By Phoebe Wall Howard

Detroit Free Press

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Phoebe Wall Howard takes us through the timeline of how a team quickly came together at Ford to create faceshields for first responders dealing with personal protective equipment shortages.

DETROIT

Sometimes miracles happen because every little thing goes right. And people involved are smart and creative and fearless.

This is the story of a hairstylist, a team of automotive prototype designers and a massive global company that in just a few days went from creating high-tech cars guided by artificial intelligence with the use of robots to old-fashioned built-by-hand assembly the way things were done back in the 1900s.

It sounds like a Hollywood movie script.

It was, in fact, real life in Detroit in the time of the novel coronavirus.

Ford Motor Co. executives issued a call to action March 19, after receiving an alert from the Mayo Clinic. Ford immediately assembled a task force to address the personal protective equipment shortage.

Within hours, the automaker decided to pivot from building cars to manufacturing medical devices, setting into motion the first steps that would generate tens of thousands of protective face shields for doctors, nurses and first responders during the rapidly spreading pandemic that causes respiratory crisis.

Within one week, a small team of designers from a shop within the company called D-Ford would collaborate virtually to review plans, design prototypes, build the early designs, meet with doctors, test prototypes, redesign, re-test and redesign.

Detroit helps NYPD

By last Thursday, the team would deliver thousands of face shields to Henry Ford Hospital, Beaumont, Detroit Receiving, and the first responders who did so much to save lives after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the New York Police Department and New York Fire Department .

The plan would go so well that the 25,000 face shields built would become 40,000, with a goal of 1 million a week. All by hand.

But let’s back up a minute.

The brains behind this feat work at a lesser-known entity within Ford, a “human-centered” design shop called D-Ford, with offices in London, Shanghai and Palo Alto, California.

Events unfolded faster than anyone could imagine. Here’s how it all happened:

On March 19, the design team was given the cue to explore what can be made to help and quickly. Teams scoured the internet for open-source designs to build from that required few materials and supplies they could easily source from Ford’s existing network.

“We were activated and really got going on Friday (March 20),” said Will Brick of Berkley, a prototype design lead at D-Ford, who is based in Dearborn. “We were all working remotely, and through the weekend, early mornings to pretty late at night. The mornings will start with a round of phone calls and meetings.”

They got word from people advising Ford that face shields were top among the items of personal protection equipment that hospitals would need , so they latched onto disposable face shields for hospital workers.

“They have a plastic protector, it’s like a thicker version of a report cover that kids would use when they handed in a school term paper, an elastic band around the head that mitigates against aerosols and splatter from getting into the eyes, mouth. Like a plastic shield. They’re often wearing other protective equipment under that,” Brick explained. “So we rounded up our team. We had phone calls, web chats and we started to brainstorm.”

Emergency huddles

The team needed to understand the problem from the customer’s perspective, he said.

“We agreed to quickly do two things: Reach out to area hospitals directly and try to establish contact with people living with this shortage of material in that moment,” Brick said. “We wanted to look around and see what we could find out there in the world that might already exist or might have thought of _ what’s already out there that we could leverage and put into production quickly, even if it was just temporary.”

His wife, Erin, is a hairstylist. And two of her clients happened to be emergency room doctors at the Detroit Medical Center and Henry Ford Hospital System. She reached out to them. And that started the thread.

“They introduced us to key folks,” Will Brick said. “During the day on that Friday (March 20), we talked about prototypes with Sinai Grace, Henry Ford and Detroit Receiving. We worked with the hospitals to get firsthand feedback.”

While all this was happening, designer Dave Singh was looking at open-source designs produced at the University of Wisconsin and talking with Professor Lennon Rodgers, director of the Grainger Engineering Design Innovation Lab, about what had worked and not worked with hospitals.

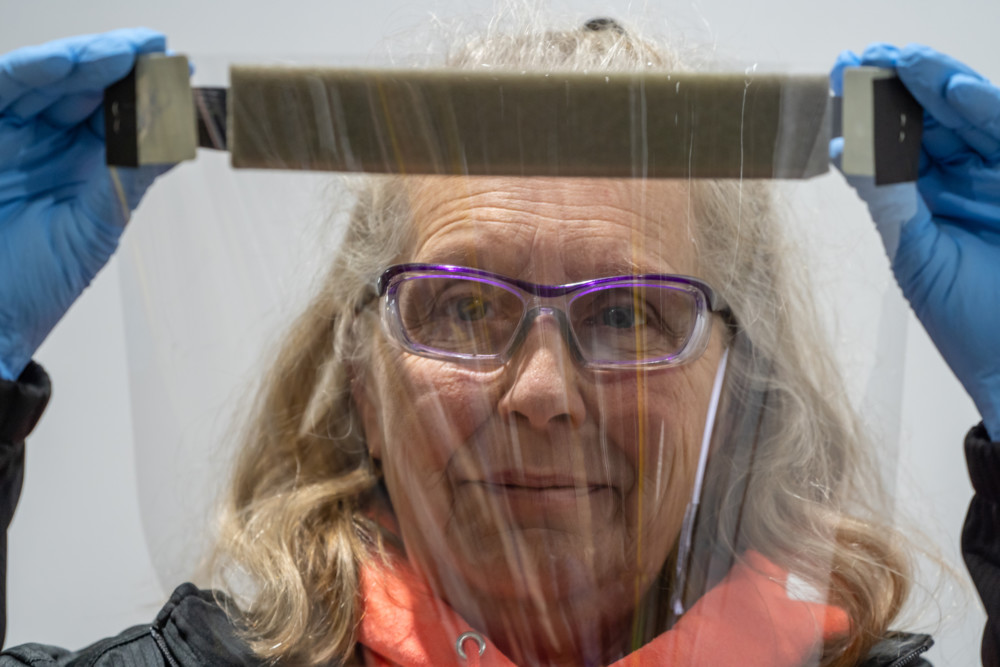

“We needed materials that were simple, available in relatively large quantities,” Brick said. “The design uses a thin transparent flexible plastic sheet widely available in roll form and found from Ford suppliers in giant rolls. Then there’s a strip that goes across the forehead to hold the shield away from your face, like a 1-inch-by-1 1/2 inch strip of foam glued to the plastic shield, and an elastic band stapled to either top corner of the shield.”

Brick and his colleague Jeff Sturges found a space near Eastern Market in downtown Detroit to work so they could be close to the doctors for review and discussion and testing, specifically Henry Ford Hospital and the DMC.

“We actually sat down with folks with physical prototypes in hand, to have them try them on. It was a big win that we were able to confirm that we had something that would work for them.”

Within 24 hours of the go-signal, the prototype team was building in earnest by March 20, he said. “We had contacts by the end of that day, started meeting them on Saturday and making physical prototypes by hand. We had Howard Lew from Ford picking up materials from Ford suppliers and driving to where we were working at Eastern Market and meeting hospital folks. By Sunday, we had three prototypes made to give to doctors and then adjustments needed and we figured out how to manufacture these.”

Like Grey’s Anatomy

“We got feedback right away,” Brick said, and received FDA approval.

By last Tuesday, he said, they had dropped their first shipment of 1,250 face shields to metro Detroit hospitals.

“This is a privilege,” he said. “I never thought I’d be taking a box of face shields produced at Ford and deliver them to the hospital and see instantly in that moment the good that was done. It’s Ford and we’ve got more than 100 years of industrial experience and capability and know-how.”

Within seven days D-Ford made it all happen. The design company took a few very simple pieces of material and built a face shield like the kind surgeons wear on popular TV shows like “ER” or “Scrubs” or “Grey’s Anatomy.”

Now Will Brick, who woke up in the night, pencil by his side, continues to jot down ideas before they fade.

“A lot of people are part of this moment,” he said. “I have two very small children and we’re all in the middle of this together.”

Front-line work

Meanwhile, workers like Pat Tucker, 55, of Roseville, Mich., wake up at 3 a.m. to get ready for work and drive to Troy for a 6 a.m. start making the face shields.

“We made almost 30,000 today,” she said Thursday. “The first couple of days, it was a little rough until we got the hang of it. We have tables set up, and the area is marked off with red tape so we’re all 6 feet apart. We wear the masks we’re making while we work, and gloves. They’re lightweight and not hot.”

Assembling three pieces to make the device is tedious but crucial. It all involves a plastic shield, a sponge and a strap. That’s pretty much it. Peeling off the adhesive to stick the sponge to the shield and staple the strap. They’ll work 10-hour shifts and take a half-hour lunch.

“I’ve worked in prototype assembly for nine years. Now this,” said the UAW member. “I care a lot about my country and the people in it. I can’t believe this is happening. I don’t understand why it’s happening.”

Tucker said, “We’re doing a simple thing to save a life. We’ll run two shifts, a night shift and a day shift. It takes less than 10 seconds to make one. The longest process is peeling off a stickie. We’re trying to do 100,000 a week.”

Helping heroes

Todd Jaranowski, 57, of Milford is president of Troy Design and Manufacturing in Plymouth, a subsidiary of Ford with offices in Chicago and China, too. He oversees the teams building the face shields. He said UAW members are essential to the process. They’re working voluntary hours now.

“We started out with 40 people and we’ve grown to 80,” he said. “We really kicked off our first prototype on Monday (March 24). We had 25,000 on Thursday,” he said. “We’ll steadily ramp up. We had to quickly design an assembly process.”

It’s sort of primitive, the way it’s described. Just putting little pieces together and passing it along.

“The UAW has been unbelievable,” Jaranowski said. “Our goal is to make a million a week. Generally, there’s no automation. We had to keep in mind social distancing and set up a production line so people are safe and 6 to 7 feet away from one another.”

What’s powerful? Getting photos back from doctors and first responders, he said.

“Those people, they’re the heroes,” Jaranowski said. “We’re just trying to keep them safe.”

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.