By Michael Ollove

Stateline.org

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) As Michael Ollove reports, the crisis has pushed many primary care practitioners, especially those in small, unaffiliated practices to the brink, threatening them with insolvency.

Washington

If Dr. Erica Swegler, a solo primary care doctor in Austin, Texas, hadn’t gotten her bank to delay payments on one of the loans she had taken out to open her practice five years ago, she said, “I would have been out of business in April.”

Likewise, she’s sure she would have had to close if she hadn’t also received a $36,000 federal Payment Protection Program coronavirus loan to carry her over a couple of months while her patients stayed away in droves. Ditto if Medicare and Medicaid hadn’t relaxed rules to allow for compensation and better reimbursement rates for telehealth visits with patients, including telephone consultations.

Even with all that assistance, she said, “We’re running a $10,000-a-month deficit, which isn’t sustainable over any length of time.”

In other words, she’s still in trouble, even if patient medical visits have drifted back up to 80% of normal from a low of 30%. “I thought I was seeing a light at the end of a tunnel,” she said, “but it wasn’t. It was a train coming at me.”

The pandemic has wreaked havoc on all levels of medicine, not least of which are primary care doctors, arguably the front line in trying to keep Americans healthy and out of hospitals. While many practices, primary care and otherwise, have seen business pick up significantly since the lows of March and April, few have come close to full recovery, which is perilous for practices that operate with low margins in the best of times.

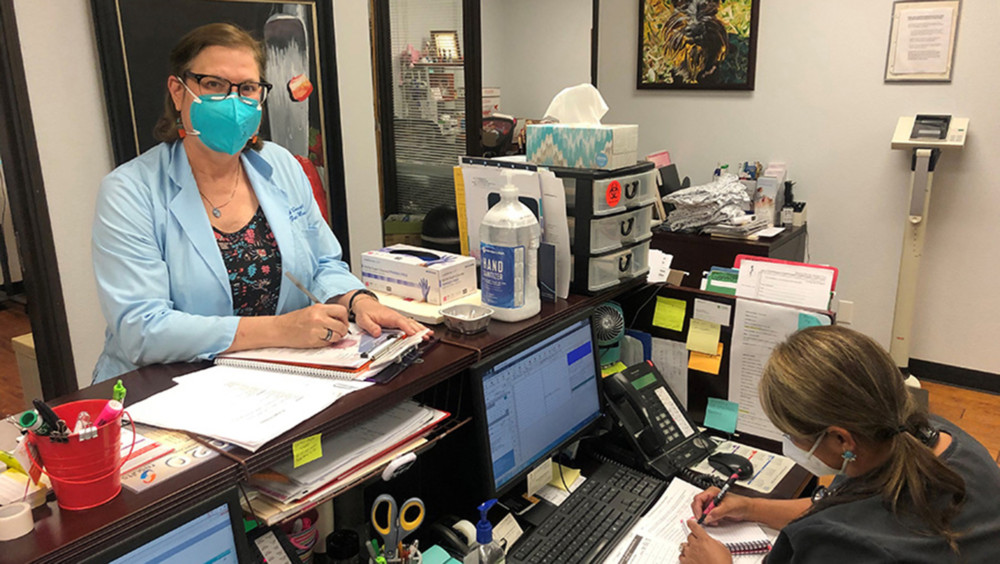

The crisis has pushed many primary care practitioners, especially those in small, unaffiliated practices like Swegler’s, to the brink, threatening them with insolvency.

Many admit to fears of being forced to abandon their independence, which they believe best serves their patients and communities, in favor of the stability coming from joining larger medical groups or health systems or selling their practices to equity interests.

“As it goes along, there will be more pressure on unaligned primary care practices to partner up with insurance, hospitals or like-minded colleagues,” said Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians. “It’s really going to be difficult for those practices to survive long term.”

The Primary Care Collaborative, a nonprofit that advocates for primary care, and two partner organizations published the results of a survey conducted in late June: Forty% of primary care providers said they weren’t sure they could stay open through August. More than a third said they were not prepared for COVID-19 surges or the fall flu season.

Dr. Christopher Crow, president of the Texas-based Catalyst Health Network, an organization of a thousand independent primary care doctors, said the network has received at least 600 calls from physicians since the pandemic began inquiring about joining. The network says it is able to provide savings and support services to member doctors through an economy of scale and negotiating power with insurers and pharmacies that small practices on their own can’t achieve.

“They say to me, ‘Oh my God, that’s what I need. I don’t see how I’ll survive unless I’m connected to those kinds of services,'” Crow said.

Primary care is certainly not the only specialty suffering. Dr. David Smail, a surgeon in Beverly, Massachusetts, said the state’s prohibition against elective surgery had reduced his patient volume between 75% and 80% from mid-March to mid-May with a commensurate loss of revenue. Those weren’t patients waiting for cosmetic nose jobs, he said. “I was sitting on patients with breast cancer waiting. People who had gallbladder attacks after every meal, people with hernias.”

Dr. David Hoyt, executive director of the American College of Surgeons, said surgeons had seen volumes of surgery drop by 70-80%. In a survey published by the group in June, one third of surgeons questioned said they were considering either shutting their practices or limiting business to patients whose insurance plans fully reimbursed for all surgical care.

“The consequences will be truly profound if we are not careful,” Hoyt said. One of those consequences, he said, is further consolidation in medicine, which health policy experts generally agree would reduce patient access and drive up costs.

The merging of independent practices, particularly in primary care, into larger health or hospital systems didn’t start with the pandemic, Banning said. The finances of primary care have always been tough, especially under a fee-for-service reimbursement system in which doctors are paid based on specific services and procedures rather than time spent with patients to comprehensively understand and address their health care needs.

“A major worry is the pandemic will accelerate or some would say complete a level of consolidation” that has been occurring for years, said Dr. Eric Schneider, a physician and senior vice president for policy and research with the Commonwealth Fund, a foundation that funds health policy research.

Independent doctors sound as if they have come through a whirlwind but are still far from steady on their feet.

“Every day is a new challenge because the situation seems to constantly change,” said Dr. Mary Nguyen, who, with her physician husband, operates a practice in rural Texas about 30 miles west of San Antonio. “I never know what I’ll find. Is it five patients today or 15? The schedule is different every day.”

The stress, she said, is through the roof. “I worry about the mental health of my staff as well as myself and my husband.”

Patient visits, even with expanded use of telemedicine, fell by about 50% after the onset of the pandemic, she said. “Revenues have been down month to month between 30 and 50%,” she said. The number of visits started to climb in May and June, but with the recent surge of cases in Texas, she said, “our visits are going down again, slowly.”

“A lot of patients didn’t want to come to the office because they were scared,” Nguyen said. “A lot thought we were closed when we weren’t. A lot prefer to wait. Some are willing to do telemedicine. Others not.”

She is staying afloat thanks in part to the rent she charges a couple of tenants in her clinic’s building.

She received a Payment Protection Program loan of $117,000, which enabled her to continue to pay the staff, but that money is running out, with no sign from Washington that the program will be renewed. She has had trouble finding even basic sanitary supplies. “Right now, we’re having problems finding disinfectant wipes,” she said. “We are getting baby wipes and dipping them in alcohol.”

Nguyen worries about her many patients who have chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure but cannot monitor their conditions without coming to the office for lab work or examinations.

Many of them, she said, are out of work because of the pandemic and rationing their medicines instead of taking them every day as prescribed.

“The temperature outside here is 105 degrees,” she said. “They are thinking, ‘Do I pay for utilities or do I pay for medication?’ Health gets pushed back because the effects don’t seem as immediate to them.”

Elsewhere in Texas, Dr. Lane Aiena, who is in a six-doctor practice in Huntsville, said that after a steep drop in appointments, he is busier now than before the pandemic thanks to pent-up demand. But the early days were grim, no more so than after one of the clinic’s nurses tested positive and he slept in his office for three nights while waiting for his own negative test result to arrive. He didn’t want to chance bringing the infection home to his 1- and 3-year-old children or to his wife.

“That was hell, absolute hell,” he said.

As with many practices, he and his fellow doctors relied heavily on telemedicine, benefiting from loosened federal reimbursement policies, and adopted strict protocols for treating patients in the office, including temperature checks and social distancing. Also like many others, he often dons a mask, gown and gloves to venture into the parking lot to meet symptomatic patients in their cars.

He still marvels over what changes have occurred since the beginning of the year. “In January I wasn’t concerned about COVID at all,” Aiena said. “I was more concerned about whether LSU (Louisiana State University) would win the national championship.”

Dr. Jacqueline Fincher, an internist in a rural area of eastern Georgia and the president of the American College of Physicians, said that when alarms sounded loudly about the virus in early March, “We had cancellations right and left.”

Although her five-physician practice, part of a bigger 36-doctor network in and around Augusta, was able to quickly get up and running on telemedicine, something unheard of in the network previously, it wasn’t useful for many of her patients. Some don’t have computers and others have connectivity problems, a familiar problem in rural America.

“It was frustrating,” Fincher said, “when you have only 15 or 20 minutes with a patient, and you’re spending more than half of that time trying to get connected.”

And, she said, despite all the promise of telemedicine, it has its limitations. “The bottom line is that as primary care doctors we’re trained to lay hands on the patient to do diagnoses.”

Thanks to the muscle of Fincher’s network and her organization, the American College of Physicians, she has been able to secure sufficient personal protective equipment.

That has not been the case for Swegler as a local practitioner with few support services. She hasn’t been able to find enough of those supplies, at least for purchase. Instead she has had to rely on patient donations. The practice was given protective gowns sewn by the mother of one of her nurses.

Fincher said that patient visits declined by 35% in the first month. The resulting revenue loss was compounded because her clinic, like many others, also makes money from so-called ancillary services, such as laboratory work, monitoring tests, like EKGs, and vaccinations. With patients avoiding office visits, most of that revenue dried up.

The $3.2 million Payment Protection Program loan her network received has helped, but, as Fincher said, it must be paid back. The coronavirus loans can be forgiven if employers retain their workers, which has not been possible for all practices. In her capacity as president of the 163,000-member American College of Physicians, she sent U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar a letter asking for outright federal allocations to primary care providers.

“I keep watching on my phone looking for an announcement that it’s being extended for another 90 days,” Fincher said.

Few primary care doctors have excess energy to contemplate what the future of their area of medicine will look like after the pandemic. But Aiena, the LSU Tigers fan, said he is pretty sure that there will never be a return to complacency.

“There’s always going to be this specter above us,” he said. “We’re going to be going, ‘What did I hear them say on the news? Is it happening again?'”

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.