By Amanda Cuda

Connecticut Post, Bridgeport.

When Viagra was released in 1998, it set records for the most prescriptions written in a week.

Not so for the drug that some call the female Viagra.

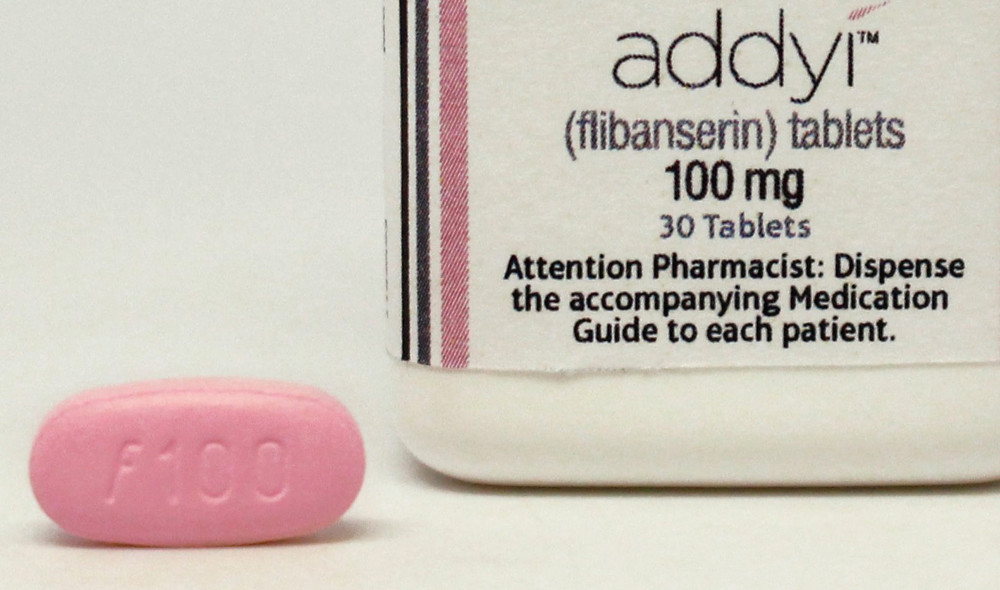

Addyi, the first drug approved to treat sexual dysfunction in women, went on sale last week and was met with health warnings from women’s groups and a big ho-hum from consumers.

“It has a lot of restrictions on it,” said Dr. Carol Fucigna, interim chairwoman of Stamford Hospital’s department of obstetrics and gynecology. “And I think once women are aware of all the restrictions, they’re less interested.”

There are few similarities between the new medication and the blue pill that’s been remedying erectile dysfunction in men for years, said Dr. Mary Jane Minkin, clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine.

Viagra works by increasing blood flow to the penis, triggering arousal. But Addyi’s intent is to increase sexual desire — an emotional result that can be difficult to pull off, and even tougher to measure, Minkin said.

“Libido is much more subtle than just getting an erection,” she said. “You’re not going to be able to see” the results.

That subtlety is one reason why Minkin and other experts think the medication won’t make as big a splash as Viagra did.

Then there is the fact that it must be taken every day and comes with a warning not to drink alcohol, which could be a turnoff for many women. It also isn’t supposed to be used by two groups of women who arguably need it the most — post-menopausal women and those on certain antidepressants.

In addition, the drug has some alarming potential side effects, including low blood pressure and prolonged unconsciousness.

The latter has caused some groups to issue fact sheets urging caution about the drug.

Yet despite its flaws, Addyi is a game-changer in that it represents a solid step forward in addressing a lack of libido in women, Minkin said.

“This is a victory for acknowledging that women should be treated as sexual human beings,” Minkin said.

A strange path

Addyi’s path to approval was a somewhat complicated one. For years, there was little, if anything, available for women suffering from low libido, also known as hypoactive sexual desire disorder, which affects up to one in 10 women.

Minkin said she tried a variety of medications with her patients, including testosterone, which can increase sex drive in some women. For those who had a sex drive but had trouble reaching orgasm, she sometimes prescribed Viagra, and said the increased blood flow it produced did help some women climax.

But there was no formal, Food and Drug Adminstration-approved medication for women until Addyi came along.

The drug, which has the medical name flibanserin, was originally created as an antidepressant by Boehringer Ingelheim, a German pharmaceutical company with offices in Ridgefield. Minkin said researchers eventually noticed that women taking the drug had an increase in sexual desire.

In 2009, Boehringer submitted the drug to the FDA for approval to treat hypoactive sexual desire disorder. The FDA rejected the application in 2010, stating that Boehringer “had not provided sufficient evidence of efficacy.”

Boehringer then sold the drug to Raleigh, N.C.-based Sprout Pharmaceuticals, which tried to get approval for the drug for four years and backed a massive public relations campaign — Even the Score, which claimed that sexism contributed to the lack of a female sex drug. The FDA finally gave the company the go-ahead in August. The drug went on sale Oct. 17.

Fucigna and Minkin are both licensed to prescribe the drug, but neither have written any prescriptions so far. There are no publicly available sales figures for Addyi’s first week on the market.

“I think it’s still too new at this point,” Fucigna said. However, she does expect at least some interest once women know there’s a drug available for them. “I think initially a lot of women may want to try it. They’ll think it’s Viagra for women. But it’s not.”

Risks and restrictions

One major concern about Addyi are the side effects associated with the drug, including severely low blood pressure and loss of consciousness. These risks are more severe when patients drink alcohol or take certain medications — mainly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors found in antidepressants like Lexapro or Zoloft.

Minkin said it’s particularly unfortunate that the risk of side effects is so high for women who take antidepressants, as those women typically have problems with libido. Another problem she sees is that the drug is only approved for use by pre-menopausal women, though doctors can prescribe it for post-menopausal women at their discretion.

Addyi’s potential pitfalls have already drawn heat from some groups. The National Women’s Health Network, for example, has released the fact sheet “Addyi — Top 10 Things to Know.” In addition to the side effects and restrictions, the sheet says the drug barely even works. It points out that “only about 10 to 12 percent of women in clinical trials benefited even minimally from taking Addyi. For this small subset of women, the minimal benefits of taking Addyi seemed to be felt by about eight weeks.”