By Heidi Stevens

Chicago Tribune.

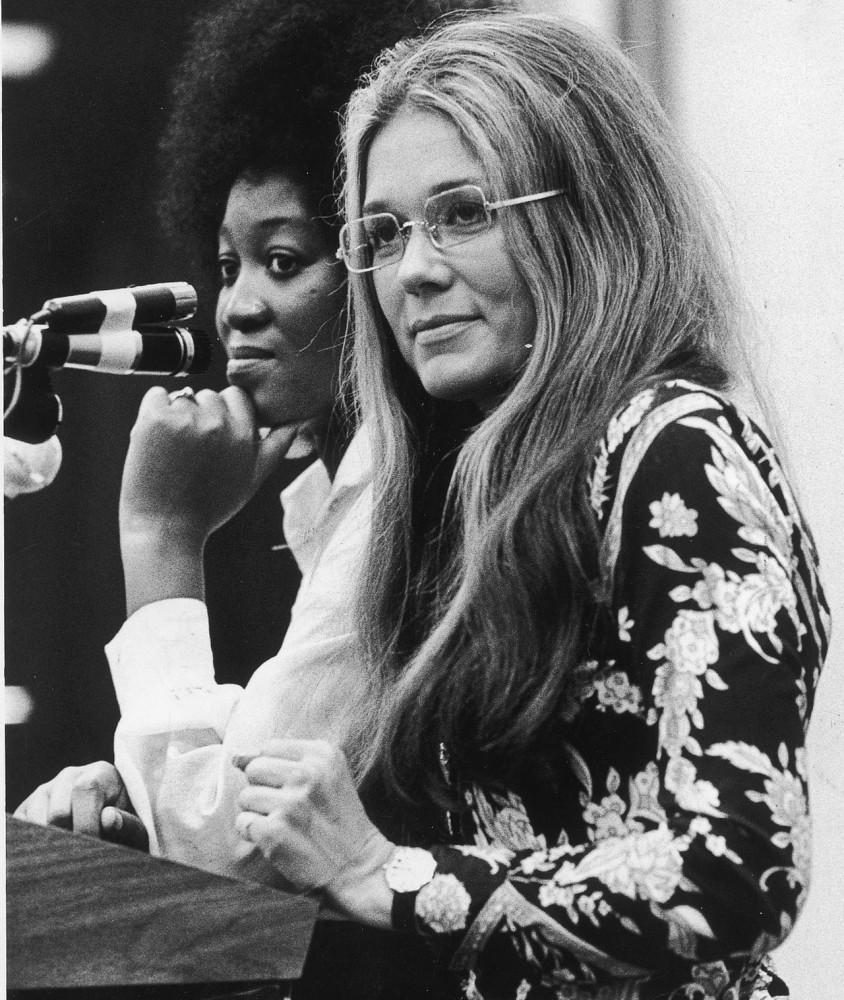

Gloria Steinem’s new book, “My Life on the Road” (Random House, to be released Tuesday), begins as a love letter to her father, her first traveling companion, and winds beautifully through her eight decades of life, stopping along the way to capture moments that forever changed our world.

The road is where Steinem, 81, spent most of her childhood, where she learned to read (by sounding out road signs; she didn’t attend elementary school) and where she learned to listen, a skill that would shape, more than any other, her place in history.

“I discovered the magic of people telling their own stories,” she writes. “One of the simplest paths to deep change is for the less powerful to speak as much as they listen, and for the more powerful to listen as much as they speak.”

It’s her first book in more than 20 years, mostly, she says, because it took that long to write it.

“I made the proposal and signed the contract two decades ago,” she told me by phone. “I was working on it each summer and then not for the rest of the year, and I’ve been feeling guilty about not finishing it.”

(Am I the only one who takes comfort in knowing that a powerhouse like Steinem procrastinates?)

Nobody’s complaining about the wait.

“‘My Life on the Road’ is filled with beautifully told stories of the people she has spoken with and listened to, been changed by, helped organize, got radicalized by, could get lost in, could get found in,” author Anne Lamott writes. “I began it again the day after I finished.”

So did I.

As a young freelance journalist, Steinem attended Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 March on Washington. She stood next to an African-American woman named Mrs. Greene, a clerk in segregated Washington during the Truman administration.

Greene pointed out to Steinem the dearth of women on the speakers platform, save for Dorothy Height, head of the National Council of Negro Women, who wasn’t even asked to speak.

“Where is Ella Baker?” Greene wanted to know. “She trained all those (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) young people.

What about Fannie Lou Hamer? She got beaten up in jail and sterilized in a Mississippi hospital when she went in for something else entirely. That’s what happens, we’re supposed to give birth to field hands when they need them, and not when they don’t.”

Steinem was riveted.

“I hadn’t even noticed the absence of women speakers,” she writes. “Also, I’d never thought about the racial reason for controlling women’s bodies. I felt some gear click into place in my mind.”

The two women got separated in the sea of humanity before the speech began, but Steinem was forever changed.

And then this:

“As King ended his speech, I heard Mahalia Jackson call out, ‘Tell them about the dream, Martin!’ And he did begin the ‘I have a dream’ litany from memory, with the crowd calling out to him after each image,” Steinem writes. “What would be most remembered had been least planned.

“I hoped Mrs. Greene heard a woman speak,” she writes. “And make all the difference.”

I asked Steinem whether she kept journals during her travels. She didn’t.

“Your memory is a pretty good editor as to what was important to you,” she says.

And a memoir is a good indicator of what remains so.

Steinem writes lovingly about both of her parents, neither of whom gave her stability, but each of whom shaped her profoundly.

Her dad rarely had steady work and moved his family from town to town for most of her childhood. Her mother, prone to anxiety attacks, didn’t join young Gloria and her dad for many of their adventures.

A life on the road allowed Steinem to watch the world changing in real time. Writing about it deepened her appreciation for those changes.

“The culture had told me, and I believed well past 50, that if you were on the road, you didn’t have a home, and if you had a home, especially for women, you didn’t go on the road,” she told me. “Over the course of writing the book, I discovered that we all need both.

“And I realized again how much my parents had missed,” she continued. “Because my father was always on the road with no home, and my mother was the opposite _ she never had her own journey.”

Steinem’s life and work, though, made it possible for countless women to forge their own.

ON PLAYBOY, CHICAGO, PARENTING AND MORE

In 1963, Gloria Steinem went undercover as a Playboy bunny, working in the Playboy Club in New York under the pseudonym Marie Catherine Ochs and writing about the (rather awful) experience in Show magazine.

She took issue with Playboy’s male-centric approach to the sexual revolution, as well as the paltry pay and hostile working conditions the bunnies were subjected to.

I interviewed Steinem the same week Playboy announced it would no longer feature photos of nude women in its upcoming issues, and I asked Steinem for her take on the news.

She wasn’t impressed.

“For Playboy to stop publishing nude photos of women is like the NRA saying it’s no longer pushing handguns because machine guns and assault weapons are so easily available,” she told me. “Playboy would have to change its title, heart and brain cells in order to express the full humanity of men or women.”

Other highlights from our conversation:

On egalitarian parenting: “More men are raising their own children in a way that was not true in other generations, but the system hasn’t changed. Suppose a man wants to take paternal leave; he still may be penalized by his colleagues. … It’s as crucial for men to be part of home life and be raised to raise children as it is for women to be raised to work. The qualities that are wrongly called feminine, patience, flexibility, attention to detail, are just as crucial to men becoming whole human beings.”

On those she admires: “I’m inspired by Black Lives Matter. I wish more people understood it was started by three young black women (Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi and Alicia Garza). I haven’t been speaking that often lately, because I’m about to go off on this book tour, but when I do speak, I’ve been ending with their organizing principles: Lead with love; low ego, high impact; move at the speed of trust.”

On Chicago: “What goes on in Chicago is so important to the rest of the country, whether it’s a negative of gun violence or a positive of new ideas about organizing and the president of the United States arriving from there. People look to Chicago, in some ways, more so than New York or Los Angeles. Chicago is the center of the country.”