By Thomas Lee

San Francisco Chronicle

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) It has been a tough couple of months for both Theranos and Zenefits. There has been plenty of criticism of the two companies, both former darlings of silicon valley which ran afoul of regulators. However Zenefits CEO David Sacks is quick to point out that in comparing the two many have ignored the differences in each company’s approach towards transparency and remediation.

San Francisco Chronicle

If you need a surefire way to annoy Zenefits CEO David Sacks, just lump his company in with Theranos.

On the surface, the two companies share some similarities: Both firms were unicorns, worth more than $1 billion on paper, that eventually ran afoul of regulators.

Zenefits, based in San Francisco, makes human resources software that it gives away to companies who purchase health insurance through it. Theranos, based in Palo Alto, is developing technology it says can diagnose multiple diseases with just a few drops of blood.

But that’s where the comparisons end. Zenefits moved quickly to accept responsibility after disclosing that its employees were selling insurance without proper licenses. Founder Parker Conrad resigned as CEO, replaced by Sacks. Over the following weeks, the company expanded its board of directors, recruited a chief compliance officer, commissioned an audit from a big accounting firm, and reached out to state insurance regulators.

Theranos just hired a chief compliance officer, in what could easily seem like a me-too move. But it has otherwise remained defiant about allegations that the company misled investors and regulators about whether its technology actually works.

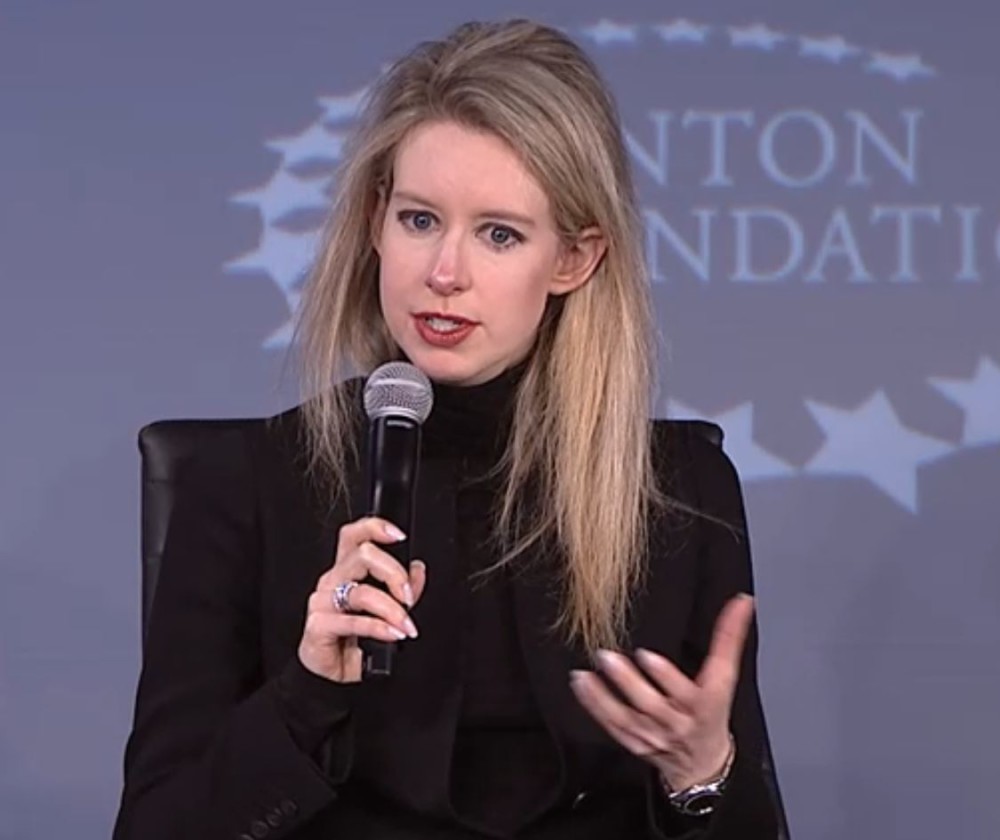

Founder Elizabeth Holmes remains CEO even as the company faces a federal criminal investigation and a probe by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Last week’s move came nine months after the allegations first rocked the company.

“People who made easy comparisons (between Theranos and Zenefits) ignored the differences in our approach toward transparency and remediation,” Sacks told me in an exclusive interview.

For example, Sacks says he is optimistic that Zenefits will resolve its issues with state regulators because the company has been forthright about went wrong and how it fixed those problems. Zenefits did lose one big account, e-commerce startup Jet.com, but has retained most of its customers.

Meanwhile, the bad news continues to pile up for Theranos. Walgreens ended its partnership with the company, the primary way Theranos reached consumers with its blood tests, and regulators recently revoked Theranos’ license and banned Holmes from operating testing laboratories. (That penalty is pending and Theranos can appeal.)

Both companies made big, avoidable mistakes. Zenefits was generating big insurance commissions while allowing employees to cheat on licensing exams using a software tool Conrad himself had ginned up. Worried that competitors might copy its technology, Theranos clouded its tests in secrecy and did not reach out to the scientific community for independent validation or seek out board members with strong technical qualifications.

“It doesn’t matter what product or service you are trying to bring to the market,” said Johanne Bouchard, who advises boards and entrepreneurs on corporate governance and leadership issues. “It is so important to be proactive and avoid having to react, particularly at the board level. You need the the infrastructure in place from the beginning to ensure the company’s success,” especially in highly regulated markets like insurance and medical devices.

But Zenefits and Theranos responded to adversity in remarkedly different ways.

From the get-go, Sacks had Zenefits fall on the sword.

“We must admit that the problem goes much deeper than just process,” he wrote in memo to employees. “Our culture and tone have been inappropriate for a highly regulated company.”

Sacks said Zenefits needed to accept the consequences of its mistakes in order to move forward as a business.

“We hired a chief compliance officer on my first day as CEO,” Sacks told me. “But we’ve gone much further than that. Over the past six months, we’ve effectively refounded the company with a new set of values and culture.”

By contrast, Holmes did not offer any regret or contrition. She did not even seem to grasp the severity of Theranos’ predicament. Her actions suggested she was chalking it up as a public relations problem.

Holmes hired Brooke Buchanan, a former top aide to Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., to oversee communications. But Theranos’ PR strategy seemed disjointed and confused. Holmes went on “Today” and said she was “devastated” by the problems and thought that the things regulators pointed out had been fixed. She planned to host a press conference with 200 members of the national media after presenting to the American Association for Clinical Chemistry’s annual conference next month in Philadelphia. Theranos then decided to cancel the press conference, and Buchanan recently left the company.

To Holmes’ credit, the company has since hired people who boast impressive resumes. Dave Wurtz, vice president of regulatory and quality, was a former top executive at ThermoFisher Scientific, where he regularly dealt with the Food and Drug Administration.

Chief Compliance Officer Daniel Guggenheim was assistant general counsel of regulatory law at McKesson Corp., one of the country’s largest health care firms.

Theranos must translate those moves into real transparency and accountability, Bouchard said.

Sacks agreed.

“The hallmark of our approach is to be extremely transparent about what went wrong,” he said. “This has allowed us to fix problems quickly and rebuild trust with regulators.”