By Nina Metz

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Melissa Silverstein, founder and publisher of the news site Women and Hollywood says, “I think we need to be really careful in how we handle these stories.”

Chicago Tribune

It is inevitable that the #MeToo movement will be turned into TV and film. But whose stories are being told? And who gets to tell them?

The answers feel, well, actually kind of predictable for Hollywood.

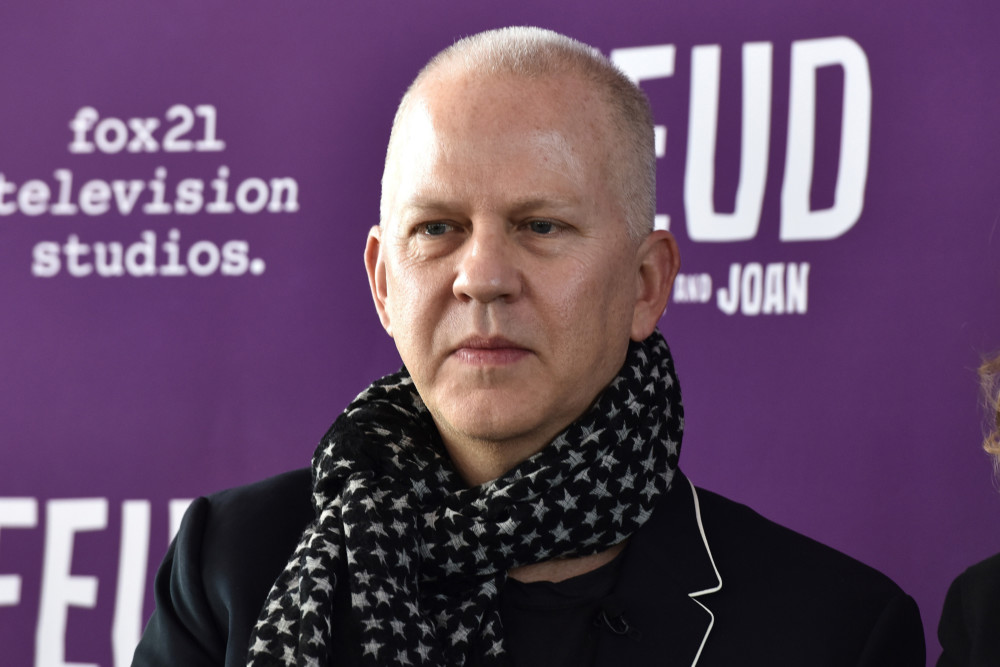

Last week, the New Yorker published a long and fascinating profile of TV producer Ryan Murphy and in it, he mentioned an idea for an anthology series called “Consent.”

Each episode would tackle a different storyline, “starting with an insider-y account of the Weinstein Company.

There would be an episode about Kevin Spacey, one about an ambiguous he-said-she-said encounter.”

Murphy’s shows, from “Glee” to “American Horror Story”, are tonally varied, but share what he describes as a “maximalist” approach to storytelling.

There is a grandness and an over-the-topness to his style and I’m not sure that aesthetic is suited to the (still) highly contentious topic of sexual violence and workplace harassment. Especially when he-said/she-said is such a common defense tactic used by harassers themselves; why in the world would Murphy consider lumping that in with anything exploring #MeToo?

Another high-profile project is Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” described as a collage of stories about a group of people looking to make it in Hollywood during the summer of 1969, set against the backdrop of the real-life murders of Sharon Tate and friends, which were set in motion by Charles Manson.

“I think we need to be really careful in how we handle these stories,” says Melissa Silverstein, founder and publisher of the news site Women and Hollywood. “One of the great conversations we have been having is: Who are the storytellers? And whose stories are centered in our culture? … We must ask these hard questions. Why are these projects being made? Why are they being funded? Why are these stories more valid than others?”

Let’s go through some of the odd connections with the Tarantino film: At the time of Tate’s murder, she was married to film director Roman Polanski, who nearly a decade later would be arrested on a number of charges concerning the drugging and rape of a 13-year-old girl. He pled to a lesser charge before fleeing the country.

Earlier this year, audio from a 2003 Tarantino interview with Howard Stern resurfaced, in which the director defends Polanksi, insisting: “It’s not rape for these 13-year-old party girls.”

Tarantino has since apologized: “I realize how wrong I was,” he said, adding that he “incorrectly played devil’s advocate in the debate for the sake of being provocative.” This was on the heels of Uma Thurman’s account of her time working on the “Kill Bill” movies, and the dangers involved with a choking scene Tarantino insisted on performing himself, and a driving stunt that left lasting damage.

And then there’s this: “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” is scheduled to be released next summer on the anniversary of the murders. Tate’s sister Debra Tate told the pop culture website Vulture she is outraged: “How is this not vulgar? Or sick? THIS IS NOT A CELEBRATION.”

Both Tarantino and Murphy wield enormous clout in Hollywood. And they share a love for exploitation, for shock and bigness and provocations, especially when it comes to violence; these are identifiable traits that we see in their work again and again, and it’s fair to ask, what are the risks when these types of stories are filtered through the prism of Murphy’s or Tarantino’s style?

Last summer culture writer Lindsey Romain wrote a piece with the headline “Tarantino is the Right Man for Manson” offering a different point of view: “For all the brutality his films display, they have never felt to me, a person who flinches at guns and has no love for most action films, gratuitous or unkind. … And more to the point, I love Tarantino’s women.”

I asked her if she still felt the same. “I wrote it before the Weinstein stuff broke, before the Uma Thurman piece broke, so I probably would not have written that piece in this climate,” she said.

“But my opinion hasn’t totally changed because the plot sounds like it’s more about Hollywood and how it was shifting in 1969, which is a revolutionary period in America in general.

The Manson murders were kind of the tail end of that and people consider that date the end of hippie culture and the love movement of the ’60s. True crime has a tendency to focus on the bad men at the center of it, so just knowing that Sharon Tate’s story was going to be told in some tangential way, that drew me in.”

And, she added: “We don’t know yet the level of exploitation that will actually exist in the film.”

But it’s constructive to listen to what Murphy and Tarantino are saying. They’re telling us how they view the world and approach their work.

Of his widely-lauded “American Crime Story: The People v. OJ Simpson,” Murphy told the New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum that “I have a hubris problem.” And on his instincts for a hit show: “There’s something for everybody, and there’s something to offend everybody. That’s what a hit is.”

As for Tarantino, he says his upcoming film is “probably the closest to ‘Pulp Fiction’ that I’ve ever done.”

Notably “Pulp Fiction” includes a rape scene involving a sex slave known only as The Gimp. Rolling Stone published a piece a few years back analyzing the scene and it cites Tarantino originally wanting to use the song “My Sharona” because it had a “really good sodomy beat to it. I thought, oh, God, this is just too funny not to use.”

The casualness with which Tarantino talks about these kinds of things is striking, and it’s worth asking why he’s mostly been able to brush off criticisms of the last few months.

Erin Shannon, who is pursuing her Ph.D. at the University of York in England, is studying institutional responses to sexual violence. “Pop culture influences how we understand issues,” she told me.

“And when it comes to sexual violence, that pop culture framing is often already sensationalist. When you add in the over-the-top styles of Murphy or Tarantino on subject matter that is already so exaggerated in media, you are running a very high risk that no meaningful conversation is going to result.”

A hyper-stylized approach, she said, “rarely has room to consider nuances and exhibit sensitivity, both of which are necessary in any discussion of sexual violence. We will see people talk about these shows and movies because of the content matter, but when it comes to sexual violence, it is how it is depicted that matters, not that it merely is.”

All of this is theoretical. Not one frame of Tarantino’s film has been shot yet. Murphy’s idea for “Consent” is just that, an idea. It may never come to pass. And to his credit, he has been proactive about dismantling Hollywood’s old boys network on his own shows by launching his Half initiative, which ensures equal opportunities for women and minorities behind the camera.

Romain, whose work has appeared in Vulture, Thrillist and Teen Vogue, told me that his idea for “Consent” reminded her of “when the ‘Game of Thrones’ guys were going to make ‘Confederate’ for HBO and it was announced at the height of Black Lives Matter. It’s just this weird thing where these cis white men get it in their head that these are their stories to tell somehow.

“It’s so fresh,” she said, “I don’t get this desire to immediately be like, ‘Let’s make a show about this really gross thing happening.’ If you want to examine it after there’s been some real change and we have a little more to go on, OK. But this feels like trying to capitalize on something that’s not even healed yet. We’re still right in the middle of it.”

I know I’d be more interested in a fictionalized show, about anything, really, in which one of storylines focused on a characters we’re invested in experiencing sexual harassment. What does that look and feel like? And what are the costs when a victim decides to push back? That type of approach would likely feel more organic, more creatively meaningful, than Murphy’s ripped-from-the-headlines proposal.

Let’s say he pushes forward with “Consent” and hires all women as writers and directors. And we’ve yet to hear any reports of female-created projects about this subject matter, particularly from women of color, who we in the media too often erase from the #MeToo discussion.

Expect a certain amount of squeamishness from studio and network execs who might be uncomfortable with any pitch that aims for realism, it might hit too close to home.

But a bit of soul searching wouldn’t hurt. “Especially when it relates to violence,” said Women and Film’s Silverstein. “We are fed up of women’s bodies being used as a canvas for telling stories.”