By Mary McNamara

Los Angeles Times

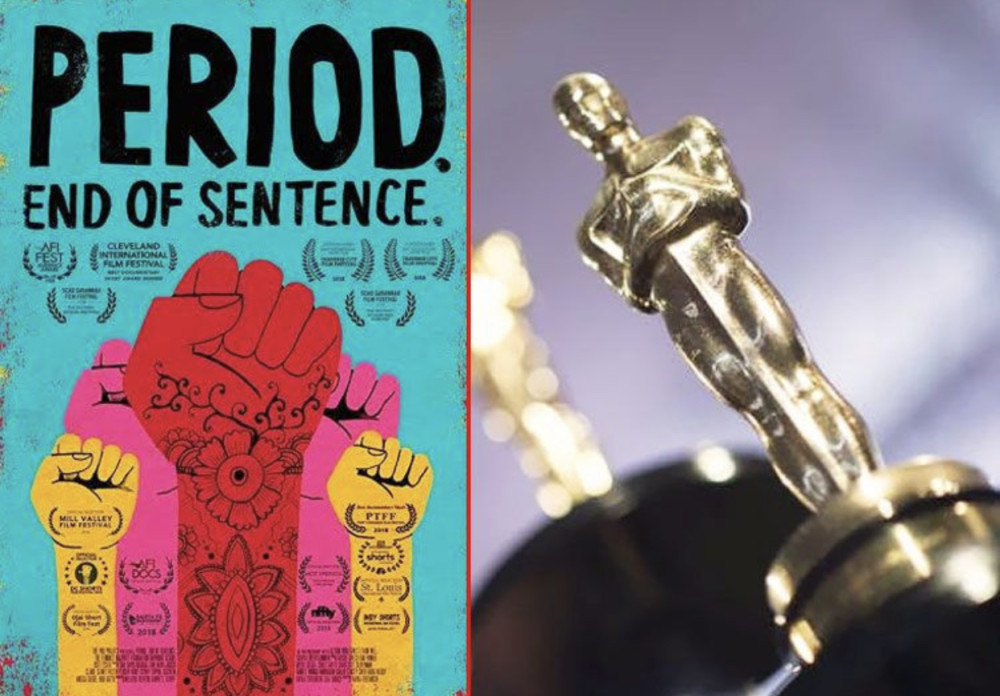

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) “Period. end of Sentence” is a documentary nominated for an Oscar. The film features the girls and women in a village in India where menstrual blood is considered dirty and shameful, a belief reinforced by the fact that most women there cannot afford, or do not know how to use, disposable pads.

Los Angeles Times

There are many reasons to be happy that “Period. End of Sentence.” is nominated for an Oscar.

The title alone is a breakthrough, the last time I saw a film with a menstruation marquee was in health class. And Rayka Zehtabchi’s short documentary examines the damage such cultural omission can do in a way that is quite specific and also completely universal.

The story of how a machine that makes sanitary pads came to a small village in India and changed the lives of the women living there is both a grim reminder of the basic obstacles millions of women still face in this world, only 12 percent in India have access to disposable sanitary products, and a hopeful message about how some of them can be solved.

In this case, a group of girls at a North Hollywood school raised funds to buy the machine and pay for the documentary to be made.

In the rural Hapur district, menstrual blood is considered dirty and shameful, a belief reinforced by the fact that most women there cannot afford, or do not know how to use, disposable pads.

As a result, many girls drop out of school once they begin menstruating, the cloths they use to protect their garments need constant changing, but there is often no privacy in which to change them, and the girls are too ashamed to ask for help.

Adult women often remain in their homes when they get their periods for the same reason, reinforcing the notion that menstruation requires isolation and makes women weaker than men.

A simple machine that allows local women to make pads, for their use and to sell, liberates them not only physically but also economically and emotionally in ways that make “Period. End of a Sentence.” the feel-good movie of the year.

It’s also, and correct me if I am wrong, the only Oscar-nominated film that even mentions the bodily function that occurs among more than half the adult population on a monthly basis. Even “The Favorite,” which revolves, quite intimately, around three women, side-steps the issue.

And it’s not just this group of films; Hollywood remains puritanically squeamish when it comes to menstruation.

Bloody violence, sex of all sorts, urination, defecation, ejaculation, evisceration, projectile vomiting and the messy reality of childbirth are all commonplace in modern film and television, but menstruation?

A female character is approximately 1,875 times more likely to be eaten alive by a zombie than to be seen coping with cramps or Shouting out a menstrual blood stain (seriously, why is this never used in ads for laundry detergent or stain remover?

It’s certainly a more common problem than grass stains. Who gets grass stains any more?

In cinematic stories involving more than one man, which is to say all of them, the urinal scene is apparently required by law, and erections are a common conversational thread. But how many times have you seen a female character step into the ladies room to change her tampon? Or canvas a crowd for Advil because she has the worst cramps in the universe?

I still remember the scene in “Terms of Endearment” when, being forced to put back grocery items they can’t afford, Debra Winger’s character’s son suggests they put back the Midol and she says, “No way.”

I remember it because it was funny but also because it was the first film I had seen make reference to the existence of menstrual cramps. (And there have not been many more since.)

There are exceptions, of course. We hear a lot about periods whenever they are missed, sending the plot into paroxysms of joy or despair.

Likewise, girl-gets-her-first is pretty standard on family shows, though apparently most girls get it only that one time; she then drifts into menses-free bliss like her mother and older sisters.

Unless, of course, the story needs to stoop to ye olde “embarrassed male relative must buy tampons” scene, which frankly should be stricken from the cultural lexicon.

Otherwise, menstruation remains such a narrative rarity that whenever it occurs, the “period pants” scene in “Broad City,” the “crime-scene tampon” riff in “Trainwreck,” the multiple uses of sanitary products in “Orange Is the New Black,” the stained bedspread in “Schitt’s Creek”, it is noticeable enough to be commented on, as either progressive or shocking. (The infamous “Period Sex Song” written for “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” was so shocking that it never made it on air, though it was released on YouTube.)

Watching “Alias Grace,” I was struck by a scene that showed the monthly towels in the laundry room, in all the kazillion costume dramas I watched as a critic and fan, I couldn’t remember ever seeing such a thing.

Excretory issues of all variety, yes, as well as injuries, illness and dental decay presented in bile-provoking detail, but unless it involved pregnancy/miscarriage, menstruation apparently was considered one gritty detail too many.

On “Downton Abbey,” hours were spent detailing cutlery placement, but what all those women did when they were bleeding each and every month remained a mystery; perhaps, they’ll clear that up in the movie.

American women may have better access to sanitary products than those living in Hapur, but the taboos presented in “Period. End of Sentence.” are not confined to India.

Plenty of American girls and women feel just as uncomfortable talking about their periods, and for similar reasons. (That women’s athletic uniforms still often include white or light blue shorts is proof of our shared obliviousness, why can’t the shorts just be black? Because female athletes don’t have enough obstacles to overcome?)

If men could menstruate, Gloria Steinem wrote 40 years ago in an essay with that title, they “would brag about how long and how much [and] sanitary supplies would be federally funded and free.”

Maybe. But in the world where women menstruate, it would be nice if, say, for every five scenes that take place at a urinal, there was one in which two women talked while dealing with their tampons. Because that happens all the time too.

The only other Oscar nominee that deals with intra-uterine activity is “Roma,” when Cleo’s (Yalitza Aparicio) water breaks rather spectacularly in a furniture store.

Screenwriters love spectacular water-breakage scenes, which are super-dramatic and medically absurd. But while most women live their whole lives without unleashing amniotic fluid in random inconvenient places, the vast majority do get periods. Every month or so, for years and years.

And maybe that’s worth mentioning, every once in a while.