By Tamara Dietrich

Daily Press (Newport News, Va.)

If British Nobel laureate Tim Hunt had “trouble with girls” before, it’s nothing to the trouble he’s having now.

Two days after the 72-year-old biochemist told a roomful of scientists and science journalists how “disruptive” women scientists are in a lab, even suggesting separate labs for women, the backlash forced him to resign his honorary professorship at University College London.

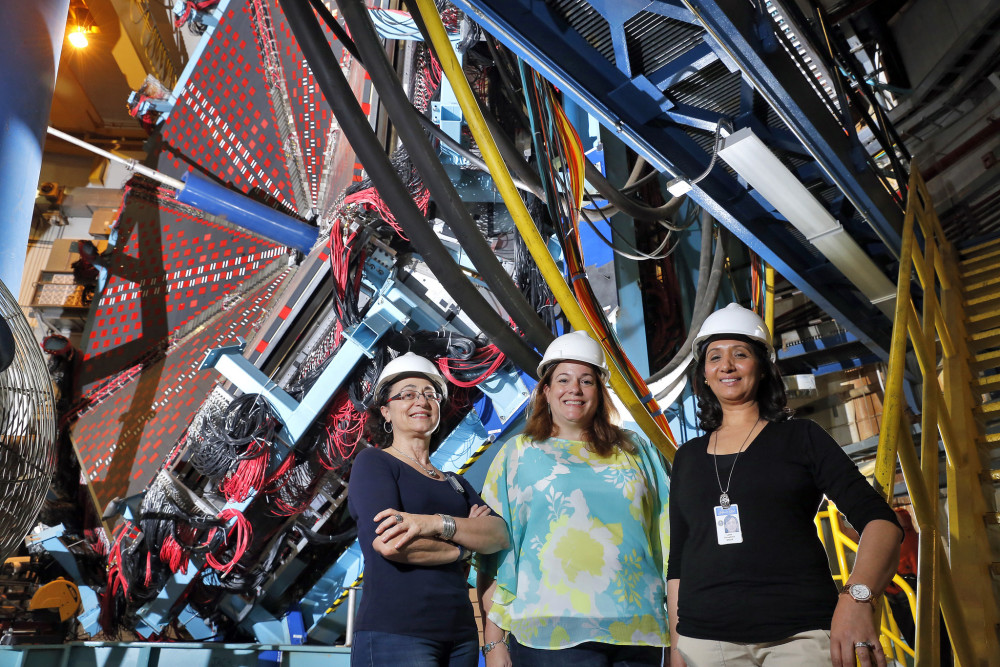

“It created quite a fire,” said physicist Fulvia Pilat, deputy associate director for accelerators at Jefferson Lab in Newport News. Jefferson Lab operates under the U.S. Department of Energy to conduct particle physics.

The firestorm centers around Hunt’s remarks on June 9 at the World Conference of Science Journalists held in South Korea.

“Let me tell you about my trouble with girls,” Hunt said. “Three things happen when they are in the lab: You fall in love with them, they fall in love with you, and when you criticize them, they cry.”

Hunt has since issued an apology for causing offense, explaining he was being “light-hearted” yet also “honest.”

“I did mean the part about having trouble with girls,” Hunt said in news reports. “I have fallen in love with people in the lab and people in the lab have fallen in love with me and it’s very disruptive to the science because it’s terribly important that in the lab people are on a level playing field.”

For Pilat, the uproar is both timely and ironic. Last month, she led a panel discussion on women in science — particularly why there are so few of them in developed countries like the U.S. and Great Britain — at the International Particle Accelerator Conference in Richmond. Jefferson Lab hosted the conference this year.

Hunt’s remarks, she said, are evidence “there’s still work to be done.”

Generational bias

Other women working in the sciences in Hampton Roads say the remarks are both unsettling and inaccurate.

“I do work in a lab and, no, it has never been an issue,” said Kristin Wustholz, assistant chemistry professor at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg. “I find the more diverse the lab is, the more creative the science.”

Her colleague, associate psychology professor Jennifer Stevens, said when she heard the remarks she immediately considered the source.

“We’re more likely to see that kind of comment coming from a scientist who is of that age,” Stevens said. “I don’t want to call him old, but I do think that there is this generational bias.”

And the risk there, she said, is that the bias could get passed down.

“Those are the people who are mentoring upcoming faculty,” Stevens said. “So there’s sort of this downstream effect.”

Hunt’s comments also raise some interesting questions, she said.

“You can turn the tables on him quite easily and say that the problem with having old white males leading labs is that they’re always hitting on younger females,” Stevens said. “That’s the problem, because they’re in the power position.

“You can turn the tables on that similarly and ask the researcher, ‘What are you saying to the female? Maybe you’re more critical of them and they’re more likely to cry.’ The other thing is, men are less likely to cry in public, but it doesn’t mean that you’re not insulting them just as much. It doesn’t mean you’re not damaging their personal self-worth.”

Stevens participates in the Women in Science Education (WISE) program at William and Mary designed to advance women in the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

It’s one of a number of initiatives at universities, national laboratories and elsewhere to increase the percentage of women in science careers.

‘Thanks, Mr. Hunt’

Like Pilat, Patrizia Rossi has worked in physics for decades and pushed to boost the number of female physicists in Anglo-Saxon countries. In their native Italy and in many Latin American countries, the percentage of women physicists is far higher.

So if there’s an upside to the comments, said Rossi, deputy associate director for physics at Jefferson Lab, it’s the swift reaction to condemn them.

“I would say, ‘Thanks, Mr. Hunt,’ because it really helps the cause,” Rossi said.

Besides, she said, if love should spark in a laboratory, it’s no different than any other workplace.

“It’s human nature that we fall in love — men and women fall in love with each other,” Rossi said. “It’s good, it’s wonderful. It’s just as important you have to be able to deal with this kind of situation and learn how to deal, and to separate the professional part to the personal part.”

The women say they’re seeing positive changes among younger men and women entering the sciences.

“They’re brought up with just completely different attitudes,” Pilat said.

Young female scientists even took to social media to respond to Hunt, including a Twitter campaign to post photos of themselves in their laboratories under #distractinglysexy.

One scientist posted a photo of herself suited up in a formless, full-body white jumpsuit with gloves, cap and face mask as revealing as a burka, with this caption:

“Idk [shorthand for ‘I don’t know’] how any men were able to function when I was in this bunny suit and integrating a satellite.”

B. Danette Allen, a senior scientist at NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, posted a photo in a similar get-up with this caption: “Stopped sobbing for this photo in shuttle Discovery bay.”

Yet another scientist posted warning labels from her lab. Next to one listing the classic “danger symbols” was the warning “mixed gender laboratory space.” And near the “no smoking, eating or drinking” sign was “no falling in love, no crying.”

Pilat said the Internet can play an important role in changing attitudes.

“Scientific change is really interesting — it goes fast,” Pilat said. “Technological change, it goes in a heartbeat, and there’s no problem in having one technological improvement after the other. But changes that are rooted into education, society and ethics and so on and so forth, these are the things that usually take a long time.”