By Heidi Stevens

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Heidi Stevens shares why Aly Raisman’s new book is such a powerful reminder of how WE as women determine our future, not anyone else.

Chicago Tribune

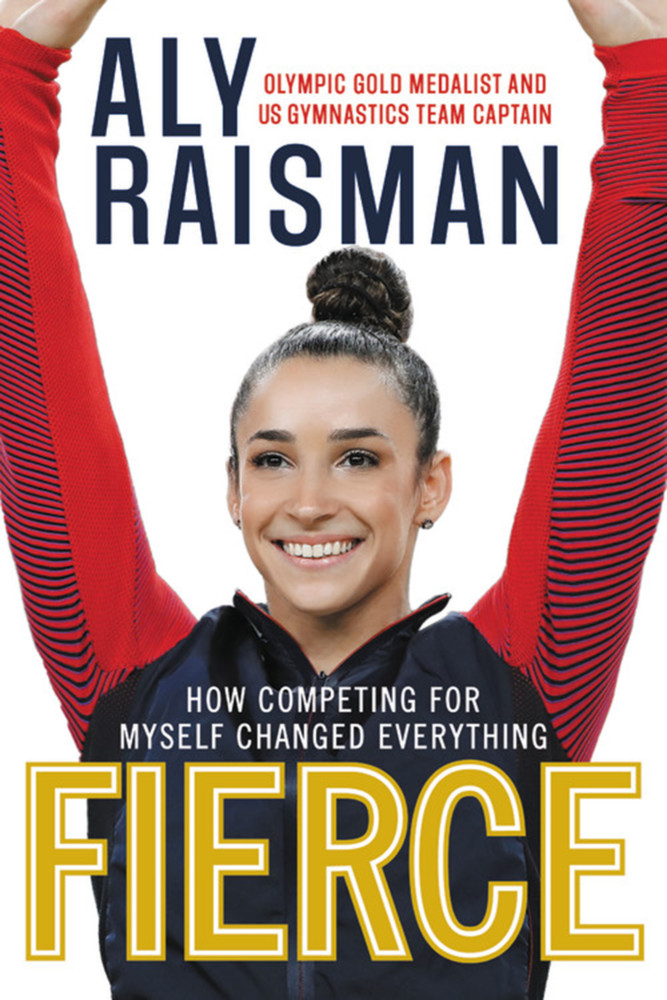

I’m just now catching up with Aly Raisman’s book, “Fierce: How Competing for Myself Changed Everything,” and there’s a passage I want to tell you about.

Raisman is a two-time Olympian with six medals, three of them gold, who served as captain of the U.S. gymnastics teams in both London (2012) and Rio (2016).

Her book is about her family (she’s one of four kids), her lifelong dream of becoming an Olympic gymnast and her path to getting there.

Raisman is also one of more than 100 athletes who spoke out about sexual abuse they suffered at the hands of Larry Nassar, a sports doctor for the U.S. Women’s National Team and Michigan State University.

buy orlistat generic buy orlistat online no prescription

Raisman’s victim impact statement, which was met with applause in the courtroom, is widely credited with crystallizing the weight of Nassar’s crimes for the viewing public. The New York Times devoted a full page to reprinting it.

“Larry, you do realize now that we, this group of women you so heartlessly abused over such a long period of time, are now a force and you are nothing,” Raisman said in her statement. “The tables have turned, Larry. We are here, we have our voices, and we are not going anywhere.”

Nassar occupies very little space in “Fierce.”

“I am not going into specifics about what Larry did to me, that information is private,” Raisman writes.

She shares some basics, the call she received from USA Gymnastics telling her a private investigator would be visiting her, her years-long internal conflict over whether Nassar’s methods were as violating as they felt, her hope that her story will inspire other abuse survivors to speak up.

Most of her story, though, is not lived or told under his shadow. As it should be.

The passage in “Fierce” I was most struck by is about her decision to pose for ESPN magazine’s Body Issue, which is filled with artfully shot, naked images of athletes.

Her first instinct was to say no when the magazine came calling.

“I pictured myself typing my name into Google, knowing that naked photos of me had been published, and there was nothing I could do if I didn’t like what I saw,” she writes. “I also wondered how the people I knew would react. My coaches, for example.”

She talked it over with her parents and siblings. “Why would you want to?” one sister asked.

“If I were a man, this would be no big deal, I told myself,” Raisman writes. “Men pose for these things all the time. Why is it different because I’m a woman?”

She thought about all the ways girls and women are judged for the ways their bodies look, too small, too big, too muscular. “They are taught to dislike what makes them stand out,” she writes.

“I had worked my whole life to look the way I did, and I was through letting anyone make me ashamed of my body,” she writes. “I was now 20 years old, and training for a second Olympics had made me appreciate my body like never before.”

Why shouldn’t she be included in a Body Issue?

“I had always weighed decisions by asking myself, ‘What will everyone else think?’ first and ‘What do I want to do?’ second,” she writes. “It was time to listen to my voice above the others.”

She called the magazine to accept.

“When I spoke, my voice was firm,” she said. “‘I’ll do it.'”

How many of us have spent decades (a lifetime?) weighing decisions, first, by asking what everyone else will think?

How many of us have only recently learned, are still trying to learn, to listen to our own voices above others?

How many of us are raising children to listen to and use their own voices?

Raisman’s book, as I said, is about her. Not Nassar.

But I can’t help but place her epiphany next to what she writes about his abuse.

“There seemed to be so many reasons not to speak up,” she writes. “First of all, what if I was wrong? Maybe what he did was a legitimate medical practice, just like he said all along. Maybe people wouldn’t believe me, or would think I was exaggerating and being dramatic, or they’d hate me. Maybe they would think that I was doing it just to get attention. And then there was Larry’s family to think of. What if I ruined their lives?”

In the end, she found the courage to listen to her own voice above the others.

Nassar was sentenced in January to 40 to 175 years in prison for multiple sex crimes. That wouldn’t have happened without her voice and the voices of more than 100 other survivors who came forward.

“To everyone reading this,” Raisman writes. “Your story matters. You matter, and you should trust yourself. If something feels off, and you think you may be being manipulated or taken advantage of, speak up. You are strong and tough. You are not alone. You deserve to feel safe. It’s as simple as that.”

And it starts with listening to your own voice above others.