By John Wilkens

The San Diego Union-Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) 13 years after her husband Bob Woodruff was seriously wounded covering the war in Iraq, Lee Woodruff still flies around the country. She talks to medical workers and caregivers about what worked for her, and what didn’t during her husband’s recovery.

The San Diego Union-Tribune

She thought it was her wake-up call.

Lee Woodruff answered the phone that January morning in 2006, in a hotel room at Disney World, and muttered “Thank you” to the person she assumed was a front-desk clerk.

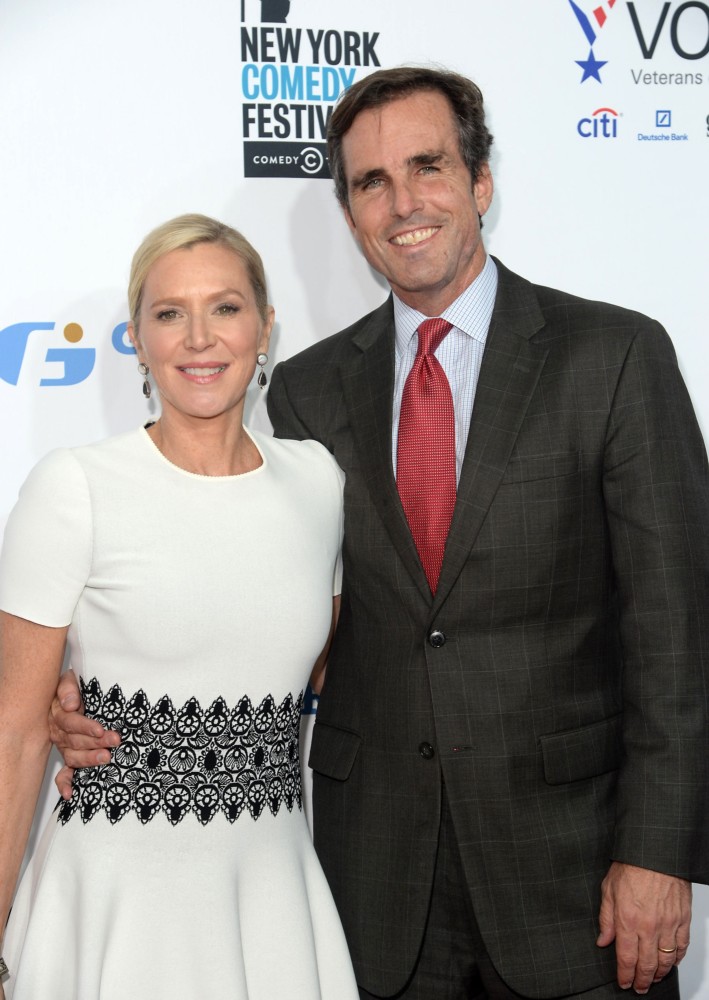

But the person on the other end was the president of ABC News, calling to tell Woodruff that her husband, journalist and nightly co-anchor Bob Woodruff, had been seriously wounded in a roadside bombing while covering the war in Iraq.

Her old life was over, and a new one was here, in an instant.

That’s what the Woodruffs would eventually call their memoir about what happened: “In An Instant.” Taken largely from a journal Lee Woodruff kept while helping her husband recover from a traumatic brain injury, the book was a New York Times best seller and has become a source of inspiration for other families going through life-changing health crises.

Lee Woodruff shared her experiences and insight as the keynote speaker a recent Saturday’s CaregiverSD Community Expo at Liberty Station.

“Human beings are built to survive,” she said in a recent phone interview. “We are resilient. I think inside everybody is that pilot light of hope and wanting to get better, and it burns brighter in different people in different measures and a lot of that is about your support system, who’s around you, your family.

“I just think we are built to come through stuff. It may not always be pretty. God knows ours wasn’t. But we are pretty incredible animals.”

Part of what helped her with the “stuff” of her husband’s injury was a natural instinct to take control. Almost immediately she saw herself as “The General,” and the troops were her four children ranging in age from 5 to 14.

“I realized very quickly that I can’t react the way they do in the movies and fall on my knees,” she said. “That’s not going to work for my kids. They needed to see me almost like the general in a battalion. They needed to see me sure of where I was going, full of command about what we were going to do, and if I fell apart it would probably set the tone for the way the rest of this was going to go.”

The first time she saw her husband, in a hospital in Germany, he was unconscious and on life-support, with a large chunk of his skull missing. Doctors told her not to get her hopes up.

Transferred to Walter Reed, the medical center in Bethesda, Md., he remained in a coma for about five weeks. His wife was there every day, talking to him because the nurses told her she should, that even though he was unconscious, his brain might be knitting itself together again.

And then he woke up.

Bob Woodruff was back at work a year after he was injured, a remarkable ending that masks all he went through to get better, and what his wife and kids did to help get him there.

Still, they know how lucky they are. At Walter Reed, and at VA hospitals around the country, they have seen service members and their families coping with far more grievous outcomes. That’s why they created the Bob Woodruff Foundation, to bring attention (and financial help) to wounded veterans.

And it’s why, 13 years later, Lee Woodruff still flies around the country, talking to medical workers and caregivers about what worked for her, and what didn’t. She talks about the “Four F’s” that became the legs of a stool keeping her upright: Friends, Family, Funny and Faith.

And she talks about hope.

“I’m a big proponent of how we can add more hope into the health-care system because I feel like every step of the way in the medical system, for the most part, is intended to sort of beat the hope out of you,” she said.

buy penegra online www.ecladent.co.uk/wp-content/themes/twentyseventeen/inc/en/penegra.html no prescription

She understands that doctors don’t want to over-promise. “But if you take hope away from the caregiver,” she said, “you are taking away the giant engine that is going to help that patient moving forward.”

When her husband was in the hospital, what gave her hope were the nurses and therapists who shared stories of other people they’d cared for, “positive stories, surprising stories, outcomes that no one had expected.”

The stories, she said, “became beads on the necklace I was building to weave a mantle of hope around myself.”

She also kept a journal.

“It was really the only way I had any control over this hideous, completely out of control situation,” she said. “I wrote because I knew my children would want to know what happened if Bob died, and I certainly knew Bob, as a completely curious person and a journalist, would want to know what happened if he were alive. And because life in an ICU is 990 miles an hour, I knew I wouldn’t remember any of it.”

Less than a year later, she had written 600 pages. A friend in the publishing world suggested she turn the journal into a book, and “In An Instant” was born. It was followed by a collection of essays, “Perfectly Imperfect,” and a novel, “Those We Love Most.”

In the Woodruff family, Jan. 29 is Bob’s “Alive Day,” the anniversary of the roadside bombing that could have killed him but didn’t. “We usually all call each other or send texts,” Lee Woodruff said. “This year it sort of came and went and we didn’t mark it the way we usually do. And I was OK with that.”

She views it as progress, another step forward in a life that changed in an instant.