By Nicole Brodeur

The Seattle Times

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) As Nicole Brodeur reports, Gates had been thinking about writing a book for four years. But it wasn’t until the #MeToo movement caught fire that she saw “this window, this opening in time” to talk about the greatest frustrations in women’s lives: Labor inequality, family planning, child care, income potential and the desire to be treated as equal partners. Respected.

KIRKLAND

In a building tucked into tony Carillon Point, voices are low and candles are lit. The bathroom is equipped for whatever could go wrong: a stain, a stray hair, something stuck in your teeth. There is sleek wood, white walls and lots of glass, behind which staffers — men and women, but mostly women — look up from their screens and smile.

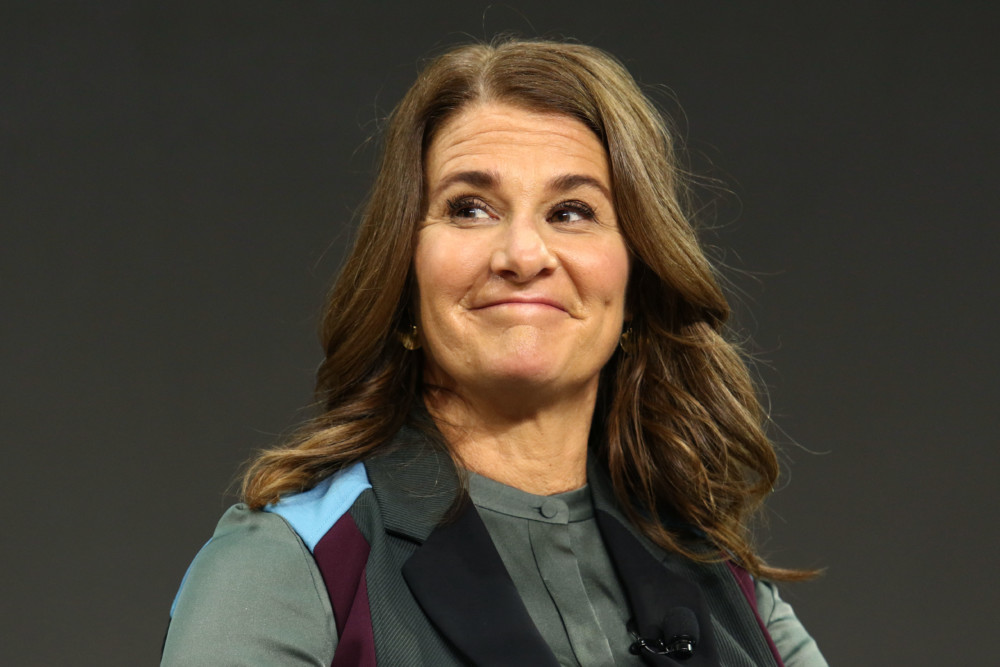

This is Pivotal Ventures, an “investment and incubation company” created by philanthropist Melinda Gates to attack the issues she has found most vexing. Paid leave for working families. Mental-health support. Closing the gender gap in tech. Providing venture capital to women-founded businesses.

But it is also a place where Gates can establish herself more fully, separate from her fame, her family and the work of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which she established with her husband, the Microsoft co-founder, in 2000.

Gates, 54, calls this “my house.” She had just emerged from a pocket door in the back of a meeting room that was more like a living room, filled with white-leather couches and family photos, a few awards and a fire going. Just outside the door, a table was stacked with copies of her new book, “The Moment of Lift: How Empowering Women Changes the World.”

The book — which Gates has been promoting with, among other things, an onstage chat with Oprah Winfrey and a sold-out, May 9 appearance at McCaw Hall — is a “roundup” of the things she has learned in 20 years of traveling for the foundation.

Those trips, taken with her husband, her children, and alone, have been spent administering vaccines, carrying water, winning the trust of villagers in the developing world. And listening. Lots of listening.

“What I tried to do was to take these women’s stories that you just don’t know you’re going to be the beneficiary of when you’re in the developing world,” Gates said. “When a woman opens her heart to you, and her home, and shares her life with you … I wanted to put those stories down in the hopes that they would call other people to action.”

The stories are contained in separate chapters focused on issues like maternal and newborn health, family planning, girls in school, unpaid work, women in the workplace. All the issues that Gates has lived and studied for two decades.

The book’s title comes from the space launches Gates watched growing up in Texas, the straight-A daughter of a NASA engineer: “There was nothing more exciting than the moment when the engines ignited, the earth would rumble and shake and then the rockets started to rise,” she said in a promotional video for the book. “The moment of lift. The moment we broke through gravity. That’s what I want to see for women and girls around the world. I want to see the forces pulling us up overpower the forces pushing us down.

“Because I believe when you lift up women, you lift up all of humanity. I believe that this is the moment. We are the lift.”

Gates had been thinking about writing a book for four years. But it wasn’t until the #MeToo movement caught fire that she saw “this window, this opening in time” to talk about the greatest frustrations in women’s lives: Labor inequality, family planning, child care, income potential and the desire to be treated as equal partners. Respected.

“I want to make sure that that window doesn’t shut,” she said. “That it’s not open for a short time. That we actually make huge progress for women around the world. And so it is a bit of saying, ‘This is what I have learned, and these are the places where we still need to go as a society for low-, middle- and high-income countries.'”

In telling these women’s stories, though, Gates also tells her own. How she joined Microsoft after attending Duke, and at a company event, took one of the last two empty seats at a table. Her future husband — and boss — took the other.

She wrote about how she didn’t want to move into that massive, state-of-the-art compound on Lake Washington that her husband had started building before they got married. (” … I was wondering what people would think of me, because that house was not me.”). How she felt alone in their marriage after the birth of their first child, Jenn.

“He was beyond busy,” she writes of her husband. “Everyone wanted him, and I was thinking, OK, maybe he wanted to have kids in theory, but not in reality. We were not moving forward as a couple to try to figure out what our values were and how we were going to teach those to the kids. So I felt I had to figure out a lot of stuff on my own.”

Her husband made her feel invisible, “even on projects we worked on together.” When a friend told her, “Melinda, you married a man with a strong voice,” it gave her perspective — and the desire to find her own voice and seek a more equal partnership.

It worked, in big and small ways.

The first time the Gateses wrote an annual letter for their foundation, she wrote, “we almost killed each other.” Bill Gates started writing it without his wife, even though much of what it contained they had learned together.

“It got hot,” Melinda Gates wrote. “We both got angry.” It took a few years — he writing one section, she another — but they now write the letter together.

Gates also writes of asking her husband to take over getting their three kids to school in the morning before work — inadvertently launching a fleet of fathers, prodded by their observant wives, to follow suit. (“If we ended up role modeling that one, hey, fantastic, right?”) She also became a more public co-founder and co-chair of their foundation “because we wanted people to know that it was both of us setting the strategy and doing the work,” she wrote.

That work included visits to developing countries, where she walked with village women to stand under trees to talk about their finances. She prepared meals in tiny cooking huts, carried water, stood out in the dust doing dishes at 10 p.m. She learned what the approach of rain smells like on the plain. She also spoke with women about their struggles to feed their families and prevent unwanted pregnancies.

The issue of birth control raised some conflicts with Gates’ Catholic upbringing, since the Catholic church teaches against contraceptives. “But there is another church teaching, which is love of neighbor,” Gates wrote. “When a woman who wants her children to thrive asks me for contraception, her plea puts these two church teachings into conflict, and my conscience tells me to support the woman’s desire to keep her children alive. To me, that aligns with Christ’s teaching to love my neighbor.”

Her time with these women taught her, humbled her, and enraged her.

“I have come out of the developing world both heartbroken, at times, and just angry at times,” she said. “And it’s that brokenness, that touching someone else’s life and understanding ‘That could be me.’ And sometimes it’s the other side of our emotions, which is our anger. And either one of them can fuel us to action.”

Gates remembered leaving places in Africa with one thought in her head: “If only.” If only women were more empowered. If only they had this or that policy. But Gates would learn that those wishes held true in the United States, as well.

Only 5% of Fortune 500 CEOs are women. Less than 2% of women get venture capital to fund their ideas. And women don’t even make up 50% of Congress.

“It will be at least 60 years, at this rate, until we have equality,” she said. “To me, equality matters. It can’t wait.”

There is hard work ahead, but Gates is pleased to have the work of the book behind her.

“Anytime you’re vulnerable, it’s difficult,” she said of the more personal passages. “But I chose to be because I thought that people could relate more to me and the stories of the other women in this book.”

She also wanted to show that her marriage, “like any healthy marriage,” has tension at times. But being able to wrestle with things is how you move forward.

“I have gone into several situations where people kind of allude to, ‘Well, it must all be fine for you because you’ve got a lot of money,'” she said. “No! It’s not all fine. Sometimes this stuff just needs to be worked through. I get asked so often — particularly early in the foundation’s years — ‘How in the heck do you work with your husband?’

“Well, you just have to work it out, you know? If you believe in equality, you have to believe in it in your home, in your community and in your workplace,” she said. “It’s what holds us to our better selves.”