Nara Schoenberg

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Statistical analysis found that one of the main factors accounting for the disparity was whether the patient was diagnosed at a Breast Imaging Center of Excellence (BICOE) accredited by the American College of Radiology.

CHICAGO

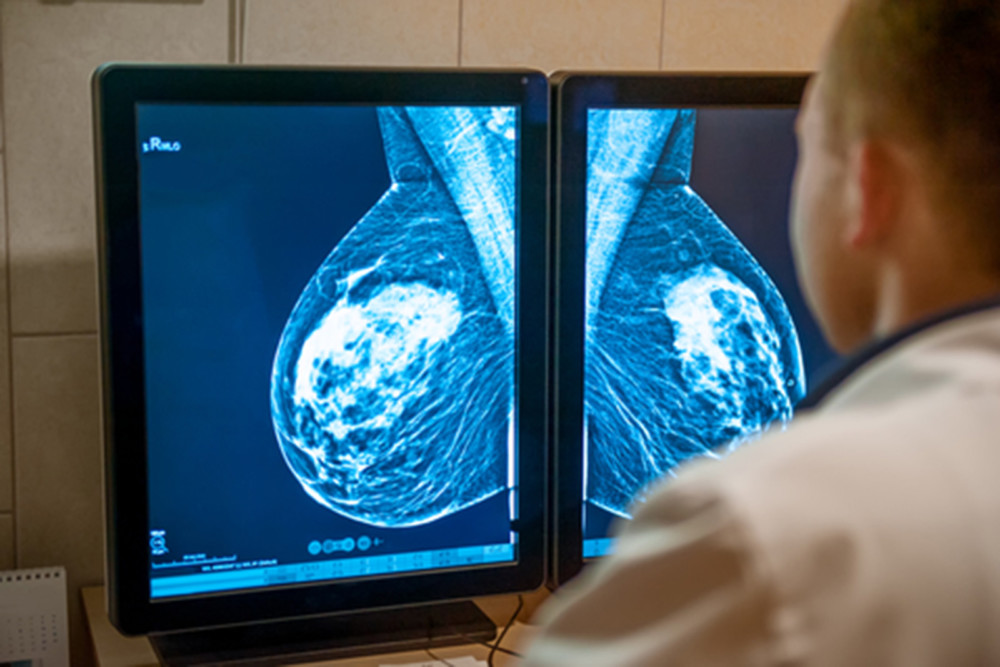

Black and Hispanic Chicago women are less likely than white women to get diagnosed with breast cancer early, when the illness is more treatable, in part because racial minorities are less likely to be diagnosed at high-performing centers of excellence in breast cancer care, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The study of 989 patients found that 35 percent of white patients were diagnosed at a relatively late stage, compared with 47 percent of black patients and 53 percent of Hispanic patients.

Statistical analysis found that one of the main factors accounting for the disparity was whether the patient was diagnosed at a Breast Imaging Center of Excellence (BICOE) accredited by the American College of Radiology.

While 81 percent of white patients were diagnosed at a BICOE facility, only 46 percent of black patients and 49 percent of Hispanic patients were.

“To have two health care systems in a city like Chicago is disgraceful,” said study co-author Richard Warnecke, a professor emeritus of public health at UIC. “I think the problem is that this kind of finding doesn’t get a lot of publicity, and it should. People are very cautious about how they criticize the medical system.”

The study, published online in the journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention in October, elaborates on a previous study by one of the authors but is more comprehensive and therefore more convincing, according to Bijou Hunt, an epidemiologist at the Sinai Urban Health Institute in Chicago.

“Data like this will hopefully move us toward a change where we will really see better care for everyone, not just for select portions of our population,” said Hunt, who was not involved in the UIC study.

Until about 1996, there was no racial disparity in breast cancer mortality, Warnecke said. But as methods of detection improved, white people benefited, resulting in a decline in the white breast cancer mortality rate, while other populations didn’t get access to improvements.

Today, blacks are 48 percent more likely to die of breast cancer than whites, both nationally and in Chicago, the study says.

The study gathered data from 2005 to 2008, with the aim of identifying policy changes that could decrease the minority mortality rate.

Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to be diagnosed at health facilities serving high-poverty populations. Only 11 percent of white patients were diagnosed at such facilities, compared with 37 percent of black patients and 47 percent of black patients.

The advantages of the better-resourced BICOE facilities include the on-site availability of an array of diagnostic tools, from screening to biopsy, Warnecke said. At a less comprehensive facility, a radiologist might not be available on a given day, or a patient might have to be referred to another site for an additional diagnostic test, causing a delay in final diagnosis.

“If a patient is appropriately referred (to a BICOE facility) and asymptomatic at the time of referral, then she has a good chance of getting an early diagnosis,” said Warnecke. “And this is particularly important for young women of color, who are much more likely to get the aggressive breast cancers than young white women.”

In addition to where a patient was diagnosed, the other major factor accounting for the disparity in time of diagnosis identified in the study was the mode of detection, or whether the problem was picked up relatively early by mammogram, as opposed to later by a patient noticing a lump or other irregularity.

One of the main takeaways from the study is that doctors should be more careful about where they send patients for breast cancer screening and diagnosis, Warnecke said.

He proposes changing the financial incentives for primary care doctors, who are currently reimbursed by insurers for each office visit in which they make a referral for screening or diagnosis.

Instead, Warnecke said, perhaps doctors should be paid for obtaining a final diagnostic result for the patient in a set amount of time, regardless of the number of referrals involved. That would encourage doctors to send patients to comprehensive, highly rated programs.

“This is something that could be done and should be tested,” Warnecke said. “What we’ve done is give people information that they can use to make beneficial changes.”