By Doug Livingston

Akron Beacon Journal.

AKRON, Ohio

Standardized tests show that girls, whether elementary students or college freshman, here or around the world, know more than boys.

In Ohio and elsewhere, girls score better in reading, writing, math and, to a lesser degree, social studies.

Boys do only marginally better in science, but as hard-wired gender roles shift and educators increasingly pitch engineering to underrepresented women, girls are catching up in that last subject where boys dominate.

Women are excelling in college, too.

Between 2009 and 2013 women, ages 24 and up, earned four-year degrees 64 percent faster than men. More shocking is that, also in that five-year window, the number of professional and graduate degree-holders grew 120 percent faster for women, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

Despite their academic achievement, women still earn less than men regardless of college. Though the wage gap is shrinking, the longer a woman spends in college, the more likely a man with the same education level will make even more than her.

Several theories attempt to explain why boys and girls have markedly different educational outcomes:

Because the academic gap exists across ages, societies and races, researchers suggest intellectual maturity and normal child development favor females. The gap is widest at the middle-school level.

Physiology plays a role. Adolescence can disrupt education as boys and girls develop. The age of puberty is when teachers begin to see the differences.

Behavior is big. Boys are 2 1/2 times more likely to be suspended and nearly three times more likely to be expelled, according to Ohio Department of Education data. They also drop out of school more often.

Girls might think differently. Educators say they are less oppositional and deeper thinkers.

Society could be to blame. Boys are encouraged to be aggressive, which would explain the defiant behavior and the dominance in high-paying corporate positions. Stereotypical gender roles drive boys to competitive sports and girls to reading and writing, two subjects in which they dominate boys.

The last reason is more nuanced. Is it possible that test results aren’t a reflection of academic potential, but instead suggest that the education system is failing boys?

Levels of heroines and princesses fill Jody Maxwell’s classroom at Helen Arnold Community Learning Center, a K-6 Akron Public Schools building.

Student desks are arranged in a circle. At the center, white violas bloom on a table.

The students face each other. Raising a hand and not their voices, they take orderly turns asking questions about a book they read.

As a learning tool, the book club tells teachers if students can lead productive, civil and thoughtful discussions.

But it’s the lack of boys that gives Maxwell’s girls the confidence and candor to speak up.

“There’s no distraction. It’s easier for us to focus,” said Treasure Brown, 12.

Last year, in mixed company, only two of the girls passed a reading test, Maxwell said.

“You spent all your time focusing on the boys instead of your class work,” said Nia Gary, 11.

This year, every girl passed. “They made huge gains in math, too,” Maxwell added.

In 2012 after nearly a decade teaching coed classes, Maxwell involuntarily transferred to Helen Arnold where she warily led the school’s first all-female sixth -grade class. “Since then, I’ve been advocating for it,” she said, now wary of returning to her coed teaching days. “If [the boys and girls] do anything together, it gets very chaotic.”

Segregating students is hotly debated and cyclical.

Grouping by academic performance, for example, was criticized in the 1990s for trapping minority and poor students while higher performing counterparts basked in each other’s broader life experiences, likely widening the gap.

In the 2000s, the practice was refined to a more controlled, small-group approach.

Critics of same-gender grouping say the practice produces an education that does not reflect the real world.

Proponents point to favorable evidence.

South Korea, for example, randomly assigns students to same-gender or coed schools. The practice is meant to avoid generational favoritism, a way to prevent family names from holding too much power. Regardless of its intentions, studies show boys and girls in single-gender schools have a better chance of joining the few who pass the country’s highly selective, government-run college entrance exam.

Separation of the sexes, especially in urban settings, does not directly address academics. Discipline often is the motivation.

Searching for ways to lessen the need to suspend or expel students, Schumacher Elementary split the sixth grade by gender this year. The grade level for this experiment, which has produced encouraging results, is key.

State data show the academic gap between girls and boys increases in sixth grade and doesn’t narrow again until high school _ and so do behavior problems.

“I don’t hear a peep from my girls or boys,” said Principal LaMonica Davis, who not long ago gave more suspensions to sixth graders than any other class at Helen Arnold.

No sixth grader attending Helen Arnold today has been suspended.

Balancing class sizes is the greatest barrier to sustaining or expanding the same-gender classes to other grades, which Davis and others would like to do.

Because enrollment by grade in a school can fluctuate widely, class-size challenges are amplified if divided by gender. Maxwell sometimes has fewer than 15 students or nearly 30.

A large single-gender class isn’t the worry, Maxwell argued. “It was easier for me to have 27 girls than a smaller class that was mixed because we stayed focused.”

Societal expectations

What society expects of men and women influences, to some degree, how teachers instruct and how boys or girls learn.

“I think our society is so confrontational for males. It’s such a hyper-aggressive society,” said Walter Jacoby, who coaches tennis to high school boys in Cuyahoga Falls and girls at Our Lady of the Elms, an all-girls private school in Akron.

Jacoby first taught inner-city boys and girls at Innes Middle School in the late 1990s. In the past 15 years teaching social studies to girls at the Elms, his thoughts about gender and education have evolved.

“Men get prized for their aggressiveness now, especially when I was in the inner city. It was bigger, stronger, faster. And the fact is that the only route out for so many of these kids is athletics. That’s what they’re pushed to.”

Then there’s the lack of stable homes in the city.

“There’s just not as many positive male role models. I taught at Akron Public Schools before I got here. No one had a father or father figure around, for the most part,” Jacoby said. “So there was tough modeling.”

Akron Public Schools is actively recruiting mentors to put strong male figures in front of boys at risk of slipping through the cracks.

Jennifer Milam, elementary principal at the Elms, approaches the issue as an academic. In her dissertation studying Early Childhood Education and Curriculum Studies in Texas, she observed a teacher call on only boys in a 45-minute lesson on dinosaurs, what might typically cover the walls in a little boy’s room.

“To some degree, it is so ingrained in us that girls are interested in this and boys are interested in this, that it is subconscious on the teacher,” she said.

But as the mother of a boy and a girl, the personal implications are ominous.

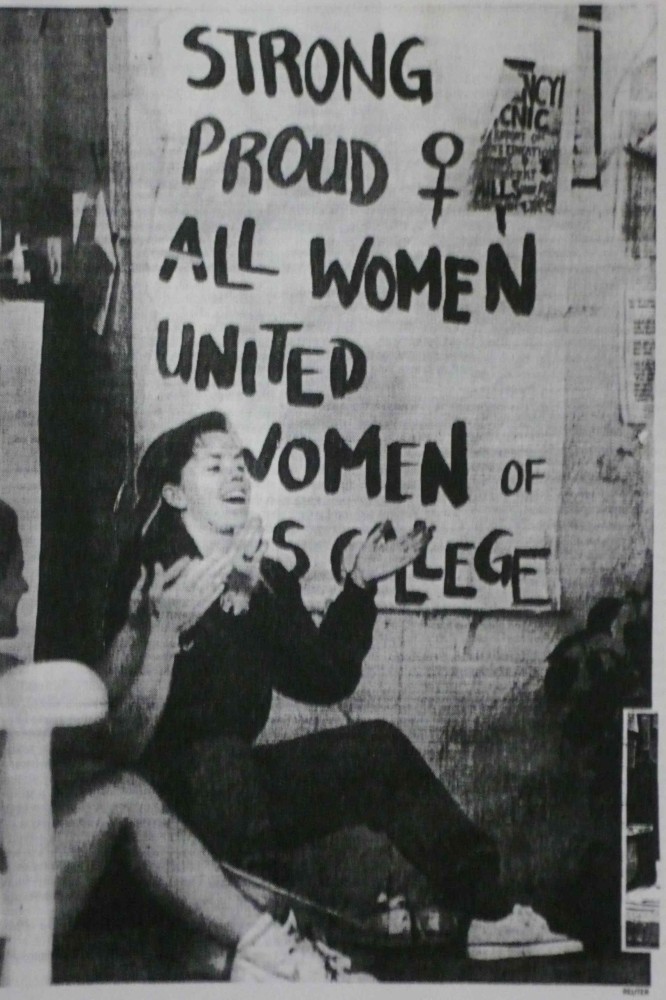

“If my son decides he wants to be a ballet dancer, he’s going to catch a much different response from the people around him. And he’s only in first grade,” she said. “In our world today, I think it is much more acceptable for young women to be confident and strong than it is for men to be kind and nurturing. We still have that same old stereotypical vantage point.”