By Heidi Stevens

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Chanel Miller was sexually assaulted by Brock Turner at Stanford University in 2015. Until the release of her recent book “Know My Name: A Memoir,” Miller was simply known as “Emily Doe.”

Chicago Tribune

While she wrote “Know My Name: A Memoir,” Chanel Miller would take breaks to draw.

“As a way of letting my mind breathe,” she writes, “reminding myself that life is playful and imaginative.”

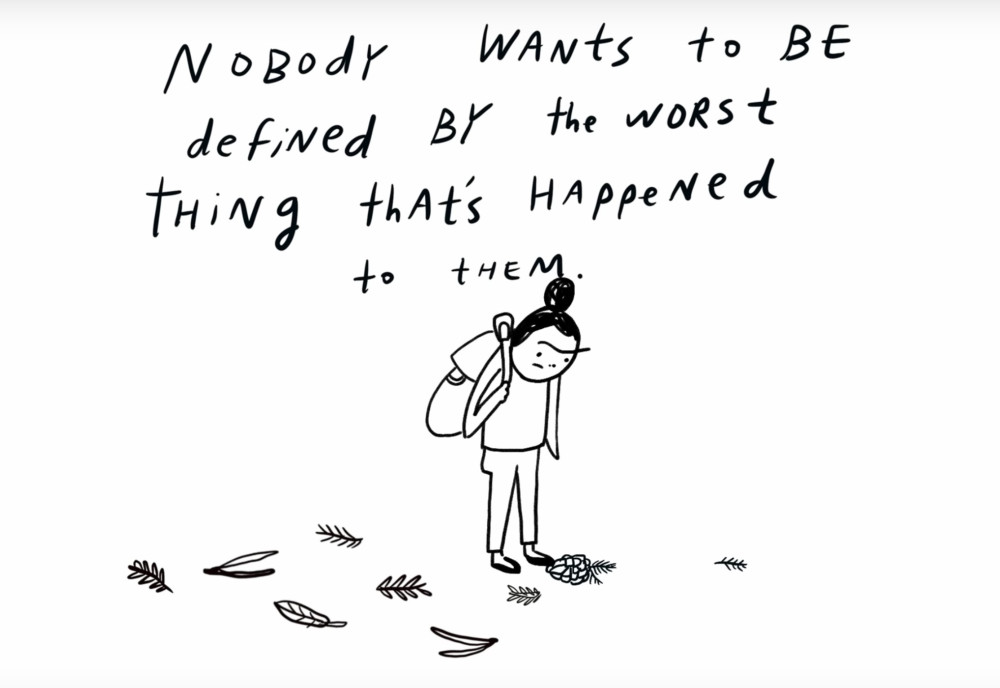

She made her drawings into a short film called “I Am With You.” It’s five minutes long. If you let it, it will stay with you for an eternity. The spare black-and-white line drawings, the harsh truth of her words. The courage to put them out into the world.

“Assault teaches you to shrink,” Miller narrates, “makes you afraid to exist. Shame, really, can kill you.”

Miller was sexually assaulted by Brock Turner in 2015 at Stanford University. She was known to the world as Emily Doe until September, when she announced she had written “Know My Name,” a memoir about the attack and its aftermath.

Her writing about the night she was sexually assaulted, starting with her 7,000-word victim impact statement, has been clear-eyed and potent.

“I had multiple swabs inserted into my vagina and anus, needles for shots, pills, had a Nikon pointed right into my spread legs,” she wrote in her statement, which she read from in court. “I had long, pointed beaks inside me and had my vagina smeared with cold, blue paint to check for abrasions.”

She described showering after the exam.

“I stood there examining my body beneath the stream of water and decided, I don’t want my body anymore,” she wrote. “I was terrified of it. I didn’t know what had been in it, if it had been contaminated, who had touched it. I wanted to take off my body like a jacket and leave it at the hospital with everything else.”

In Viking Books’ Instagram announcement of her book release, Miller wrote this:

“You will find society asking you for the happy ending, saying come back when you’re better, when what you say can make us feel good, when you have something more uplifting, affirming. This ugliness was something I never asked for, it was dropped on me, and for a long time I was worried it made me ugly too. But when I wrote the ugly and painful parts into a statement, an incredible thing happened. The world did not plug up its ears, it opened itself to me.”

The short film feels less like a linear narrative and more like a glimpse inside Miller’s head as she processes the trauma and shock and slow healing of the last four years.

The words “unconscious,” “stupid,” “swimmer,” “dumpster,” “Stanford,” “half naked,” “nameless” and “nobody” fill Miller’s mind and our screen.

“Nobody wants to be defined by the worst thing that’s happened to them,” she narrates.

One of the things I love about the film is that it lets us into another layer of who Miller is, separate and apart from what happened to her. She’s an artist. She draws. She makes art to help make sense of the world. To improve the world, ideally.

“We all deserve a chance to define ourselves, shape our identities, and tell our stories,” Miller wrote in the description of the film. “The film crew that worked on this piece was almost all women. Feeling their support and creating together was immensely healing.

“We should all be creating space for survivors to speak their truths and express themselves freely,” she continued. “When society nourishes instead of blames, books are written, art is made, and the world is a little better for it.”

___

Join the Heidi Stevens Balancing Act Facebook group, where she continues the conversation around her columns and hosts occasional live chats.

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.