another, the victim could encounter a nurse collecting evidence for the first time.

“There is no consistency,” said Sarah Layden, director of programs and public policy at Rape Victim Advocates.

Some nurses are trying to change that.

As a mom of five, O’Connor splits her time between hockey practices and overnight shifts at Elmhurst, which saw 50 sexual assault patients last year. She also volunteers to be on call for rape exams.

Her hospital system employs 10 nurses trained to work with sexual assault patients. To maintain SANE certification, O’Connor completes continuing education. Recently, she learned how bruising in a patient’s mouth can indicate strangulation. Without training, she never would have known to check.

Many nurses said they sought training after feeling they had not given their best to a sexual assault patient.

Early in Melissa Cochrane’s career, she was the only female nurse in a Chicago emergency room when a sexual assault patient came in.

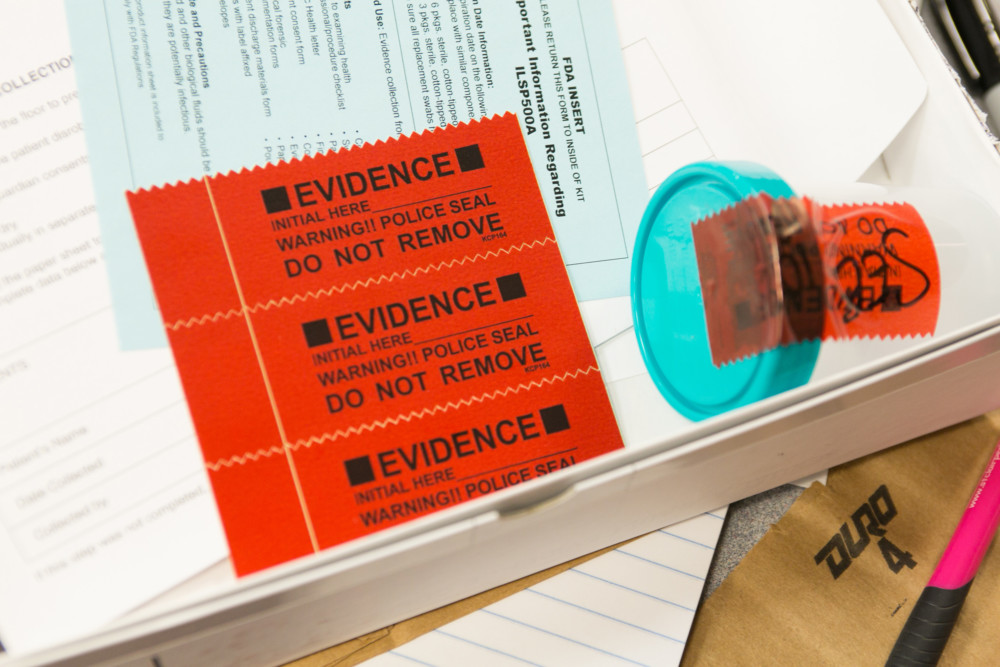

Cochrane had never opened a rape kit. She peeled back the red tape on the white box that showed instructions for 15 steps.

“I remember sitting there and reading the box and not knowing what I was doing and just feeling very overwhelmed,” she said. “And I’ll think about that person for the rest of my career.”

Now, she is working toward SANE certification. At Swedish Covenant Hospital, she and fellow nurses are paid for their time in training.

On a recent morning, sitting in a private room created for sexual assault patients, the staff discussed ways to improve care, including securing a female translator for non-English speaking patients, ordering speculums that are different sizes, and whether to allow patients to scrape their own fingernails to offer a sense of control.

At some Chicago hospitals, nurses spend their own money for exam fees and vacation days for training.

“I think the biggest barrier is just getting hospitals to rethink their traditional staffing,” said Spillane.

“Ultimately, we would like to see a SANE nurse who’s available at every hospital 24/7, but we’re obviously a ways away from that.”

Only a law, says Christine Chaput, a nurse in charge of staffing at Emergency Medical Services at St. Anthony Hospital, will equalize every hospital’s commitment to staffing nurses trained in sexual assault.

“They require so many other things,” she said. “So why would you not require a hospital to have, at minimum, one SANE nurse per shift?”

O’Brien, who woke up scared in a stranger’s apartment nearly a decade ago, sits with victims during their rape exams as part of her volunteer work with Rape Victim Advocates. She said she’ll always wonder what difference a trained nurse might have made.

“It’s one less thing to worry about on a day when everything is horrible,” she said.

___

MORE INFORMATION

The Chicago rape crisis hotline is 888-293-2080. More information is available at Rape Victim Advocates, which provides counseling and other services.