By Angela Carella

The Stamford Advocate, Conn.

Lucy Loglisci’s story would not be remarkable if it had not happened when it did.

She ran a successful restaurant in downtown Stamford, but she did it in the 1950s, when few women worked outside the home, let alone became entrepreneurs.

It wasn’t her only obstacle. Lucy was an Italian immigrant who had never written a check and, as she would say, couldn’t count change without using her fingers.

Yet her business brought her family out of poverty, and her restaurant became a hangout for celebrities of the day.

Now her grandson, Anthony Cortese, owner of Silver Pin Studios in Stamford, has made a documentary about her life.

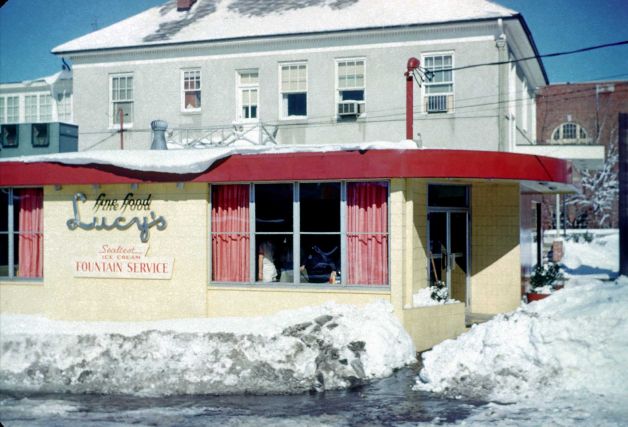

Cortese hopes it will interest people who remember the Starlite Drive-In Theatre once on Shippan Avenue, where Lucy’s homemade Sicilian-style pizza stole the show during intermission, or Lucy’s Diner on Prospect Street, which expanded to become JR’s Cocktail Lounge.

Cortese hopes the documentary also will attract people interested in a bit of Stamford’s story, or in the story of a welcoming woman who knew how to work hard and take life head-on.

Cortese’s documentary will premiere Sept. 4 at the Italian Center on Newfield Avenue, with most of the proceeds going to research of Alzheimer’s, the disease that claimed Lucy’s life in 2010.

“She was a big part of Stamford during her snapshot in time,” Cortese said. “It was when Stamford was putting itself on the map.”

Lucy was 39 when she began to put herself on the map. It was 1951, and Lucy and her husband, Louie Loglisci, were living in a six-family house with their four children, renting an apartment that was not nearly large enough.

Her neighborhood in pre-urban renewal Stamford was becoming unsafe. Lucy decided she had to do something to bring in more money.

A relative told her about a part-time job at the Starlite Drive-In, which then was across the street from Cummings Park.

At first, Lucy was embarrassed about the nighttime job. In those days, women stayed at home with their children.

And she knew nothing about the operation of a theater concession stand, where she was assigned to run the popcorn machine. For a while, she just hid behind it, her children explain in the documentary.

But she quickly overcame her fears.

“She told one of the partners in the drive-in, Bill Sobel, that the frozen pizza they were serving was horrible, and she asked him if she could make it at home instead. He said yes,” Cortese said. “Pretty soon, it was their best-seller.”

Sobel installed a pizza oven for Lucy, and one day gave her a surprise. It was an ad running on the big screen during intermission. It featured a drawing of Lucy and invited moviegoers to try her delicious pizza.

“That was a big deal for an Italian immigrant housewife,” Cortese said.

A few years later, Sobel decided to sell his portion of the drive-in. He told Lucy he was buying a coffee and sandwich shop on Prospect Street and asked her to be his partner.

Lucy didn’t know anything about business partnerships. So she spoke to her eldest son, Ralph, who had just returned from service in the Air Force and needed a job. Ralph Loglisci put up the money the Air Force paid him when he was discharged.

They opened Lucy’s Diner in 1955.

They had a lot to learn, Cortese said. At first no one got paid. Lucy cooked and waitressed. Ralph ran the grill. In the documentary, Ralph jokes that the hours were 6 a.m. to 3 a.m., no days off.

But people came for Lucy’s pizza. She began to make her macaroni and meatballs, her lasagna, her frittata. More people came.

It was an innovation, Cortese said.

“People were used to eating hamburgers and hot dogs at places like that. Then it was a special thing to go out for Italian food,” he said. “Lucy was making it commonplace.”

When her other son, John Loglisci, came out of the service, he joined the business. The diner had only a counter, but soon the family added a dining room.

“In the daytime they got a lot of business from Stamford High School, which was just up the street, and from the courthouse down the street,” Cortese said. “At night they would get a lot of business when the bars closed, and they had a lot of customers coming from meetings and events at the Italian Center, which at the time wasn’t far away. Ralph used to say it would get so busy that he would be standing at the grill in eggshells up to his ankles.”

Lucy’s Diner grew with Stamford. Its customers were the construction workers putting up the office buildings all around it, and then the office workers in those buildings.

Lucy rode the wave of trends — drive-in movie theaters to diners to cocktail lounges. That last one was the era of the “businessman’s lunch,” Cortese said.

It got going in Stamford in the late 1960s.

“A lot of corporations were coming into Stamford, and there was not a lot of nightlife downtown,” he said. “My grandmother and my uncles wanted to capitalize on the business clientele that was emerging. They were evolving with Stamford.”

So in 1970 they closed Lucy’s Diner for a few months for renovation, then reopened it as JR’s Cocktail Lounge, named for her sons John and Ralph. There was jazz music, a piano bar, a dining room for lunch and a supper club, with Lucy’s cooking.

“There weren’t a lot of places like that then, and even fewer that served homemade Italian food,” Cortese said.

It thrived. It caught on with celebrities who came to the Stamford area to live or work. New York Yankees legend Joe DiMaggio ate there often, and usually ordered pasta e fagioli, which Lucy would make especially for him.

Actor Henry Fonda would go with his wife, who was trying to get him to eat healthy. But Fonda liked spaghetti aglio e olio, which he would order in a whisper.

Miss America pageant host Bert Parks ate there so often that he and Lucy became friends. During her 50th wedding anniversary celebration, Parks sang, “There She Is, Miss America,” as Lucy walked in.

Other celebrity restaurant guests included Frank Sinatra, singer Jerry Vale, comedian Phyllis Diller, film director Cornel Wilde, and actor Lorne Greene, star of the TV hit “Bonanza.”

In the documentary, Lucy’s family members talk about her attitude toward her customers.

“You could live in a cardboard box or you could be a multimillionaire. It didn’t matter,” one said. “When you walked in the door, you were her friend.”

The characters who came into the cocktail lounge captured the teenage Cortese’s imagination.

“It was dark in there. When you went in, it took your eyes a few minutes to adjust,” said Cortese, now 48. “It was kind of like that commercial, ‘What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas.’ I’m pretty sure a lot went on in there. When I was there, I always felt like I was in a movie.”

Originally a web designer, Cortese began the Lucy documentary about three years ago, shortly after launching Silver Pin Studios.

“My grandmother had a great run. I always wanted to tell her story,” he said. “She was so independent. It was hard for her to lose that to Alzheimer’s the last 10 years of her life. I hope this will raise some money for Alzheimer’s research.”

Once JR’s closed in 1988, Lucy returned to being a housewife, caring for her husband until he died in 1992.

After her success, Lucy was given an award by the youth service group Boys’ Town of Italy. In her acceptance speech, Lucy said,

“In my business, I met people from all walks of life, all different views and attitudes,” but it meant little.

“We are still all one,” Lucy said. “We must learn to put aside differences, to change to a positive attitude, to forgive those people we think have done wrong. Don’t allow bitterness to form a barrier that will prevent you from having a full life. This is what life is all about.”