By Carolyn Said

San Francisco Chronicle

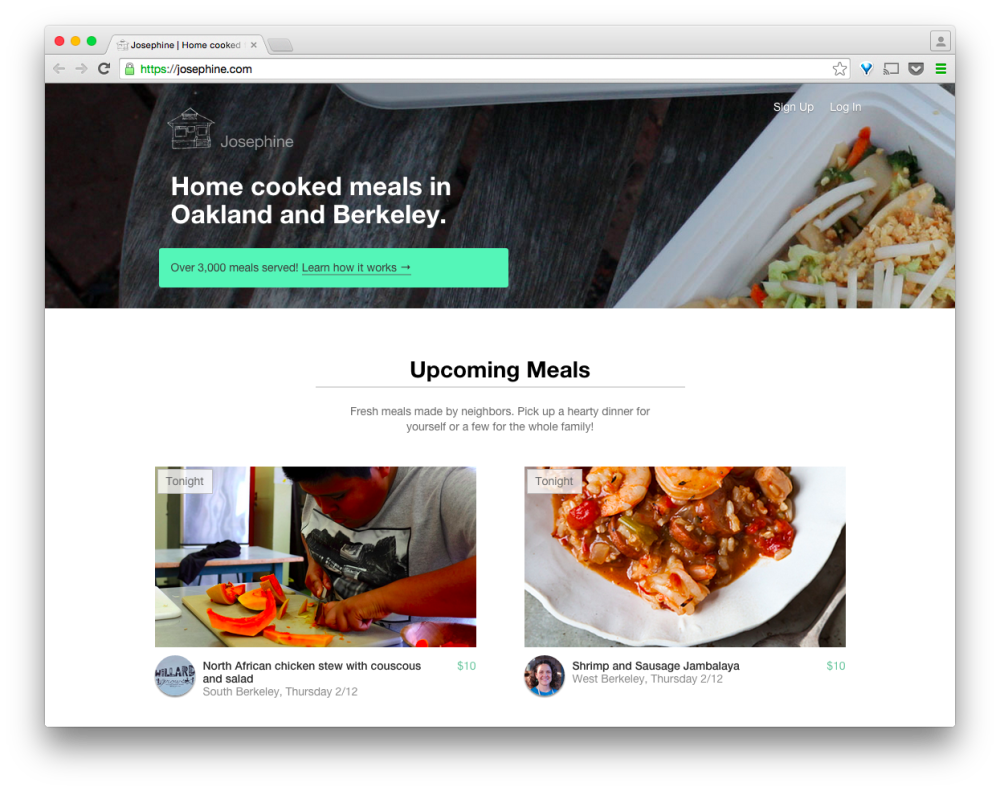

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) An online marketplace called “Josephine” that helps small-scale entrepreneurs sell home-cooked meals is picking up “steam.” However, regulations regarding food safety could make things “sticky” for these new home-based chefs. The website seems to be especially empowering for women in business who want to stay at home with the kids and run a business.

San Francisco Chronicle

Renée McGhee loves to cook and to talk about food. She weaves tantalizing descriptions of her recipes, every element whipped up from scratch. “My favorite main dish is what I call my Maui Pork Bowl: grilled pineapple, pickled peppers, pulled pork in a sweet, smoky, spicy sauce that I make with layers and layers of flavor,” she said.

McGhee, 60, has turned that passion into a part-time gig thanks to Josephine, a marketplace that lets home cooks sell meals to nearby customers who pay around $12 per serving online and then come to pick up the food.

Last week she moved deliberately around the tidy kitchen in her Berkeley apartment, ladling the pork dish atop rice in take-out containers, as about a dozen people came through to pick up meals, some of them so eager they started chowing down right there.

“Josephine gives me an opportunity to do what I love, and pay bills while doing it,” she said. “I’ve met so many wonderful people.”

But although her kitchen is immaculate, McGhee — and Josephine — occupies a legal gray zone. California, like most states, bans sales of food cooked in a personal kitchen. A 2013 law, the California Homemade Food Act, also called the cottage food act, does allow home cooks who meet certain criteria to sell items that don’t need refrigeration, such as bread, pies, candy, granola, mustard and nut butters. That change inspired a wave of entrepreneurs.

Now Josephine is mounting an effort to reform state law to let small-scale entrepreneurs sell home-cooked food in person at their homes. It would legalize Josephine’s model, as well as those of underground restaurants like EatWith and Feastly that offer paid dinner parties in people’s homes.

“We’re trying to create a space where people who love to cook can succeed,” said Josephine CEO Charley Wang, who co-founded the company in late 2014 with Matt Jorgensen, naming it after a friend’s mother who nurtured them when they moved to the West Coast. “Our legislative system has been outpaced by technology and our social evolution.”

Josephine will host a series of town halls for cooks, consumers, regulators, health-safety advocates and others to discuss the issue, starting with an event Wednesday at its Oakland co-working space. Assemblywoman Cheryl Brown, D-San Bernardino, is on board to sponsor a bill next year after all the interested parties have had a say.

“There need to be some pragmatic regulations to allow folks to cook healthy food safely and share it easily,” said Babak Bafandeh, co-founder of Cuchine, another home-cooks marketplace that operates in San Francisco. “Food cooked with love resonates with people much more than industrial food.”

But the issues are complex.

Justin Mallon, who represents some 1,600 California county and town health inspectors as executive director of the California Conference of Directors of Environmental Health, said his trade group is open to seeking a way to legalize the sale of home-cooked food. But food safety is the first concern. In his view, any law would need equipment requirements, such as refrigerators that can maintain a temperature; food handling rules, including training for cooks; and some limits on the number of meals or people served.

“The local regulators aren’t insensitive,” he said. “We want to find a balance between a free-for-all and maintaining a level of public service and public trust.”

In-person inspections of the kitchens are a basic prerequisite, he said. California law requires restaurants and other enterprises to pay the cost of annual inspections, which can range from a couple of hundred dollars to several thousand a year for big-box stores with bakers and butchers.

Both Josephine and Cuchine, which are very small, counting their cooks in the dozens, said they already do their own inspections of home kitchens and require all cooks to get California food handler certificates. Both say they’d be delighted to have government inspectors take over.

And beyond the food concerns, issues about zoning, parking and noise could easily arise — as they have for Airbnb’s vacation rentals — if marketplaces flourish and home cooks see a steady stream of take-out customers at their door.

Airbnb, Uber and Lyft followed a classic Silicon Valley playbook of pursuing widespread growth that often defied local laws, and then seeking legislative changes to accommodate their models. Josephine says it’s trying to do things differently.

“There are two approaches to innovation outpacing regulation,” Jorgensen said. “Innovators can work around the system or within the system through policy change. For most tech companies, evading the regulatory system for as long as possible has been the default. We see an opportunity to engage in the political process and bring stakeholders into the conversation.”

As policy director at Oakland’s Sustainable Economies Law Center, Christina Oatfield helped create the Cottage Food Law.

“We love the concept of supporting people accessing healthy, local, homemade meals,” Oatfield said. “But this legislation needs a lot more thought and work.” Besides food-safety issues, she thinks any law should protect the cooks from financial exploitation.

Josephine’s founders already frame it as creating flexible work to help people make ends meet, the same argument put forth by Airbnb, Uber and Lyft.

“What makes Josephine special is that people can do it at home,” said Ben Jealous, a partner at Kapor Capital, which invested in Josephine’s seed round, seeing it as fitting his firm’s mission of supporting social enterprises (Josephine has about $2.5 million in backing). “You can watch your kids and have a home-based business. These are entrepreneurs finding a way to empower working families financially and to make more nutritious food available to the rest of us.”