By Brittany Meiling

The San Diego Union-Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Handmade clothing is experiencing a surge in popularity. Some suggest the interest in sewing may be spurred, in part, by recent and widespread criticism of fast fashion.

The San Diego Union-Tribune

Fabric stores that sell threads, buttons and materials for making clothes are dwindling in San Diego, with owners shuttering their shops citing waning interest from customers.

The disappearance of fabric stores is probably not a shock to outsiders, in the age of fast fashion, who still makes their own clothes? But sewing garments at home is, surprisingly, not dead.

While fabric stores of yesteryear are falling off the map, a new industry is rising up to meet the modern demands of young “sewists”, a relatively new term that describes anyone who sews. And these businesses look quite different than your grandma’s fabric shop.

But you wouldn’t know of sewing’s resurgence by looking at San Diego’s retail scene. Last month, news broke that family-owned Yardage Town would close its four remaining stores in San Diego County, leaving the region with a dearth of stores selling apparel-grade fabrics. Besides a smattering of chain hobby stores whose selection of apparel-worthy fashion fabrics is slim at best, there are few remaining brick-and-mortar shops to buy fabric for making clothes.

Before Yardage Town announced its upcoming closures, a slew of predecessors had already closed down. Jane’s Fabrique, a fashion fabric shop in La Jolla, shuttered 10 years ago. National City-based Yardage City, not to be confused with Yardage Town, closed its stores a few years later.

“When we lose Yardage Town, the choices here will be next to nothing,” said Gwen Edwards, a longtime dressmaker and owner of Gwen Couture in South Park.

In a city of 1.4 million people, why is it so hard to find one good fabric store?

The new “sewist” emerges

Sewing clothes was once considered a basic, practical skill, but it began to fall out of fashion with the baby boomer generation. Mothers were working and had less time for such tasks, and the price of clothing was plummeting. By the time boomers had their own children, their memories of such skills were faint and increasingly unnecessary.

With home economics disappearing from classrooms, millennial-aged Americans (and younger) never learned the skill at all.

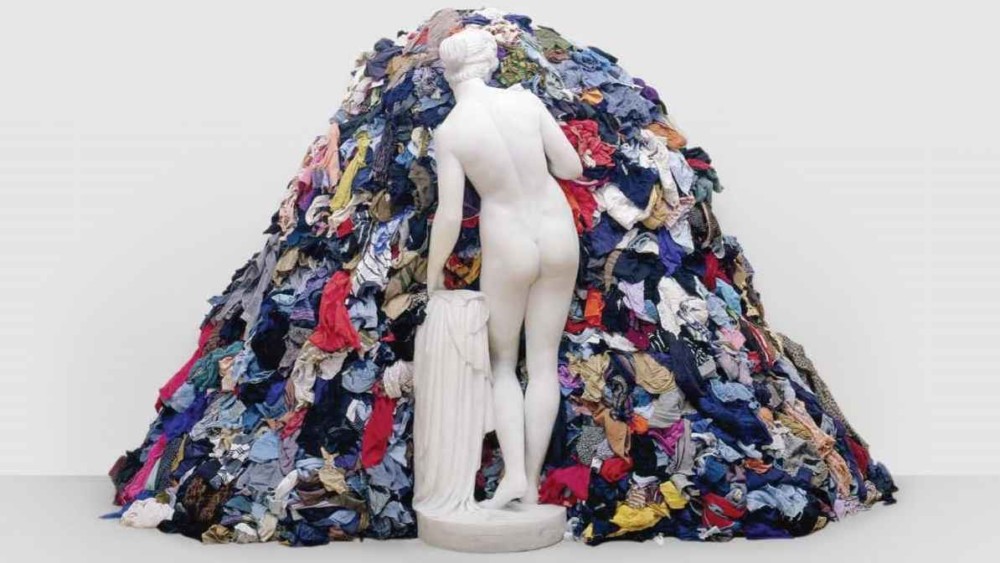

But in the past 10 years, sewing clothing is experiencing a surge of popularity among these generations. The sudden interest is spurred, in part, by recent and widespread criticism of fast fashion.

Awareness of the fashion industry’s uglier side dawned in 2013, when a garment factory in Bangladesh collapsed, killing over 1,100 people. Since then, documentaries such as The True Cost sparked nationwide concern over ethics in the fashion industry. More recently, popular comedian Hasan Minhaj aired an episode titled “The Ugly Truth of Fast Fashion” on his hit Netflix series, “Patriot Act,” in November, shedding light on the environmental concerns tied to fast fashion.

“There’s a huge interest in slow fashion,” said Sarai Mitnick, owner of Collete Patterns and Seamwork Magazine in Portland. “People are asking more questions about where their clothes come from.”

These new sewists are coalescing on social media, learning new skills through videos, taking part in online sewing challenges on Instagram, and creating podcasts to share tips with one another.

“We believe the increase in social media and online learning has massively accelerated the renewed interest in sewing,” wrote Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos, hosts of popular sewing podcast Love to Sew, in an email to the Union-Tribune.

The podcasters were shocked by their own quick success. Since the Love to Sew podcast launched in August 2017, the show has accumulated over 2.7 million downloads, with a current rate of 30,000 downloads per week.

“We had no idea the podcast would be such a big hit with the community,” the hosts wrote. “It immediately took off and is now the No. 1 garment sewing podcast out there.

The spike in the public’s interest in sewing is reflected in Google’s search trends, where the phrase “sewing classes near me” has steadily climbed over the past five years.

Modernizing an old-fashioned industry

The online community has stirred a steady stream of millennial-friendly sewing businesses, who are joining the $36 billion craft and hobby industry.

Sewing patterns, the paper blueprints home sewers use to create clothing, have changed dramatically in the past decade. Once dominated by brands birthed in the 1800s such as Vogue and McCalls, the sewing pattern business has ballooned to include countless online-only startups, such as Friday Pattern Company and Grainline Studio.

These newcomers are often led by young women who are drafting modern, easy-to-understand patterns that can be downloaded and printed at home.

Mitnick, a former Google and YouTube staffer in Silicon Valley, founded her pattern startup Collete Media nine years ago. The company was unique at the time for offering inclusive sizing, downloadable patterns and modern technology to reach customers. The company links all of its patterns with hashtags on Instagram, allowing shoppers to share pictures of their completed projects.

“A lot of people were interested in sewing, but not a lot of companies were serving them 10 years ago,” Mitnick said. “Since then, tons of other small businesses have popped up and gained quite a following.”

Closet Case Patterns is one such example. The Montreal-based startup has capitalized on the generations who were never taught to sew at home. The company churns out beautifully produced videos with professional instructors who teach viewers how to make garments step by step.

Intimidated by tailoring? You can buy their series on how to sew a classic blazer for $59, pattern included.

These new startups saw what the industry’s relics didn’t: younger generations needed different tools than their grandparents did. More help, less tissue paper, and a community to share their progress with.

The problem of fabric

While this community of sewists bubbles to life online, they’re experiencing a unique problem. There’s nowhere in town to buy fabric.

From rural communities to high-fashion cities with garment districts, independent fabric stores are dropping like flies.

If aspiring sewists want to peruse fabric in-person, they are often limited to chains like Joann Fabrics or Walmart, which stock loads of colorful prints, seasonal holiday fabrics, and material better suited to quilting than apparel.

Some beginner or hobby sewists in San Diego will hunt for fabrics at the National City Swap Meet, where sellers unload swaths of discount, stretchy knits and colorful prints for as little as $1 a yard. Edwards, the dressmaker in South Park who also teaches sewing classes, said her students sometimes even resort to scouring thrift stores for garments they can deconstruct.

“Once you get past making pajama pants, it’s really hard to find good fabric,” said Mardel Backes, a retired middle-school teacher in Poway. “There’s almost nothing in San Diego.”

The lack of fabric stores is likely driven by two trends: the slow erosion of brick-and-mortar retail, and the changing preferences of home sewists.

Many people aren’t sewing to save money, and that’s new

Backes, for example, didn’t grow up sewing, but taught herself the skill in adulthood. Today, she likes making high-quality clothing with fabric that will stand up to time and wear. This winter, she made a fashionably oversized camel hair coat, lined with warm sienna silk. She regularly makes trips to Los Angeles, where she spends hours perusing shops for things like rich-feeling silk charmeuse, lace or boiled wool.

Backes most prized creation is an embroidered silk dress designed with a chiffon yoke.

“The fabric was so beautiful,” Backes said. “I had no idea what I was going to do with it when I bought it, but I had to buy it. “

Such inspiration is not easily available in San Diego. The fabric stock at chains like Joann, she says, are often cheesy and cheap-looking.

“The reason we sew clothing for ourselves is to make a quality project you can’t get in stores,” Backes said.

This sentiment is shared among many new sewists, said Bernadette Banner, a fashion YouTuber who specializes in making historic costumes and “historically inspired” modern clothing. Banner saw a huge spike in her online following over the past two years after she made a series of viral videos criticizing the lack of quality in fast fashion.

In 2018, Banner only had 1,000 subscribers. Little more than a year later, she’s amassed over 550,000 subscribers. Her video comparing her handmade clothes to a fast fashion knock-off has been viewed over 3.3 million times.

“I think people are inspired by the craftsmanship, quality and thought that used to go into clothing back in the day,” Banner said. “Especially now, when we are saturated with overconsumption. There’s something charming in seeing something that has taken time to be crafted beautifully. It’s novel nowadays.”

In the comments on Banner’s videos, her fans marvel over the detail, sturdiness and quality of her hand-stitched clothing. Turned inside out, Banner’s clothing is just as beautiful on the inside as it is on the exterior.

Hand-felled seams hide all raw edges, and acute attention to detail leaves no thread out of place.

But creative craftsmanship isn’t necessarily why older generations would sew their clothes at home. Before the days of fast fashion and cheap, synthetic materials, it was expensive to buy clothes. It wasn’t that long ago when sewing was the most economical choice, and price was the priority of home sewers.

“My mother-in-law had nine children, and she would sew all their clothes because it was the most cost-effective way to do it,” Backes said.

Today, home sewists often spend far more money constructing a custom dress at home than they would spend buying an off-the-rack item at Forever 21. Backes forked over $100 for the quality fabrics she used to create her camel hair coat. Granted, it was probably less than she’d spend on a new designer coat, but it also wasn’t a thrifty project.

An opportunity in the fabric industry

Stores like Yardage Town, Joann, or Walmart, with their discount fabrics and affordable synthetics, are behind. They aren’t targeting a generation that values craft and quality.

This is why Backes and her small group of sewing classmates travel up to Los Angeles to buy their materials from Mood Fabrics. Founded in 1991 in the New York City fashion district, Mood specializes in designer brands and premium fashion fabrics. It also has a massive online presence, which shores up its brick-and-mortar spots in Los Angeles and New York. (Yes, it’s the same Mood Fabrics from Bravo’s TV series Project Runway).

Like all retail these days, fabric stores likely can’t survive without an online presence. Giants like Amazon-owned Fabric.com dominate the Internet scene, but independent sellers are getting into the game, too. And with fabric stores dying off, the Internet is where most young sewers are buying their material.

According to Banner, that’s a travesty.

“One of the most common questions I get is where to shop online for fabric,” Banner said. “But online is not the way to go for fabric shopping. There’s no way to see how fabric behaves, you need to touch it; see how it moves. If you’re a beginner, you’ll learn a lot slower by shopping online.”

Edwards, who gets commissions to make dresses for clients, said it takes the spontaneity out of sewing.

“As a dressmaker, I can’t do anything on a short timeline anymore,” Edwards said. “I have to order swatches online first, and then the whole process is weeks added to the time of making the garment.”

For Backes, she thinks the death of old-fashioned fabric stores, and the surge in creative sewing, creates an opening in the market for a new player to be successful.

“Maybe within five years or so a high-quality fabric store will open in San Diego,” Backes said. “I think it would do quite well. Sewing used to be a dying art. But it’s not dying anymore.”

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.