By Diane Mastrull

The Philadelphia Inquirer

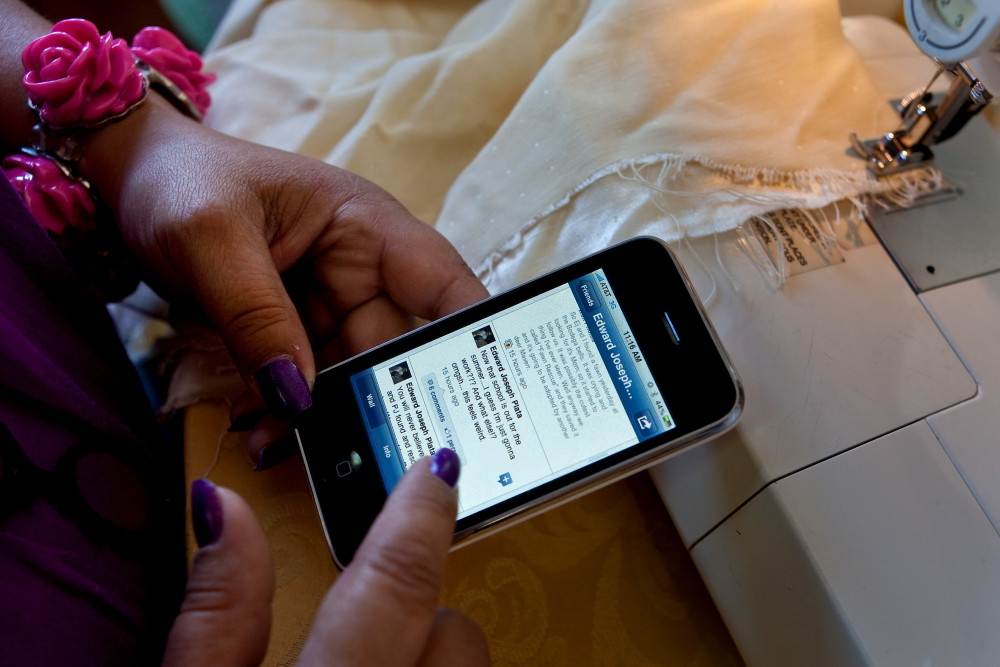

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) In this digitally abundant 21st century, when people just can’t seem to stay off social media, one longtime private investigator has put down the binoculars and picked up a laptop in the quest to find the truth.

PHILADELPHIA

Spying is pretty creepy. But cheating spouses and people who file false insurance claims have made poking around others’ business a necessary profession for a long time.

Which brings us to Scott Catron, a private investigator for more than 20 years.

His work has exposed him to dogs and wild animals during camouflage surveillance on public land. He has endured eight hours on a deep-sea fishing excursion to catch an insurance claimant evidently fit enough to work on the boat.

Then there were the six days he hid in a hatchback, waiting to capture visual evidence that a supposedly wheelchair-bound person could walk.

But time-consuming, shot-in-the-dark, rough-on-the-body tactics aren’t the only ways to learn all there is to know about a person, especially in the digitally abundant 21st century, when people just can’t seem to stay off social media, even when they’re attempting a scam.

Recognition of that truth inspired Catron and Michael Petrie, another longtime private investigator, to create Social Detection, where people searches involve fast, comprehensive internet scouring rather than days sitting in a car with binoculars.

“If there is fraud, it will be found, provided there’s a web presence,” said Petrie, 45, suggesting an important change in our personal record. “It’s not a reputation anymore. It’s a webutation.”

At Social Detection, which is moving from the suburbs to Philadelphia, the goal is not to hassle people but to stop insurance payouts to those not entitled to them, its founders said. By some estimates, insurance claims nationwide total $80 billion to $120 billion a year, with up to 10 percent fraudulent.

In less than six months, Social Detection saved insurance carriers and employers more than $7 million in eight cases, Petrie said.

Think a Google search is a comprehensive review of a person’s public profile? Watch Social Detection’s sleuths plug your essentials into Google and see the results. Then watch them do the same using their software and marvel, maybe cringe a little, at how much more comes up.

“There are a lot of sites that don’t let Google index their database,” said Catron, 44. “So you need to know what sites to go to.”

At Social Detection, “we’re going beyond the surface web,” using up to 50 identifiers, including nicknames, user names, email addresses, aliases, relatives, Facebook tags, texts, photos, and videos, ensuring more informed searches and, consequently, more relevant results, said David Graham, 52, another owner and director of business development.

All the information found is public. Social Detection never makes contact with individuals, the work is from a keyboard.

Following a rollout of a beta version of Social Detection’s proprietary software in April 2015 at the Risk and Insurance Management Society conference in New Orleans, business has been steadily building from its target market, insurance companies, third-party administrators, lawyers, and private-investigation agencies.

The 14-employee company, profitable and self-funded, would not disclose revenues, saying only that 2016’s will be about 2 1/2 times last year’s. About 20 percent is from subscriptions (mostly law firms and private investigators); the rest, from individual, or “concierge,” jobs.

Prices for concierge searches and reports range from $375 to $500. Subscriptions run $199 to $1,000 a month, depending on number of searches.

Jamie Kuebler is a New York litigation attorney who specializes in insurance defense work. He said he uses Social Detection “on every bodily-injury case. It’s really that good.”

The first time involved a claim by a man in his early 20s who had lost the tip of a finger in a work accident and was said to be suffering from complex regional pain syndrome (RSD) to the point where a bed sheet touching his hand caused unbearable suffering. The man also said he couldn’t raise his right hand. Even a physician retained as a defense expert believed him.

“I was looking at a case valued at $8 million to $10 million,” recalled Kuebler, who tried doing a search on Facebook, Instagram, and Google. But the man had a common name and while “a million things came up, I found nothing” on him, he said.

Social Detection found the man under an alias, turning up “hundreds of photos of him at amusement parks, him going down waterslides headfirst, going in pools, playing musical instruments,” he said.

The case settled “for peanuts,” Kuebler said.

Though Catron and Petrie started the business to serve the insurance industry, their focus as PIs for two decades, “we know it belongs in almost every category of business where people need to make critical decisions about people,” Petrie said.

Currently, access to Social Detection’s searches is not available to individuals, but it likely will be in the future for people to search themselves, connect with lost family and friends, even scope out online dating prospects, Petrie said.