By Danielle Braff

Chicago Tribune

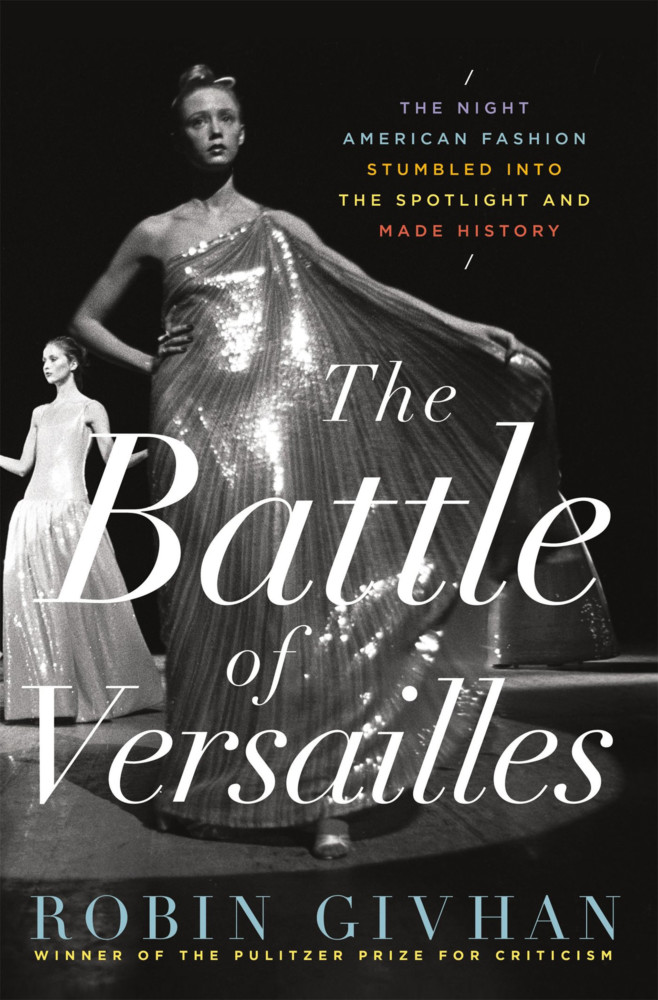

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Robin Givhan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post fashion critic talks about her new book, “The Battle of Versailles,” which focuses on a 1973 fashion show in Versailles, France, that included five American designers and 10 black models. When 10 out of the 36 models were black, it was the first time there had been so many black models on a runway at one time. A pivotal point for American fashion.

Chicago Tribune

Robin Givhan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post fashion critic, was all business as she spoke to a crowd of fashion enthusiasts recently during the Chicago Humanities Festival.

Fashion is always deeper than clothing, said Givhan, perched on a chair dressed in a dark sleeveless dress and conservative strappy black shoes by Dries Van Noten (a Belgian designer who happened to create shoes with red bottoms a la Christian Louboutin), her hair pulled back into a messy bun that was falling into a ponytail.

Givhan’s talk was focused on her new book, “The Battle of Versailles,” but she touched on everything from the lack of racial diversity in the fashion world to politics because, well, how could she not?

She started by assuring the crowd of her admirers, most of whom were clad in black glasses that echoed her own, that she had no political ties.

But, “So many politicians have used their clothes as a kind of costume for the story they want their administration to tell,” Givhan said. “There is a small part of me that hopes that we will have a first gentleman, so I can call and ask, ‘Who made your tuxedo?'”

The answer probably would be someone with white skin, seeing that there are so few fashion designers at the moment who are not white, she said.

The reason for this isn’t so simple, but Givhan has a few ideas.

There’s a trickle-down effect to cutting arts funding in public schools, she said. Once the schools knocked out the arts classes, then the underprivileged students had few other outlets to learn about drawing and fashion.

If education about fashion isn’t happening in the schools, Givhan said, then black students won’t grow up to be black fashion designers.

Currently, she said, the percentage of black students at design schools is in the single digits. And the numbers are just as stark when it comes to black models.

“We have a lot of stories about the importance of diversity in sports, but I don’t think that we view fashion through that same lens,” Givhan said. “If we did, there would have been much greater outrage, because we could go through an entire fashion season and see 10 models of color on 200 runways.

The fact that there is less diversity on a fashion runway may not seem like a huge deal on the surface, but it’s a reflection of a greater problem in our culture today.

“If we are not represented by the fashion industry, which determines standards of beauty and what it means to be feminine, what it means to be masculine, then it means that there are whole segments of the population that are undervalued,” Givhan said.

She has spent her career dissecting the role of fashion on the runway, on politicians and in your closet, so while some may think that clothes are just clothes, she sees fashion as much more significant.

“In Robin’s hands, fashion is a lens to which to view the world,” said Gioia Diliberto, author of “Diane Von Furstenberg: A Life Unwrapped.” “Fashion is about character and personality, and it offers clues.”

Those clues are laid out clearly in “The Battle of Versailles,” when Givhan describes how a 1973 fashion show in Versailles, France, that included five American designers, Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, Anne Klein, Halston and Stephen Burrows, five French designers and 10 black models was a pivotal point for American fashion.

During her talk, Givhan explained that on that night, when 10 out of the 36 models were black, it was the first time there had been so many black models on a runway at one time.

“At least three designers had to agree to use a particular model,” Givhan said. “These models came of age at a time when the culture was thinking about race relations.”

Advertisers and designers were looking for black models, and society was hoping that racial harmony could be achieved by using black models in line with white models.

It was also a time when individuality was celebrated, when fashion designers were letting the models do their own thing on the runway rather than having a monotonous feel to their shows.

“They were three-dimensional characters,” she said.

This changed in the 1990s, when designers were interested in having a much more homogenous look.

They wanted models who looked the same, had the same hair and makeup, and walked the same, so that the clothing would shine rather than the models.

“What was celebrated at Versailles was not so much the beauty of the black models, but it was the idea of personality and individuality,” Givhan said. “When fashion stopped celebrating individuality, they stopped celebrating diversity.”

And the celebration never recovered.