Jim Brunner

The Seattle Times

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) As Jim Brunner reports, “Jayapal, vice chair of the House’s antitrust subcommittee, said the big tech companies cannot be trusted to police themselves, and that even beefed-up federal regulation may be insufficient, making forced breakups a necessity.”

Seattle

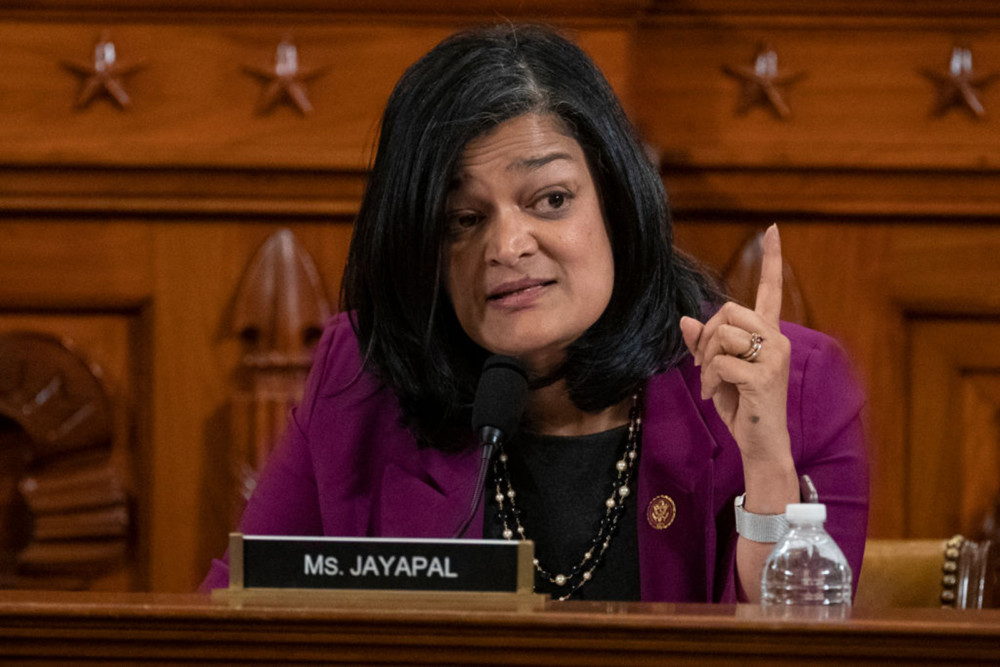

As a general rule, politicians don’t pick fights with their state’s biggest private employers, but Seattle Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal is doing just that, sponsoring legislation that would break up Amazon.

Jayapal’s Ending Platform Monopolies Act is part of a broader, bipartisan effort in Congress to rein in the power of the Big Four tech giants: Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Google.

Following up on a 16-month antitrust investigation completed last fall, House lawmakers this month unveiled five antitrust bills aimed at checking the power of the companies by limiting their abilities to gobble up or hamstring competitors.

Jayapal’s proposal would allow the federal government to sue to force the Big Four tech firms to sell off lines of business deemed a “conflict of interest.” That would mean Amazon could no longer run its marketplace for third-party sellers while also competing against them with its own products. Similar divestments would be required of the other top tech firms, and all could face massive daily fines for noncompliance.

Jayapal, vice chair of the House’s antitrust subcommittee, said the big tech companies cannot be trusted to police themselves, and that even beefed-up federal regulation may be insufficient, making forced breakups a necessity.

“Look, this isn’t about Amazon. This is about the monopoly powers of the Big Four tech companies,” Jayapal said in an interview. “It’s an irresistible urge for companies that are operating on multiple platforms with conflicts of interest and competing business to use power in ways that will suppress competition.”

She also cited the dominance of advertising platforms Google and Facebook, which have gobbled up most online ad revenue, hastening the decline of newspapers and other local news outlets.

Amazon surpassed Boeing last year to become Washington’s largest private employer, as the online retailer set sales records and went on a hiring jag as the coronavirus pandemic shut down many retail stores. The company ended 2020 with more than 80,000 employees in the state, a 25% increase over the previous year.

Despite its huge role in the local economy, and provision of many highly paid technical jobs, Amazon long ago ceased to be viewed simply as a hometown employer. The company has faced fierce criticism and even hostility from some Seattle leaders and activists for its treatment of workers and impacts on housing affordability.

The focus on today’s ubiquitous big tech giants in some ways echoes past antitrust confrontations in the U.S. In the 1980s, the federal government forced the breakup of the Bell System phone monopoly. In the late 1990s, the U.S. sought to bust up Microsoft over its PC market stranglehold — a battle that ended in a 2002 settlement curbing some of its practices.

The Big Four have inspired blowback from across the political spectrum, though not always for the same reasons. All five of the House bills rolled out last week had both Democratic and Republican co-sponsors — producing some unusual alliances.

Jayapal, a Democrat first elected in 2016, chairs the Congressional Progressive Caucus. Her bill is co-sponsored by Texas Republican Rep. Lance Gooden, a conservative elected in 2018 who pledges to fight “growing calls for socialism in America.” Gooden represents a conservative Dallas-area district where 61% of voters backed Donald Trump last year, compared with just 12% in Jayapal’s Seattle-area district.

In a recent Fox News interview, Gooden said companies like Amazon and Facebook “have no respect” for a free marketplace. “They want to control thought. They want to control speech. They want to control product placement. They actually market their ability to control search engine results and to direct traffic online,” he said.

Amazon’s executives have defended its practices amid the antitrust push, arguing efforts to break it up or otherwise regulate its massively popular platforms would ultimately harm consumers and small businesses.

Asked for comment about Jayapal sponsoring a bill to break up the Seattle-headquartered company, Jack Evans, an Amazon spokesperson, said in an email, “we have not commented on the legislation and will decline comment on Rep. Jayapal’s role.”

However, in a blog post last fall responding to the House antitrust report, Amazon criticized its “fringe notions” and said “misguided interventions in the free market would kill off independent retailers and punish consumers by forcing small businesses out of popular online stores, raising prices, and reducing consumer choice and convenience.”

While millions of third-party sellers benefit from selling on Amazon’s marketplace platform, some have come to view it as a deal with the devil, saying the company squeezes them — and drives up prices for competitors — by controlling virtually every aspect of e-commerce transactions.

Bernie Thompson, the founder of Redmond-based Plugable Technologies, which sells laptop docking stations and other electronics, said he relies on Amazon’s platform for more than 85% of his company’s sales.

Thompson said Amazon has built a “brilliant model” that invites competitors to access its platform and unparalleled customer base. “But they also advantage themselves at every level. Having a fair and level playing field has never been one of Amazon’s values or focuses,” he said.

He welcomes the heightened scrutiny of Amazon’s practices by Congress. While there are risks to government regulation, he said, there are also “enormous risks to a marketplace where the biggest entities are above competitive pressures.”

Last month, the attorney general for the District of Columbia, Karl Racine, filed an antitrust lawsuit against Amazon, alleging the company’s practices cause “artificially high” prices in e-commerce sales.

Amazon also has been accused of tapping its massive trove of sales data to target and undercut third-party sellers, in some cases by essentially copying their popular products and selling them at a lower price.

The company has long denied that it misuses third-party seller data in that manner. An Amazon attorney said at a congressional hearing in 2019 that “we don’t use individual seller data” to compete with other businesses on its platform.

But the Wall Street Journal reported last year that Amazon employees had used such data to launch and benefit its own products, citing interviews with more than 20 former employees.

Jayapal questioned Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos about that report at a congressional hearing last year. Bezos said the company has a policy against such data use, and was looking into whether employees had systematically violated it.

Jason Boyce says he experienced Amazon’s tactics personally. He had run a successful third-party seller operation starting in 2003, becoming a major seller of sporting goods.

“I used to be Amazon’s biggest proponent, cheerleader, fan,” Boyce said, describing his view now as “Love hate. Mostly hate.”

Amazon undercut his business, which was based for several years in Sammamish, Boyce said, by homing in on his successful products and offering identical or nearly identical versions at a discount. Eventually he sold his company and started Avenue7Media, which advises other merchants on how to navigate Amazon’s system and protect themselves.

Boyce said Amazon continues to disrupt third-party sellers with tactics such as making it more difficult to locate and click “buy” on disfavored merchants’ listings — a huge disadvantage when impatient shoppers are comparing online products.

“It’s incredibly insidious,” he said.

Boyce, whose testimony was cited in the House antitrust investigation, said government intervention is overdue: “Either a breakup or very thick guard rails” to protect competition.

Amazon has defended itself from such criticism, saying its groundbreaking decision to welcome third-party sellers to its platform in 1999 has continued to benefit consumers, and third-party sellers, as well as the company.

In its blog post last year, the company argued separating the third-party sellers from appearing alongside Amazon’s products “would revive, via the failed two-store model that Amazon tried two decades ago; the model that both small sellers and customers rejected.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce also has criticized the suite of House proposals, including Jayapal’s, for singling out the Big Four corporations.

“Bills that target specific companies, instead of focusing on business practices, are simply bad policy and are fundamentally unfair and could be ruled unconstitutional,” said Neil Bradley, the chamber’s executive vice president and chief policy officer, in a recent statement.

Mark McCarthy, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who has tracked the big tech debate, said there are pluses and minuses to the antitrust approaches outlined in the legislation proposed by Jayapal and others. Forcing the separation of Amazon and its third-party marketplace could yield some negative impacts, he said.

“There are consequences for this that might not be all that good for consumers and merchants,” he said, saying shoppers would have a harder time finding products and sellers might lose out on customers.

McCarthy pointed to another antitrust bill introduced by Rep. David Cicilline, D-R.I., that would not divide up tech companies but would prohibit “discriminatory conduct” by “dominant platforms” and make it illegal for Amazon to use nonpublic data obtained on third-party sellers’ products.

Doing nothing, McCarthy said, is not an option.

“This is the kind of conversation we need to have about how best to deal with the enormous power that these companies have. I am glad it’s out there.”

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.