By Anna Orso

The Philadelphia Inquirer

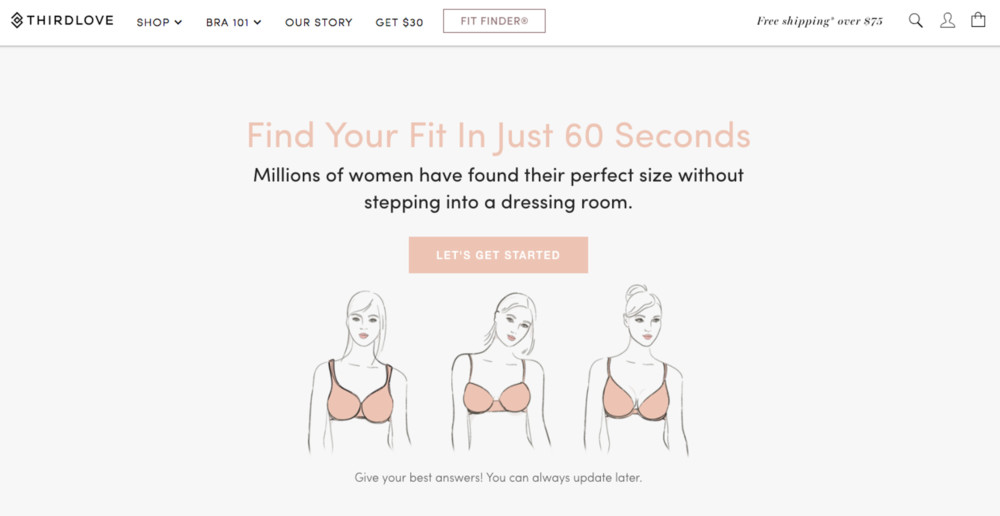

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Cora Harrington runs an intimate-apparel blog. She says start-up lingerie companies are emerging at a time when they can market to a generation of consumers used to online shopping, buyers who might not bat an eye at being fitted via online quiz.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Once Instagram and Facebook determine you’re a woman who might wear a bra from time to time, it’s all over for your timeline.

While men on social media are routinely treated to ads for sleek suits and financial products, many women see a whole lot of breasts.

The common ad experience is something like: bras, yoga pants, bras, swimsuits, bras.

Scroll through your feed, and you’ll find a new company promising to solve undergarment-related problems you likely didn’t know you had.

Knixwear advertises its 8-in-1 (!) “evolution bra.” LIVELY (all-caps, for some reason) says there’s “finally” a bralette for me! And there’s Stickee Bra, the company that claims, however dubiously, that bras with underwires might cause cancer.

Some of these companies have detailed fit guides on their websites, while others, like ThirdLove and True&Co., offer the perfect-fitting bra for an average of $45 to $70 after customers take a quiz and give up their breast-related data.

Traditionalists say this process could never deliver on these promises because it’s lacking face-to-face interaction with a trained professional. But these online companies swear by virtual bra fittings, a process that millions of women have embraced, and that some say could eat into sales at brick-and-mortar stores.

“We’re a pretty substantial player,” said ThirdLove cofounder Heidi Zak, “known as the brand to take down Victoria’s Secret.”

Meanwhile, the lingerie giant’s in-store sales are slipping, and some analysts say confidence in its market domination is decreasing.

Some blame the rise of e-commerce and the fall of shopping malls. Others say Victoria’s Secret has failed to adapt to changing attitudes about size inclusivity and body image, giving up ground to Aerie, American Eagle’s lingerie offshoot that doesn’t digitally alter its ads.

A recent analysis even suggested Victoria’s Secret, founded in 1977 and often associated with the world’s most recognizable supermodels, may take a hit in the post-MeToo era while the country grapples with how society sexualizes women.

“People are tired of Victoria’s Secret,” said Cora Harrington, who runs an intimate-apparel blog. “They want alternatives and options. They want companies more connected to their values. These start-ups, in terms of their marketing, are speaking to that.”

Harrington, whose book In Intimate Detail will be released in August, said start-up lingerie companies are emerging at a time when they can market to a generation of consumers used to online shopping, buyers who might not bat an eye at being fitted via online quiz.

ThirdLove’s FitFinder asks users about the bra they’re currently wearing: What size it is, what brand it is, where the band falls, how tight the straps are, and how their breasts sit in the cups. It also asks women to identify their breast “shape,” whether it’s “asymmetric,” “athletic,” “teardrop,” or “east-west” (breasts that point outward).

The algorithm does its magic, and then provides the customer with her results: a band size, a cup size, which come in half-sizes, like D 1/2 and a bra-style recommendation.

Zak, a former Google employee who cofounded ThirdLove in 2013, which turned into one of the country’s fastest-growing companies, said she’s constantly thinking about variations ThirdLove can add to its arsenal of more than 70 sizes.

She said the FitFinder is based on the expertise of professional bra fitters, who can in many cases look at a woman, examine how her current bra fits, and recommend a size.

“When you have as many women as we do come through and use it, you can likely get a better prediction because of the sheer breadth of data we have,” she said. “Imagine if one bra fitter fit 10 million women.”

Tracy Gallagher is a 29-year-old bra fitter at Hope Chest, a Center City lingerie boutique, who uses a measuring tape but can often determine bra size just by looking. She says the most common bra mistake women make is that they wear a band that’s too large for them, easy to tell when you know what to look for, Gallagher said: a band that rides up in the back, gaping cups, and slipping straps.

If you take a quiz and order a bra online, Gallagher said, you still might not be able to tell if it fits correctly, saying women usually need a second set of eyes.

True&Co. CEO Michelle Lam said there are benefits to being fitted in-person. She said her company’s “Fit Quiz” is meant to provide an at-home alternative for women who don’t feel comfortable going to a traditional fitting room.

LIVELY founder Michelle Cordeiro Grant said her company has a detailed fit guide that shows eight women and body types. The company tells buyers “the bedroom mirror” is the only way to tell if the bra fits once it arrives in the mail.

If it doesn’t? Shipping is free, and so are returns.

Julia Tackett, a 30-year-old freelancer who lives in South Philadelphia, sees bra ads on Facebook and Instagram constantly.

She recently broke down and ordered a couple of LIVELY’s Busty Bralettes, one of the company’s best-selling items.

The $35 bralette comes in two sizes, 1 and 2, the latter serving women with larger breast sizes. Tackett ordered a size 2, and it still felt too small. She ended up keeping the bras until they stretched enough that they sort of fit, but she said she probably wouldn’t order from LIVELY again.

But she’s not done trying. Tackett, who for many years shopped for bras at an independent boutique, might try ThirdLove next. She’s drawn to its large range of sizes, and is interested in trying an underwire version “of this new technology branding Facebook keeps throwing at me.”

“Maybe they have found some kind of technology I’m not hip to yet,” she said.

Harrington said online “fitting” has potential, where it really succeeds, she said, is in getting women to think about their bra size, a revolution that began more than a decade ago when the idea that many women wear the wrong size bra entered the public consciousness.

But she worries companies with clever marketing take advantage of a lack of consumer education about lingerie and position themselves as the solution to problems that don’t exist.

“One thing a lot of these companies have is a level of PR savvy that most legacy brands don’t have or haven’t bothered investing in,” she said. “They have the marketing and the PR to position themselves as much more influential or more relevant to the total industry than perhaps their market share would indicate.”

Plenty of women on Instagram have noticed. Lauren Hallden, a 34-year-old tech designer who lives in Port Richmond, last fall wrote an open letter about endless lingerie ads on Instagram that’s since been read more than 200,000 times.

She said the bra ads on Instagram still haven’t gone away, though she flags them consistently and has never purchased one, and she doesn’t like seeing models invading the space she uses to look at photos of her friends’ kids and dogs.

“When the post went out, I started hearing from men like, ‘Oh, I get ads for boots and credit cards,’ and I was like, ‘Why are women only getting stuff about their bodies all the time?’ ” she said. “It’s so reductive.”

Zak, of ThirdLove, said she’s not sure women are seeing ads for lingerie more than anything else, perhaps, she suggested, those ads are simply more noticeable. Grant, of LIVELY, said the company’s website aims to highlight women of different shapes, sizes, and colors.

But she said its social presence is undoubtedly how the company reaches the most customers: “What bigger billboard in the world is there than Instagram?”