By Maggie Gordon

Houston Chronicle

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Professional organizer Marie Kondo promises in her books and in her TV series, that if you follow her method, you’ll never rebound to a life of clutter.

Houston Chronicle

Erica Smith is crouched on the floor of her West University Place home, staring into a plastic bin of more than 100 Easter eggs.

“Look at this,” she says as she rakes her fingers through her collection, accumulated over 11 years as a mom.

Small eggs and large ones. Polka-dotted, striped and solid. Pastel, glittery and neon. It’s too much, Smith realizes, as she examines the stockpile in detail for the first time.

“Oh, my gosh,” she says as a defeated laugh bubbles from her lips. “How does this happen?”

Her task right now is one familiar to many in the Houston area, as the KonMari organizing craze returns to the public consciousness this winter, thanks to a new and utterly binge-able Netflix series starring spritelike organizer Marie Kondo.

Smith needs to sit with each of her possessions, hold them and ask herself, “Does this spark joy?” before deciding whether to hang on to her things or discard them.

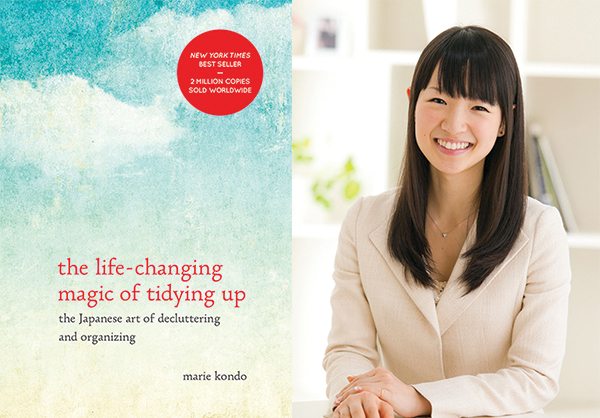

The KonMari method is nothing new. Kondo was already a household name with a six-month waiting list for her services in her native Japan when her book, “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up,” became a best-seller in America in 2014. This prompted a new cottage industry of certified KonMari consultants, who undergo hours of training to earn their positions.

Ashley Barber, who sits at Smith’s right during the Easter-egg mission, is one of six certified KonMari consultants in Texas. And as the only one in Houston, she’s seeing plenty of business these days.

“Traffic has definitely picked up in terms of the number of emails I get for consultations and inquiries. Definitely lots more,” Barber says as she stands in Smith’s tidy white kitchen. “I was pretty busy before this, but it’s definitely got a lot more interest since Netflix.”

Though the original fanfare for KonMari rolled out among the barre and yoga set, many of whom first read about Kondo in the New York Times and high-brow magazines, and can afford Barber’s $375 fee for a tidying session, this second wave, borne of Netflix, has a much more Everyman (OK, make that mostly Everywoman) feel.

Want proof? Check your neighbor’s trash piles on pickup day. Or head to a local thrift shop and size up the influx of clothes on the racks. As Houstonians clean out their own closets, all that stuff has to go somewhere.

Last week, the heaps of clothing dropped off at the Cottage Shop in Montrose reached such heights that the thrift store had to announce a rare move: It suspended donations for what shop manager Cheri Burleson says is just the second time in her long tenure at the store benefiting The Women’s Home.

“Definitely this month has been a massive amount of donations. And it’s not just maybe one or two bags. People are coming in with truckfuls,” Burleson says.

And it’s not a coincidence.

“I kept hearing donors saying when they’re donating that they’re watching this new series on Netflix,” she says.

January has long been known as a perfect time for such a phenomenon, as Americans add life goals to their personal lists in an effort to finally make an honest phrase out of “New year, new me!” But the Kondo craze that’s been sweeping through Houston’s dresser drawers, folding everyone’s clothes so they stand upright, sells itself as something more permanently life-changing than other fads such as Whole 30, P90X or whatever new better-living mantra your cousin is hashtagging on her Instagram feed this week.

Kondo promises again and again, both in her books and in the series, that if you follow her method, you’ll never rebound to a life of clutter.

“It’s hard to believe that there’s no rebound,” Smith says, standing in her kitchen with Barber. “I think the big fear for me is I’m going to do all this, and then I’m going to revert back. So when I finally read the book, and she said, ‘My clients don’t rebound.’ I was like, ‘OK, I’m going to trust that.'”

But it felt like a leap of faith — one that Smith first took last spring, and has been gently working through since, in what has now stretched to an eight-month process.

“So far in my experience, no one has rebounded either,” Barber tells her. “If you finish. If you finish. And that’s the caveat. If you truly go through the whole thing and get through it all, you won’t go back.”

This promise is part of what makes the KonMari method so appealing to people who casually tuned in to the show when it was released on New Year’s Day.

Well, that and science.

“The feeling of control and autonomy, and confidence that you have when you go through this process, that’s what makes so many people want to try it,” says Rodica Damian, an assistant professor of social-personality psychology at the University of Houston.

On the show, normal people open their homes to Kondo, who guides her clients as they sort through everything they own in a five-step process, beginning with clothing, before moving on to books, papers, Komono (miscellaneous) and sentimental. They struggle, sure, but over the course of the episode, they tackle not only their mountains of things but a series of existential and emotional troubles in their personal lives. And you can do it, too, Kondo assures viewers, in how-to segments she peppers into each episode.

Of course, people watching from the comfort of their couch will want in on this magic, Damian says. It’s human nature. Heck, she even tackled the KonMari method after stumbling upon the book back in 2015.

“It comes down to personality traits,” she says. “Conscientiousness is the broader personality trait, and that is basically how self-controlled you are, how able you are to regulate impulse, to be organized, follow instructions, to be hardworking and responsible.”

In our society, conscientiousness is a highly valued trait. Schools, the armed forces and employers all look for conscientiousness in recruits. People also seek this trait in their romantic partners and friends, whether they realize it or not.

“One of the facets of this trait is orderliness. So people want to tidy their house to feel that they’re an orderly person, to improve their reputation,” Damian says. “And then, their sense of identity gains because they see themselves as a more conscientious person.”

And here’s where the KonMari method seems to stick better than other New Year’s schticks:

“In cognitive behavioral therapy, if you want to change your personality, you follow a recipe of doing that behavior,” Damian explains. “To do that, you break down your goal into smaller goals and follow that recipe. And by doing that across time, that’s one of the ways therapy works. So once you’ve done that behavior enough, it can change your sense of identity and your reputation. So, you are what you do.”

So the five-step process, broken down into small stages, and implemented dutifully over an average of six months, is more than a Music Man pitch, if psychological reasoning is to be believed.

Armed with this kind of faith in the process, it’s no wonder Netflix bingers turn off their monitors and head straight to their closets.

Heidi Hoover had two bags of clothes ready to go before she even returned to work from the holiday, after watching the show in one super-sized serving on Jan. 1, when it launched, and immediately digging into the closets in her two-bedroom apartment near Memorial Park.

“I finished bingeing, and it was time to get to work. I’m like that. I get totally obsessed with something, and then I can’t do anything else,” she says on a Wednesday night as she readies her kitchen table to tackle the paper category, in which KonMari followers are told to gather every piece of paper in their entire home and sort through them, chucking all user manuals and instructions as well as paid bills, until all that’s left is actionable items.

“Clothes were the easiest. My clothes took like a day. I was like, ‘OK, clear off the table. Everything’s coming out,'” says Hoover, 45, who works in international trade and finance. “I really enjoyed it.”

Hoover watched only the Netflix special and has never read any of Kondo’s books, so her method was a little looser than the ones preached by Barber. After ditching the clothes she didn’t find joy in, Hoover turned to furniture.

As a recent transplant from New York, where she spent the past several years in a 425-square-foot living space, Hoover moved to Houston drunk on the promise of room to stretch. She leased a two-bedroom unit, which she filled with furniture from the Ikea just a short drive from her place.

“I have about 1,100 square feet here, and I feel like this is a luxury. And I went a little wild and had a two-bedroom that I didn’t need for two years,” she says, laughing as she points to an assortment of furniture she’s posted on Facebook buy-and-sell pages and on flyers in her apartment complex.

That’s the beauty of going through the Kondo cleanse, she says. She now sees the real motivation behind her purchases. And now she’s mindfully deciding what she really needs. Yes, it hurts to toss out things she spent her money on. But she chalks each item up to a lesson learned.

Kondo encourages people to hold an item in their hands and thank it before discarding it. And at first, that’s weird — both for people on the show with cameras in their faces and for people like Hoover talking to their socks alone in a two-bedroom apartment.

“At first, I kind of laughed about it. But now it’s very meaningful. It’s about looking at what you own and recognizing that everything has a purpose,” she says. Even if that purpose is just reminding you that just because you can have something doesn’t mean you should buy it.

With this in mind, she’s planning to downsize to a one-bedroom apartment when her lease ends in March. And she’s not anxious about giving up her luxurious elbow room. In fact, the idea of downsizing actually sparks joy in her.

This makes sense. Vida Yao, an assistant professor of philosophy at Rice University, says the KonMari method actually ties in well to one of the most prominent contemporary views on finding meaning in life, argued by philosopher Susan Wolf.

“There’s two important components to living a meaningful life,” explains Yao, who has watched a couple of episodes of the Netflix show but hasn’t become a Konvert herself.

The first component is “a subjective attachment to something,” meaning that you need to feel connected to something, whether it be a teddy bear or a dog leash. The second component is that this feeling of attachment needs to spark some kind of subjective response. For instance, joy.

By experiencing this two-part phenomenon, people can feel tethered to something. And that’s fertile ground from which someone can derive meaning in life, Yao says.

“It’s not like the tidying is what people care about. It’s the re-establishment of this subjective connection with things people already have,” she says.

So, if something “sparks joy,” as Kondo calls it, there’s a philosophical reason to keep it.

“A lot of my work is focused on what would it mean to have the right kind of response to something of value,” Yao says. “And what’s fascinating about the Marie Kondo phenomenon is, on the show, the people don’t have a problem with having valuable things they care about in their lives. They have loving relationships and activities they enjoy. But for some reason, the clutter is getting in the way of them feeling connected to things they care about.”

According to this theory, Smith’s conundrum on the floor in her home was never about the decision to keep or toss a bin full of Easter eggs. It was about asking herself whether the Easter eggs matter.

And it turns out, they really don’t. Normally, holidays are the kind of thing that spark joy for Smith. Before she dove into her binfull of eggs, she lovingly sifted through banners for birthday parties, candy accessories for gingerbread houses, her seasonal placemat stash and chose only her favorite birthday candles to keep. But this moment, right now, staring at the eggs, feels like a slog.

“You know what?” she announces after a few minutes of searching for matching egg tops and bottoms. “I’m just going to get rid of these.”

“Are you sure?” asks Barber, who is squatting at Smith’s right.

“Yes,” Smith tells Barber. “This isn’t … This doesn’t spark joy.”

She lets out a deep breath. That decision felt good. There’s joy in that.