By Samantha Masunaga

Los Angeles Times

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Dana Thomas, a journalist and author of “Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes.” says, “Zero waste is the goal, and you’re not hitting the zero waste targets if you’re overproducing.”

Los Angeles Times

Fast-fashion retailers became giants by quickly churning out fresh, low-priced styles that pull trend-seekers into stores.

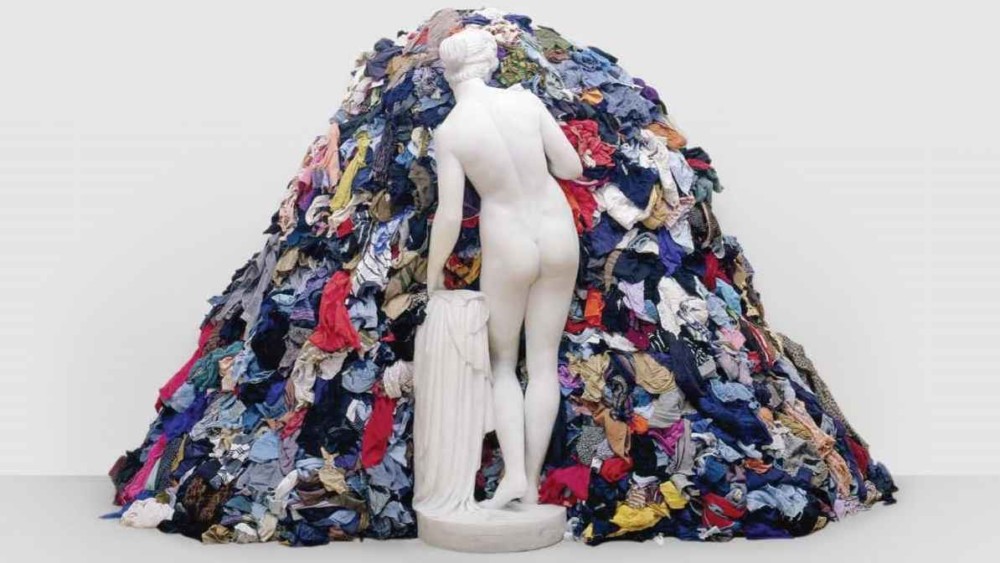

But that comes at a price. Rapidly producing clothes in large batches can save money, but if the items don’t all sell, that creates waste. Encouraging shoppers to buy as often as trends change means old clothes can end up in landfills.

Can fast fashion exist in a more sustainable world? The answer is complicated.

“If your business model is based on volume, that’s not what’s part of the sustainable movement in any industry,” said Dana Thomas, a journalist and author of “Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes.” “Zero waste is the goal, and you’re not hitting the zero waste targets if you’re overproducing.”

The clothing industry is responsible for about 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions and consumes more energy than aviation and shipping combined, according to the United Nations Environment Program. Every second, one trash truck’s worth of textiles is either burned or sent to a landfill, the U.N. said.

Fashion’s environmental problems stem from both the manufacturing process and overproduction — and they plague all levels of the industry.

Luxury clothing brand Stefano Ricci, which does not like to dilute its garments’ value by allowing discounts, told the Wall Street Journal last year that it regularly burns unsold products. Cartier owner Compagnie Financiere Richemont has bought back unsold watches and melted them down to be used in new designs. That recycles materials but still involves a double dose of manufacturing.

Swedish fast-fashion giant Hennes & Mauritz, better known as H&M, alarmed investors last year by reporting $4.3 billion of inventory on hand — an amount that had been creeping upward, indicating that it was producing more than it could sell. The company had to offer more discounts in order to get rid of the excess, and it couldn’t stop stocking up on new styles. It has since been working to claw its way out of that hole.

Customers are taking notice of the waste. Americans have increasingly expressed interest in buying sustainable goods, and sales data show they’re doing it.

Last year, U.S. shoppers spent $128.5 billion on sustainable versions of quick-selling goods such as groceries and toilet paper, according to a Nielsen survey. And 48% of Americans surveyed said they’d be willing to change their consumption habits to reduce their environmental impact.

Younger shoppers in particular are concerned about their effect on the environment. According to the Nielsen survey, 53% of those ages 21 through 34 said they’d give up a brand-name product in order to buy an environmentally friendly one, compared with 34% of those ages 50 through 64.

Brands won’t go green on their own, said Natan Reddy, senior intelligence analyst at data analysis firm CB Insights. “I do think that a lot of sustainability … is going to be driven by consumer demand,” he said.

Luxury fashion company Burberry used to destroy its unsold merchandise, getting rid of $38 million worth during its financial year ending in March 2018. Investors questioned the practice last year during Burberry’s annual meeting, according to Bloomberg. Two months later, the company announced it would stop destroying products. Instead, it donates or recycles the items and tries harder to make only as much as people will buy.

Shoppers, meanwhile, are turning to clothing sellers that don’t manufacture at all: secondhand dealers. Online marketplaces ThredUp Inc. and Poshmark, both based in the Bay Area, have become popular in the decade or so since they were founded.

People use the sites to offload their unwanted — but still fashionable — clothes, and buyers snap up those same clothes, spending less than the original retail prices.

ThredUp says it receives 100,000 items of women’s and children’s clothing a day. Sellers fill up a bag with used garments and send it to ThredUp. The company assesses the items and buys the ones it wants, then lists them for sale on its online marketplace.

The site’s teenage customers have been more motivated by environmental and cost considerations than other age groups, ThredUp spokeswoman Sam Blumenthal said. And investors have taken notice — according to Crunchbase, ThredUp has raised more than $380 million in funding.

“Definitely, we’re seeing a rise in conscious consumerism,” Blumenthal said. “A couple years ago, people just didn’t realize how bad their clothing was for the planet. People are starting to understand that fashion is one of the most polluting industries in the world.”

That realization is dawning for other kinds of consumer behavior too. Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg famously shunned airplane travel this summer, taking a zero-emissions sailboat to New York for the UN’s climate conference, and she is using an electric car rather than a petroleum-burning vehicle to drive around North America. (She made a stop at a rally in downtown Los Angeles on Friday.)

H&M Chief Executive Karl-Johan Persson dislikes movements that push back against consumerism. Last month, he told Bloomberg that choosing to decrease one’s environmental footprint by buying less or by refraining from carbon-emitting activities would have “terrible social consequences.”

“We must reduce the environmental impact,” Persson said. “At the same time we must also continue to create jobs, get better healthcare and all the things that come with economic growth.”

H&M isn’t backing away from the fast-fashion ethos of encouraging shoppers to buy the latest trends rather than focus on timeless and durable wardrobe staples. But it is trying to be kinder to the planet, with an initiative to use only recycled or sustainably sourced material by 2030.

The company says about 70% of a garment’s impact on the climate happens during manufacturing. By 2040, it plans to reduce or offset more greenhouse gas emissions than its entire production process emits — a goal it says it will reach in part by looking into new techniques that could absorb greenhouse gases. And since 2013, it has offered a clothing recycling program that lets shoppers turn in their unwanted clothing in exchange for a discount.

H&M also said it works with governments to help install solar panels and other renewable energy solutions to make factories more sustainable and has looked into using unconventional fabrics, such as textiles made from orange peel and pineapple leaves.

Fast-fashion pioneer Forever 21 Inc. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection this fall after being burdened by debt and falling out of favor with teens, but it’s nonetheless leaning toward environmental consciousness. The Los Angeles company said it’s trying out a textile- and shoe-recycling program in L.A.-area stores and is looking into using recycled products.

Those steps are helpful, but they don’t necessarily address the crux of the issue.

“As long as we look at clothes as disposable, we have a problem,” “Fashionopolis” author Thomas said. “And that’s where H&M is getting nervous.”

Some retailers, such as sportswear giant Adidas, are trying strategies that can have green side effects: They’re experimenting with personalized gear to cut down on returns, increase customer satisfaction and reduce inventory. The idea is that a customer who orders a shoe built to his or her specifications will be more likely to keep and use it.

Others taking steps toward eco-friendliness include Ralph Lauren, which announced a plan to use 100% sustainably sourced key materials by 2025, and designer Tracy Reese, whose collection for bohemian-inspired retail chain Anthropologie used non-harmful dyes.

“This industry is not going away,” said Elizabeth L. Cline, a journalist and author of “Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion.” “The question is, how do we make it sustainable?”

She favors a comprehensive, holistic approach that includes overhauls of manufacturing, distribution and materials.

“It’s not just one correction, it’s the whole,” Cline said. “Everything has got to change.”

Bloomberg was used in compiling this report.

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.