Alison Bowen

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Alison Bowen shares the story of the history-making all-Black-all female team of OB-GYN medical residents at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago.

Chicago

When Dr. Constants Adams walks into a patient’s room, she can sometimes sense the relief. She’s watched as eyes above masks show surprise, even pride, when patients of color are amazed and comforted seeing a provider who looks like them.

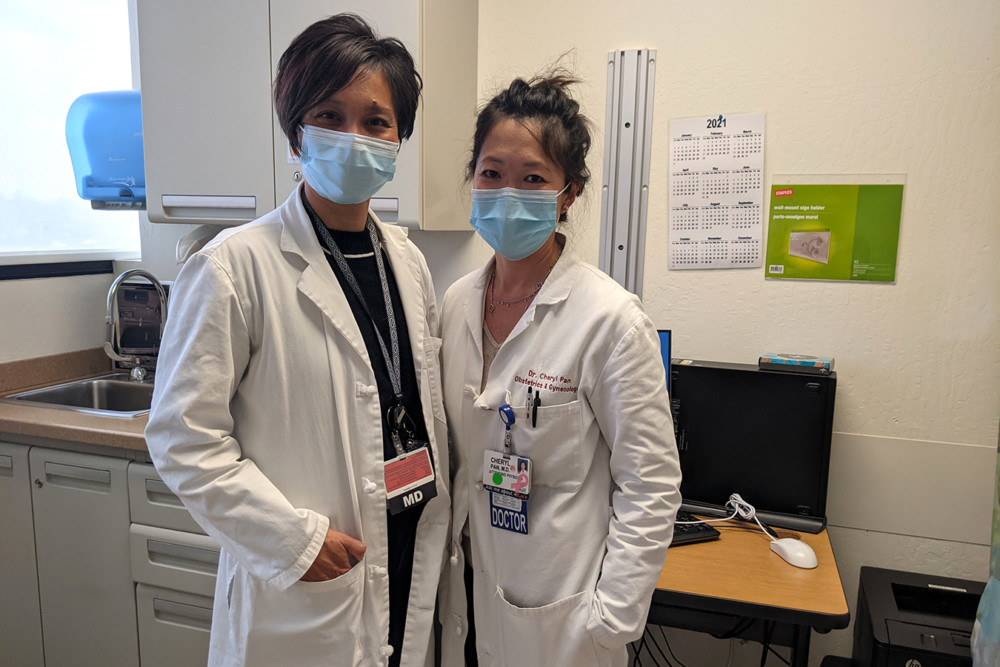

At Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, for the first time anyone at the facility can remember, a team of OB-GYN medical residents is all Black and all female. The five doctors work together daily, treating patients and learning in virtual programs as they work toward becoming OB-GYNs.

It’s an important moment in a field where Black women are six times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes and medicine has been undergoing a reckoning — working to earn trust in communities of color. In Illinois, state legislators are targeting maternal health disparities after calling it a “very dire situation”; also the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed disparities, including among pregnant women. A recent study from the Illinois Department of Public Health revealed that Black women have some of the highest cases of maternal deaths nationwide, as well as in Illinois.

Having providers of color can build trust and help patients feel someone understands some of their life experiences, and is listening. Patients who trust their provider may be more comfortable following their treatment plans and medications.

“I never in life would have thought we’d have an entire Black labor and delivery team here,” Adams said. “It’s a combination of feeling really proud but also feeling a huge amount of responsibility.”

On a recent Friday morning, the group sat in a conference room at Prentice, listening to virtual classes discussing various case studies.

Also in the room was Dr. Tacoma McKnight, the second Black OB-GYN female resident at Northwestern and the first Black female faculty attending physician. Her residency experience looked very different from the Friday morning room of laughing, learning Black women. The only Black woman in her program, she recalled asking others who had gone before her about what the situation would be like.

“One of the things that was discussed was the fact that you would be alone and that while there may not be anyone standing in your pathway of progress, there was not going to be anyone behind you, underneath you, to push you along, carry you along and create that progress that you so desired,” she said.

Working on a shift with this group is a joy, she said. The first time she was with them, she said, “We just couldn’t stop smiling.”

She celebrates the all-Black resident group and said that, although the rotation wasn’t planned this way, it is a result of hospital pushes toward progress. “It’s exciting. It’s validating. It’s just such an exciting reflection of what the world can be.”

But decades after her own residency, McKnight added, “the goal is to make sure that it doesn’t take another 30 years to see another level of progress.”

For Adams, wanting to provide a level of comfort and care to patients of color comes from her own life experiences. As a child, growing up with a single mom, she could sense how her multiple bouts of pneumonia created financial strain and logistical challenges. Her mother ran a home for women being treated for HIV, and she saw that doctors could comfort even as a patient was dying. Later, while helping to coordinate care for homeless women, Adams noticed the absence of even basic medical equipment such as a speculum.

So for her, walking into a room in her white coat is a manifestation of a goal she’s had all her life.

“I wanted to be able to help people like me,” Adams said.

She and the other residents spoke about how patients seem to feel more safe, and seen.

Adams recalled a recent patient’s mother, who was surprised to see not only her, a Black doctor, walk in, but also her colleague Dr. Eseohi Ehimiaghe, followed by Dr. Luce Kassi. Their other colleagues in the cohort are Dr. Mary Tate and Dr. Tamara Weddington.

“I walked back into this patient’s room, and her mom was tearful,” Adams said. “Her mom was just like, ‘I’ve never seen a Black doctor.’ And now there’s five of us.”

Discussing what is different about their interactions with patients, the residents shared multiple examples of patients who had not been treated as the first experts of their own bodies.

“So much of it boils down to listening,” Tate said, as her colleagues nodded.

Recently, a pregnant patient arrived at Prentice feeling symptoms she said reminded her of a previous birth, when she had preeclampsia. Her primary care doctor wanted to send her home, Adams recalled.

Kassi went into the room. After a half-hour, she walked out and told Adams, “I really think there’s something here. No one is listening to this patient.”

They advocated for the patient to stay longer; she ended up having high blood pressure and was induced to deliver. The woman did have preeclampsia.

“We are able to actually listen and stop somebody and really advocate for this patient,” Adams said. “I think, for a lot of people, they hear about OB-GYNs, and it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, you deliver babies — it’s so happy,’ when actually, it’s one of the most stressful times in a woman’s life.”

Residents treat patients at both Northwestern and John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital. Adams sees firsthand the different experiences that can come from access to care or insurance.

For example, at Northwestern, most patients get regular Pap smears, an anchor of preventive care that can flag cancerous cells. Her patients at Stroger sometimes have never had a Pap smear or even known about them. “People have cervical cancer you should only see in textbooks,” she said.

Adams has researched and presented about how the medical community earned distrust of Black patients, including experiments performed on slaves. “It’s really difficult for people to find doctors that are Black or are Latinx, and so when patients find that, they kind of feel safe, and they feel more comforted.”

The residents bonded over how each scoured Northwestern’s site before applying, looking at staff bios and portraits to gauge how many potential colleagues might look like them, understand their life experiences and offer unique support.

“I feel like a lot of us were looking for a place where we could find our people,” Kassi said.

For Adams, having a cohort of Black women has been a support, in many moments, including walking into work after the death of George Floyd, a man who reminded her of her uncle.

At the end of May, their rotation will end. But for now, they keep walking into rooms, ready to help.

“There’s nothing in the world that can describe what that feeling is like for us and for the patients,” Tate said.

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.