By Gillian Graham

Portland Press Herald, Maine

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) 93 year old Norma Ham Merrill was one of at least 10,000 American women who worked behind the scenes of the war, breaking complex codes used by the Axis Powers and providing critical intelligence to the United States Army and Navy.

SCARBOROUGH

It was 1942 and the United States was still reeling from Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. In desperate need of workers, the Army and Navy scoured college campuses and small towns for women willing to do top-secret work to help win the war.

Norma Ham Merrill, an 18-year-old office worker in Massachusetts newly inspired by a visit to her workplace by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, answered the call.

“When you saw what needed to be done, you did it. That was the motto then,” she said. “I felt I could join the Navy and do some good.”

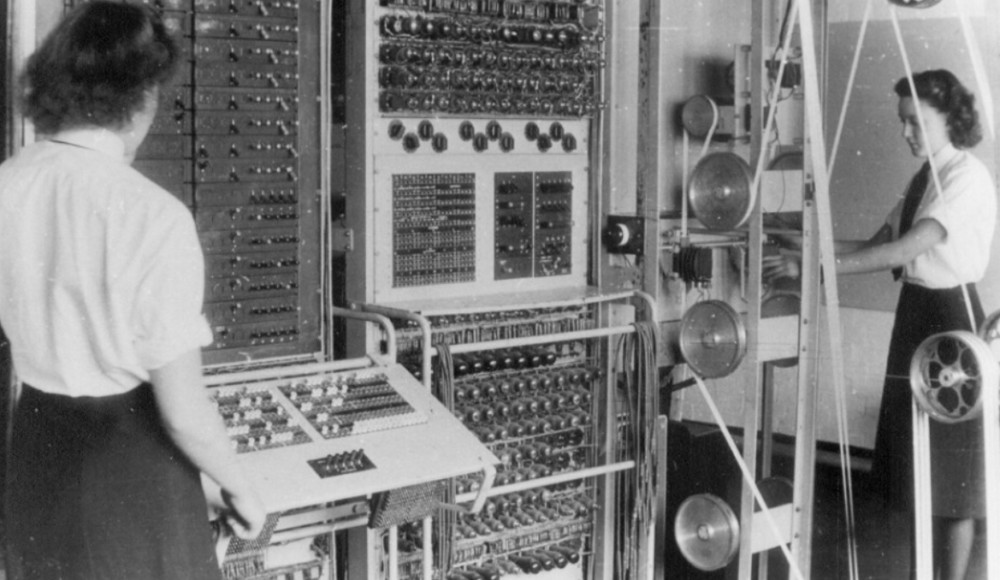

Merrill was one of at least 10,000 American women who worked behind the scenes of the war, breaking complex codes used by the Axis Powers and providing critical intelligence to the United States Army and Navy. The women were told constantly that “loose lips sink ships” and ordered to never reveal the scope of their work.

Norma Merrill, 93, says memories of the messages she coded and decoded have faded with time, but she recalls tidbits. For example, “when we surrounded the enemy, the code was ditty-dum-ditty,” she said.

So the women, Merrill included, kept quiet.

It wasn’t until a generation later that the women were recognized for their wartime service and given benefits like those extended to other veterans. In the years after the war — when Merrill was busy raising two children and working as a registered nurse in Portland — she didn’t talk much about the top-secret work she did in Washington D.C.

Memories of the messages she coded and decoded have faded with time, but Merrill still recalls tidbits about the work she did day in and day out.

At 93, her fingers now sit curled toward her palms, a physical reminder of the years spent handling reams of the inch-wide tape that held enemy messages.

“When we surrounded the enemy, the code was ditty-dum-ditty,” she said recently during a visit at the Maine Veterans’ Home in Scarborough, where she has lived for the past few years.

Merrill was born on Christmas Day, 1924, in New Hampshire, one of three daughters of a veteran of World War I. The family moved around and the girls’ formal schooling was at times interrupted, but Merrill’s mother taught her daughters at home. During high school, Merrill would work after classes in the office of the superintendent of schools, then for a few hours each evening as a restaurant cashier.

That superintendent later vouched for Merrill, allowing her to get the security clearance she needed for her work in the Navy.

Merrill said she had not given much thought to joining the military until Roosevelt made a stop in Worcester, Mass. where she was working in the purchasing department of a local company. She watched as the president, paralyzed by polio, emerged from a train with a son on either side holding him up.

“You wouldn’t have known he was paralyzed if you hadn’t already known,” Merrill said. “I decided then I would join.”

Merrill was sent to Washington D.C., where she lived in Navy barracks on the banks of the Potomac River, near the cherry trees she still describes with fondness.

Merrill and the other code breakers worked long hours and, at the end of their shifts, were driven back to their barracks in special buses so they wouldn’t be kidnapped and forced to give up sensitive information. But the tight security meant they were largely confined to their barracks during off hours. They passed the time sunbathing on the roof, much to the delight of young pilots who flew low over the building on training flights to catch a glimpse of the ladies.

After the war, Merrill returned to New England and applied for a job as a receptionist at a hospital where a supervisor encouraged her to use the G.I. Bill to go to school.

Inspired by her own childhood battle with polio, Merrill headed to Maine General Hospital School of Nursing and became a registered nurse.

She married twice, had two children and tended to patients in a 20-bed ward. Later, she worked at the Maine Youth Center caring for children she felt no one else was looking out for.

After she retired, Merrill moved to Florida and became the chaplain of the Tampa WAVES group. She gave inoculations to migrant children and dedicated countless hours to raising money for the Washington D.C. memorial for servicewomen and to support fellow veterans, many of whom were homeless.

“So many of them, their families deserted them. I felt they needed all the help they could get,” she said.

Merrill was living at an armed forces home in Gulfport, Mississippi, in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit, filling the building with water up to her thighs. She was among 400 veterans who were evacuated on 10 buses to Washington D.C. carrying only what they could hold in their arms. She soon returned to Maine to be near her daughter and live at the Maine Veterans Home in Scarborough.

In October, Merrill took an Honor Flight to Washington, where she was recognized for her service, serenaded by the Six-String Soldiers and posed for photos at monuments. She had seen the Women’s Military Service Memorial once when it was dedicated, but that visit was a blur of banquets and speeches and big crowds.

This time, in the city with the cherry trees she loves, she had time to pause and reflect.

buy diflucan generic buy diflucan online no prescription