By Sandi Doughton

The Seattle Times

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) As Sandi Doughton reports, “a small Seattle startup is hoping to boost the performance of cloth masks with a spray coating that uses minute electrical charges to capture viral particles and prevent them from passing through the fibers.”

Seattle

Cloth masks may be one of our best lines of defense against the novel coronavirus, but they’re far from perfect. Compared to gold-standard N95 respirators, fabric face coverings aren’t as good at filtering out the tiniest droplets and aerosols that can carry the pathogen from one person to another.

But a small Seattle startup is hoping to boost the performance of cloth masks with a spray coating that uses minute electrical charges to capture viral particles and prevent them from passing through the fibers.

The approach hasn’t been thoroughly vetted and some mask experts are skeptical, but the National Science Foundation (NSF) was intrigued enough to give the company a $256,000 grant for initial development and testing.

“Our goal, for the average person who’s using a cotton mask, is to make that mask more effective and to make it safer so they’re less likely to contract the virus,” said Greg Newbloom, founder and CEO of Membrion, Inc.

Newbloom and his team envision packaging their product in spritz bottles people can use to treat their own masks. The coating would probably need to be replenished daily, at a target cost of $1 per application, he said last week at the Membrion lab in Seattle’s Interbay neighborhood.

Until recently, the University of Washington spinoff with a staff of 14 has specialized in flexible, silica gel membranes used in water treatment and purification. Now, about a third of its effort is directed toward face masks.

The firm has yet to turn a profit but has raised $7.5 million in investment funding and $3 million more in research grants. The membranes it produces are electrically charged to help pull pollutants out of industrial wastewater or create fresh water through desalination. The mask project was inspired early in the pandemic when Newbloom’s mother asked if the membranes could be used to filter the new coronavirus out of the air.

“I said: ‘Of course not, that’s not how they work,'” Newbloom recalled.

But then he realized the technology might be applicable to face masks, where the idea of using electrical charges to improve performance has a long history.

One thing that makes N95 masks so effective is an electrostatic charge imparted during manufacturing, said Peter Tsai, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, materials scientist who invented techniques to both produce the synthetic mesh material and electrify it. The charge makes the filter 10 times better at blocking viruses and other particles thanks to the kind of electrostatic attraction that causes a balloon to stick to your hair, said Tsai, who came out of retirement when the pandemic hit to help develop methods to sterilize N95 masks for reuse in hospitals without degrading the electrostatic charge.

He’s also been fielding proposals from researchers around the world with ideas for improving masks — few of which are likely to work, he cautioned. It’s especially hard to impart long-lasting electrical charges to fabrics like cotton, Tsai said.

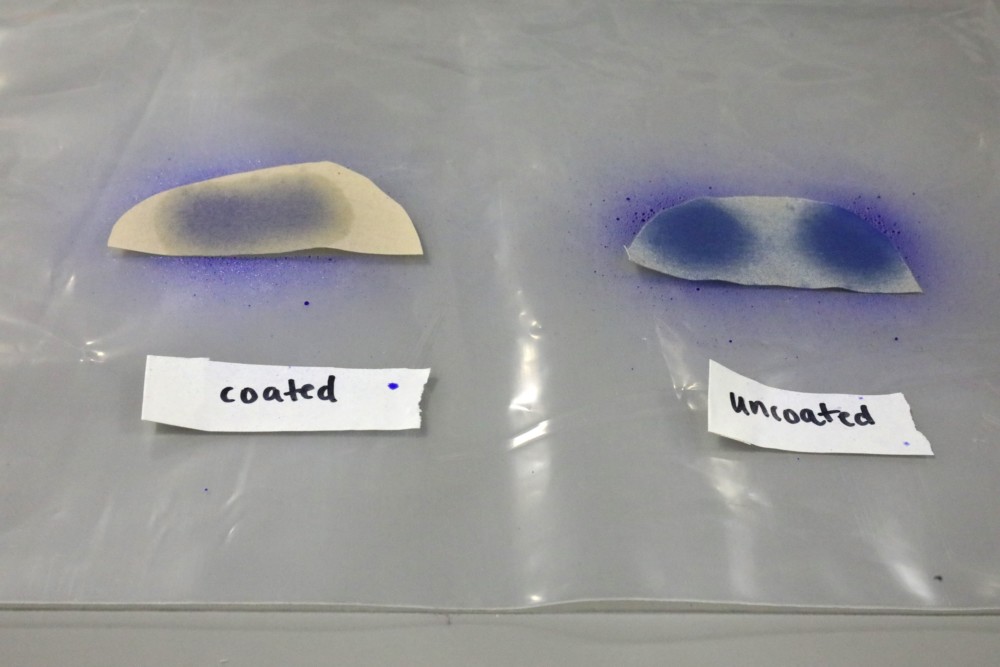

Membrion’s approach relies on microscopic, positively charged ceramic particles dissolved in alcohol. When sprayed on fabric, the alcohol quickly dissolves, leaving a surface coating of particles. Because the novel coronavirus carries a slight negative charge, it should “stick” to the positively charged particles.

Testing is still underway to see how well the spray works, and Newbloom declined to provide any preliminary data. One review of Membrion’s NSF grant application noted that “even if the coating gives a 10-20% increase in protection, this is significant.”

Simple cloth masks, if widely used, can reduce transmission of the novel coronavirus by about 40%, according to a recent analysis by the UW’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME).

IHME’s modelers also estimate the death toll from COVID-19 in the U.S. could exceed 500,000 by the end of February — but that nearly 130,000 of those lives could be saved if 95% of Americans wear masks regularly.

Because they’re very good at blocking exhaled respiratory droplets, masks are most effective when worn by infected people — either with or without symptoms. Masks also help protect wearers from inhaling larger, virus-containing droplets and aerosols exhaled by people who don’t wear masks, but tinier ones can slip through.

“If we all just wore masks, we probably wouldn’t need this product,” Newbloom said.

Steven Rogak, a professor of engineering at the University of British Columbia who studies aerosols, said Membrion’s technology sounds plausible — but it’s impossible to evaluate without data. He’s dubious of the commercial appeal, though.

A dollar a day is expensive compared to the cost of a mask, he pointed out. Now that N95 and Chinese-made KN95 masks are more widely available, it might make more sense for people to buy a few of those, letting them dry out between uses to preserve effectiveness, Rogak said.

But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health agencies still say N95 and other medical-grade masks should be reserved for health care workers. And with the virus starting to surge again, new shortages are possible.

Rogak and his colleagues recently tested a wide range of common mask materials for filtering power and breathability. (Double-knit cotton and dried baby wipes were winners for DIY masks.) But how well a mask fits can be even more important than what it’s made of — or whether it has an electrical charge, he said.

“A lousy-fitting mask is like insulating your house and leaving the windows open,” he said. “And this spray is not going to do anything to stop that leakage.”

Newbloom said his company is interested in partnering with mask manufacturers and employers who are looking for ways to better protect front-line workers. With several vaccines in the works, it’s not clear how long mask-wearing will be part of everyday life in the U.S., but there could be a market for Membrion’s spray in Asian countries where mask-wearing is more common, he added.

The treatment could also be tailored to target different viruses in the future.

The company expects to have effectiveness data within the next six weeks, along with a better understanding of how long the treatment lasts. It plans to hire an outside lab to verify its results, which will also include a safety analysis, Newbloom said.

Because the spray is not a medical device and contains well-known, nontoxic materials, no regulatory approval would be needed, he said. The exact chemistry of the solution is proprietary and the company has filed a patent application.

Making the spray isn’t complicated, and the company’s Seattle lab could produce up to 25,000 doses a day. But larger-scale production would require a partner.

In the meantime, Newbloom and his colleagues plan to start treating their own face masks with the spray if the early data is promising.

“Our team has agreed that if we all feel this is safe and effective, we’re going to be the first ones utilizing it before it goes out to the public,” Newbloom said.

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.