By Jon Talton

The Seattle Times

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) According to reporter Jon Talton, “Bottom line: America doesn’t create nearly enough good or promising jobs for its workforce without bachelor’s degrees. And even many industries that provide that work now are vulnerable to automation. (College grads won’t be safe from this, either.)”

The Seattle Times

Washington’s unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in November, a historic low. Seattle stood at 3.3 percent. Given the unsettling turbulence in the stock and bond markets and potential for a slowdown, this may be the closest to full employment we see in our lifetimes.

Yet not all the jobs are good ones, with at least middle-wage pay and benefits. This is especially true for those with less education and lacking high skills.

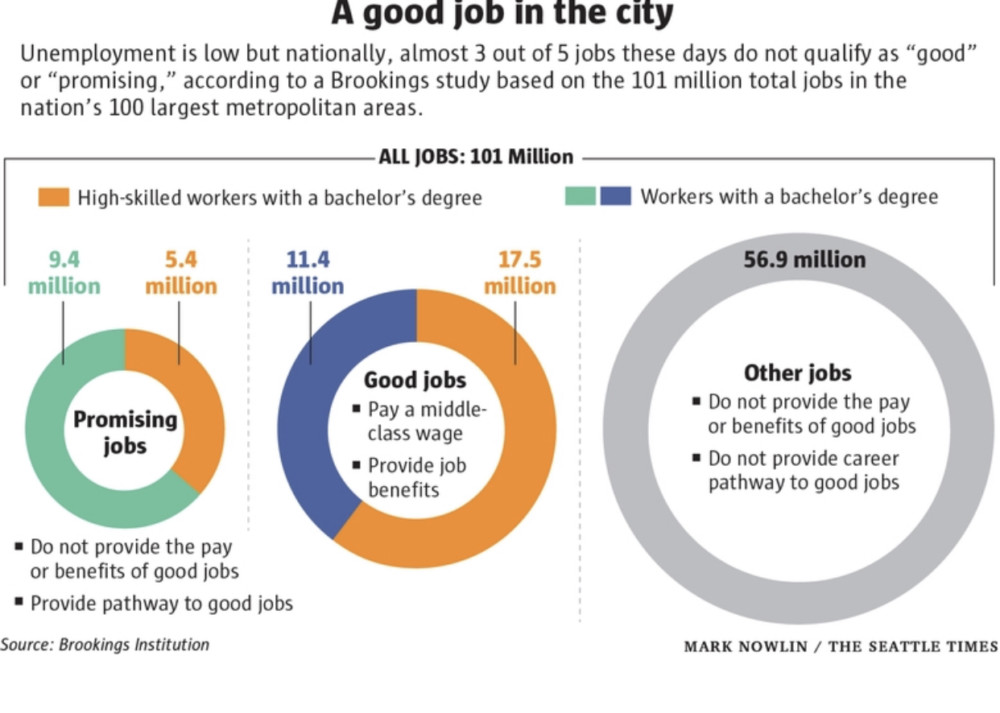

An analysis of employment in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas by the Brookings Institution found that only one third of workers without bachelor’s degrees held good or promising jobs in 2017.

“Good” means middle-class pay and benefits, while “promising” jobs provide pathways to good ones.

The results are nearly flipped for those with a college degree. And the national data pretty much play out the same in Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue.

A good job, offering “the right to rise,” was a cornerstone of the American dream as formulated for decades in the 20th century. It helped create the largest middle class in the history of the world.

This work was fairly accessible to the white majority with or without college. Indeed, in 1940, only 4.6 percent of all adults had a degree.

That circle of opportunity and prosperity widened to include more minorities during and after the civil-rights era.

From the 1940s into the 1970s, all income groups rose in similar fashion, too. Income inequality was much lower than today.

Millions of Americans worked in railroading, auto plants, steel mills, shipyards (and, yes, coal mines, nearly 400,000 in 1950). In most of these mammoth enterprises, workers could begin at the bottom of the ladder, gaining skills and pay as they stayed, helped by unions. A bank teller could rise to vice president without a college degree.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters became the genesis of the black middle class, and a potent political force under its leader, A. Philip Randolph.

No single change marked the inflection point that led us to today.

Germany, Japan and South Korea became export powerhouses as their economies were rebuilt from the ruin of World War II. In many cases, their products were superior to American-made goods.

The great merger mania of the 1980s mowed down companies and whole industries, especially hurting employment in the Rust Belt. Top executives failed to invest in modernizing their domestic plants, making their sectors less competitive against imports.

“Shareholder value” became a ruling force for public companies, redistributing wealth upward to shareholders and top executives at the expense of wages, job creation and investment in the future.

Union busting was endorsed by President Ronald Reagan, the only former union president to occupy the Oval Office.

Coal jobs were steadily done in by low-employment open-pit mines, long before the effects of environmental regulation kicked in. Now natural gas is coal’s enemy.

Technology became the enemy of low-skilled and less-educated workers, too. For example, diesels replaced steam locomotives, eliminating millions of railroad jobs. A freight train once required a crew of at least five; now it’s two, and rail companies are experimenting with wholly automated trains. America’s world-leading passenger trains were replaced by the skeleton system of Amtrak.

Deregulation eliminated jobs by enabling industry consolidation and taking away secure employment in such sectors as telecommunications.

And globalization sent jobs overseas, including fields where America once ruled, such as manufacturing everything from televisions to machine tools.

The result is a workforce where the better educated and highly skilled do well, while the rest lack the rungs up the ladder that once existed. By 2016, held bachelor’s degrees.

Now, someone doesn’t necessarily need a college degree to rise. But lacking that, they need specific skills, especially in the largest sectors of production and construction. (Fun fact: In Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, the sector that contains the highest concentration of good or promising jobs without a degree is mining. The bad news is that this consisted of only 810 positions in 2017).

Bottom line: America doesn’t create nearly enough good or promising jobs for its workforce without bachelor’s degrees. And even many industries that provide that work now are vulnerable to automation. (College grads won’t be safe from this, either.)

Brookings scholar Chad Shearer and research assistant Isha Shah argue that willingness to move and change jobs is essential for less-educated workers.

“Occupations that provide the best chances of obtaining a good job typically require specialized skills,” they write. “Yet few people follow a specific career pathway to get one. Instead, most people who obtain a good job do so by switching from an unrelated occupation …”

More than 71 percent of these less-educated workers who win a good job by 2027 must make a major career switch. The “most promising career pathways to good jobs are ‘lattices’ that run across occupations rather than ‘ladders’ that exist within them,” they write.

Shearer and Shah recommend policies that incentivize industries that create large numbers of jobs, public-private partnerships to improve job quality and education and workforce development that can train people for today’s dynamic economy.

I would add reversing the emphasis on shareholder value through progressive taxation, investing in advanced job-creating infrastructure and making unionization easier. And, don’t engage in trade wars.

Otherwise, too many workers will continue to get skimpy paychecks and downward mobility. That’s the lump of coal in the holiday stocking of the American dream.