By Tim Henderson

Stateline.org

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) In Chamblee, a city shared by professionals commuting to Atlanta and immigrants working locally, women make more than the typical Atlanta metro worker, but men make far less.

CHAMBLEE, Ga.

This Atlanta suburb is a lot like other metropolitan suburbs around the country. A manufacturing economy is giving way to new apartments and tech enterprises built around a quick commute to Atlanta.

And as in other communities, there’s a measurable pay gap between its working men and women. But there’s something different about Chamblee: Here it’s the women who earn the higher wages, typically $1.37 for every dollar brought home by a man.

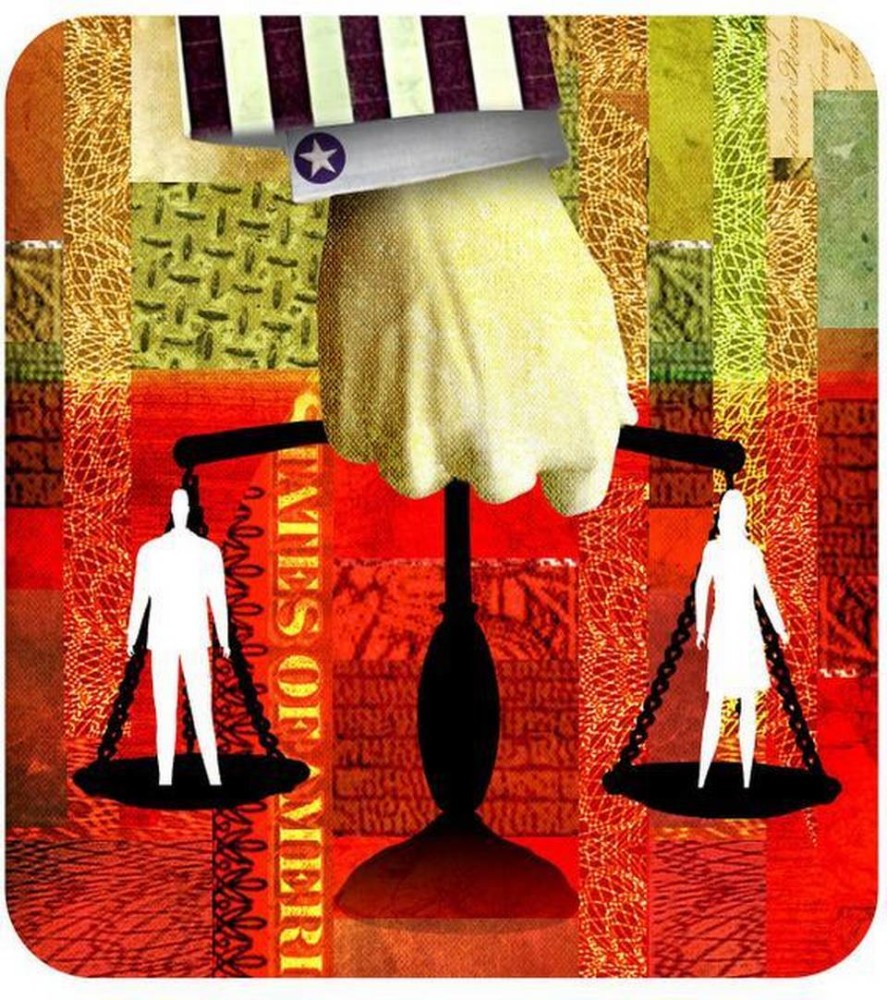

That’s astonishing in a country where, nearly universally and in nearly all of the 2,700 locations reviewed by Stateline, men earn more than women. Nationally, the pay gap is wide: Women still earn less than 80 cents for every dollar men take home.

Of the 2,700 locations in the United States with more than 10,000 workers, Stateline found, there are just six municipalities and one county that flip the script in a statistically significant way.

A Stateline review of census data on earnings across the country found that women also make more in Lake Worth, Florida; the cities of Plainfield and Trenton in New Jersey; Inglewood, California; the village of Hempstead on Long Island, New York; and the Washington, D.C., suburb of Prince George’s County, Maryland.

Most are diverse suburbs in large metro areas. All are majority-minority, and many have low-income neighborhoods as well as the economic benefits of proximity to vibrant cities.

The reasons for the pay differences are complex and uncertain: Pay may be relatively higher for young millennial women who have landed jobs in big cities and found affordable housing in commuter suburbs such as these. And the communities’ high numbers of single male laborers, many of whom are immigrants working without documentation, can also hold down male income, which makes female income relatively higher.

But there are also some hopeful signs for all women in these places: Women in Chamblee, for instance, earn more than women in the Atlanta area as a whole, and out-earn men in some lucrative, male-dominated fields, such as computers and engineering, with the help of female business entrepreneurs sensitive to the need for flexibility to attend to family responsibilities.

In Chamblee, one of those women is Lindsey Cambardella, an attorney who grew up in the area and yearned to run a business.

buy kamagra polo generic buy kamagra polo online no prescription

She applied last year for her dream job, running a national language interpretation and translation firm. She was married, in her 30s, with no kids, and worried about that impression.

“I was very up front,” Cambardella recalled recently. “I said, ‘I’m planning to have children _ and soon. I don’t want you to have any surprises.'”

Fortunately, the business owner was also a woman, one who had built the firm up by herself over 20 years after a career in sales and state government, while also raising a son.

“She immediately shot back: ‘That doesn’t scare me at all,'” Cambardella, 34, recalled. “I think I was lucky in that she was open-minded and not worried about it.”

Cambardella now makes more than her husband, an urban landscape architect who took a step down in pay recently to take a job with the city of Atlanta.

Claudia Goldin, a Harvard University economist, argued in a 2015 paper that more flexible hours would go a long way toward solving the gender pay gap, which she said is often caused in part by women working fewer hours and stopping work at times, often to raise children.

That’s one reason Shear Structural, an engineering firm started by three women in Chamblee, prioritizes flexibility, said co-founder Malory Atkinson.

“They say a lot more women study STEM fields than actually end up working in it,” she said, “so we’re very cognizant of that, and we do whatever it takes to be accommodating.”

The gender pay gap is especially wide for women with children and women who are married (because employers suspect they will have children). Men, by contrast, tend to get paid more after marriage based on the assumption it will make them more ambitious.

“Marriage adds a premium to a man’s income, and it’s a drag on women’s income,” said Ariane Hegewisch, study director for the Institute for Women’s Policy Research in Washington.

More Men in Low-Paying Jobs

But the reason women make more than men in the seven places on Stateline’s list is not entirely a reflection of their own success. Many of the places on the list have low-wage male workers, often unauthorized immigrants, and that alone can bring down the median male wage to a point where it is lower than that of women.

“All low-paying jobs have similar pay for all,” Goldin said. “If everyone got the minimum wage, then the gaps would disappear.”

In Chamblee, a city shared by professionals commuting to Atlanta and immigrants working locally, women make more than the typical Atlanta metro worker, but men make far less.

Yet even in this town, the gender pay gap that exists between people working in the same professions still tends to favor men.

A majority of Chamblee’s female employees work in management, science and arts jobs, where their typical pay is about $57,000, less than men working in the same fields. Women make more than men in the city as a whole, across professions, because immigrant men working in low-paying service or labor jobs bring down the median pay for men.

Chamblee has long been a destination for immigrants. The city has a dense housing district called “the Triangle” where Chinese and other Asian immigrants once lived and worked in nearby factories. Asian institutions and restaurants remain, and the name “Chinatown” is still on many facades, but most of the factories have closed, and the city’s immigrants are now mostly men from Latin America.

Most men in Chamblee work in service jobs, construction, factories or moving and shipping jobs, where they typically earn $20,000 to $25,000 a year, the equivalent of $10 to $12 an hour.

Census data shows that Chamblee’s immigrants are mostly from Mexico and Guatemala, and those who are not citizens are predominantly men, by a nearly 2-1 ratio.

Those men typically arrive alone in their 20s, work for three to five years, and go back home to enjoy the money they’ve saved, said Julio Penaranda, who manages Plaza Fiesta, a Hispanic-themed shopping center in Chamblee.

“Their earning potential is very limited,” he said, “because these workers are unskilled and undocumented.”

Diversity and High Income

Another reason women might earn more than men in some predominantly black suburbs, like Prince George’s County along with Trenton, New Jersey, and Inglewood, California, is that black women tend to be better educated than black men, said Nicole Smith, chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce and co-author of the center’s 2018 report on the pay gap.

Prince George’s County has only a modest boost for women’s pay at 103.5 percent of men’s earnings. But it’s the only county on the list and by far the most populous area, with about 900,000 residents.

Tonia Wellons, 46, lives comfortably there, in a 3,200-square-foot home in Upper Marlboro. Wellons is a vice president at the Greater Washington Community Foundation, and has held high-ranking positions in the Peace Corps and at the World Bank.

She makes “a little more” than her husband, Lyndon Joseph, an electrician with his own home improvement business. They have four children, including one in college.

Wellons said many of her neighbors moved there from neighboring Washington, D.C., in search of a more serene setting to raise children. The county is known for its prosperous black community, it has by far the highest household income, about $76,000, of any majority-black county. The second is DeKalb County, Georgia, where Chamblee is located.

Some of the factors that stand out in Prince George’s County: a large minority population and a lot of people who work for the federal government, which has civil service rules that discourage discrimination in hiring and promotions.

Nationally the pay gap between black and Hispanic women and men of the same group is smaller than that between white women and white men, according to census data. White women earn 77 cents for every dollar earned by white men, and a gender gap exists across all racial groups.

Prince George’s has the third-most full-time federal workers, about 65,000, of any county in the nation, more than half of whom are women. Another 32,000 residents work for nonprofits, and two-thirds of them are women too, including Wellons.

The importance of federal and other government employment is clear, said several experts on pay inequity.

The fact that all seven places are majority-minority is harder to explain.

Race alone is not enough to explain why women make more in some majority-minority communities, Hegewisch of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research said.

“The few places with no gap or reverse gap do tend to be urban and majority-minority,” said Kevin Miller, senior researcher at American Association of University Women. “What’s happening there is that white men, the group with the most disproportionately high salaries, are more absent from those areas.”

Wellons has a theory about why racially diverse areas may see more equity in pay by gender.

“There’s more [racial] equity here. There really is. I can feel it,” she said. “Maybe racial equity encourages other kind of equity too.”

What Now?

Working to reduce the pay gap is an ongoing issue for women, even in those communities where overall they make more compared with men.

Wellons got her first lesson in pay discrimination in one of her first jobs out of graduate school 20 years ago. She learned that a male colleague with the same job and qualifications was making $7,000 a year more.

“Back then, that was significant. I was making $27,000 and he was making $34,000. So it was a lot,” Wellons said. She approached her bosses, who argued with her and threatened to invite others to apply for her job as a test of its market value, but she prevailed and got the raise.

In her career, she said, she’s also been surprised at the difference between male and female attitudes toward pay. At the World Bank, she spent years negotiating pay for new hires.

“Men always wanted to negotiate,” she said. “The women would just say, ‘Thank you.’ They were so happy to be offered fair pay.”

Women don’t negotiate for their own pay as aggressively as men, said Hegewisch, but that’s partly because they’re judged more harshly than men for doing so.

“When women do negotiate as assertively as men,” she said, “they do not get the same results.”

In Chamblee, Cambardella said she was surprised that a male family friend with a good job negotiated when he was offered a raise a few weeks ago.

“I would have just said ‘Thank you!'” she said. “He said, ‘Oh I have a different figure in mind.'”

Cherlee Rohling, a 28-year-old Chamblee resident who is engaged to be married, said she thinks the pay gap sometimes favors young women because they’ve had to work hard for the success they get. An operations manager for a manufacturer, she makes more than her fiance.

“Women have had to start working 10 times harder than men, and we don’t give up,” Rohling said. “I’m sure I make more than some men, but not because of youth, because I’m a hard worker.”