By Rebecca Beitsch

Stateline.org

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) The topic of consent has been brought to the forefront especially by allegations against actor Aziz Ansari. The comedian recently made headlines after a murky sexual encounter with an unnamed woman that he says he thought was consensual.

WASHINGTON

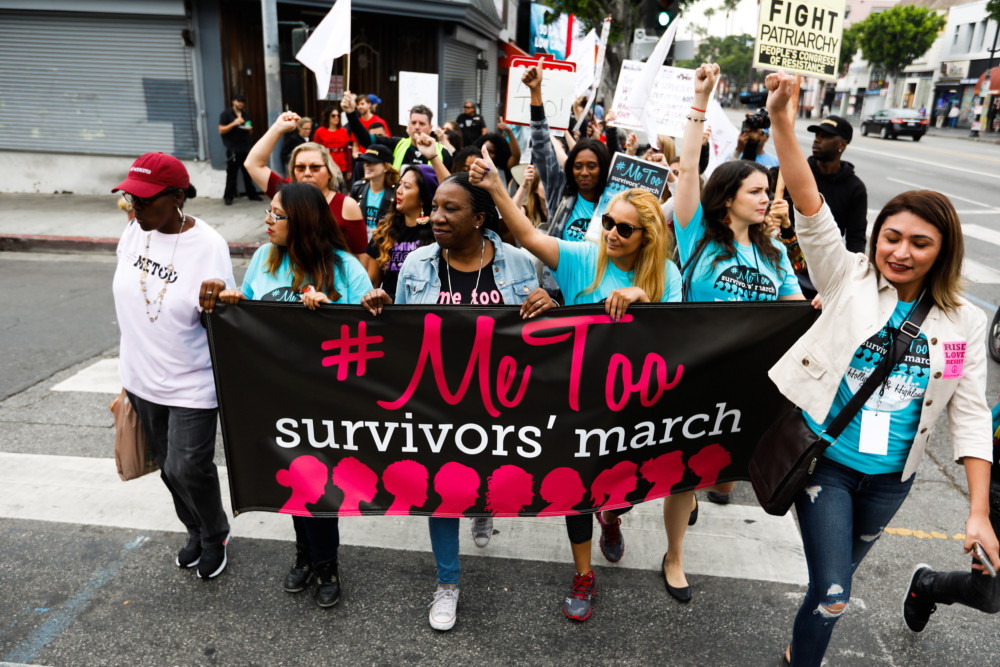

Fueled by accusations against titans of Hollywood, industry and politics, the #MeToo movement will prompt state lawmakers across the country this year to consider bills that could fundamentally change the culture of dating and sex.

States are expected to grapple with legislation to establish affirmative consent, known as “yes means yes”, and rewrite rape and sexual assault laws.

Legislatures already are considering more than two dozen bills that would strengthen laws against rape, teach students that both participants must consent to sexual activity, and extend the time to prosecute or sue those accused of sexual assault. They also will weigh measures to clarify sexual assault survivors’ rights, improve rape kit testing, and change the rules for sexual harassment settlements.

State lawmakers have debated such bills in the past. But this year a slew of accusations of sexual assault, misconduct and harassment, along with accounts such as the anonymous accusation against comedian Aziz Ansari, have given legislators greater momentum in pursuing policies that do more to crack down on abusers and support survivors.

The bills have been introduced primarily by Democrats, but many have Republican co-sponsors.

“I’m hoping we are just reaching a time where people realize this is not a fad,” said Maine state Sen. Mattie Daughtry, a Democrat who introduced a bill this year to teach consent as part of sex education. “There is a wave. This is women stepping up for change, and this cannot be put on the back burner.”

Legislators and victims’ rights advocates say many current laws put too much of the onus on victims, requiring them to prove they resisted sexual advances. And they say requiring victims to come forward quickly is unfair to those abused as children, who may take years to understand and grapple with what happened to them.

“The steady stream of people coming out and saying ‘me too’ led to this moment that I think is going to lead to a lot of change,” said Ilse Knecht, director of policy and advocacy with the Joyful Heart Foundation, a New York-based group that pushes states to improve rape kit testing.

Many states are considering bills that would toughen their existing rape statutes by no longer requiring proof that the perpetrator used force against his victim, or that the victim actively resisted.

“When you look at the neurobiology of trauma, we hear about fight or flight, but there’s a third response: there’s freeze. … Some women undergoing trauma, their body may choose to freeze,” said Washington state Rep. Tina Orwall, a Democrat who has sponsored a bill that would remove the force requirement from current rape law. “We don’t want victim-blaming. It shouldn’t be the victim’s fault for not fighting back.”

More than half the states have laws that require a show of force by either the perpetrator or the victim, according to a 2015 analysis of state laws by Deborah Tuerkheimer, a professor at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law who studies sexual assault issues. Only four states, Montana, New Jersey, Vermont and Wisconsin, have what Tuerkheimer considers a strict affirmative consent standard that requires both parties freely consent to sexual activity, rather than relying on the victim to say no.

The topic of consent has been brought to the forefront especially by allegations against Ansari. The comedian recently made headlines after a murky sexual encounter with an unnamed woman that he says he thought was consensual.

Tuerkheimer said those opposed to affirmative consent bills often argue that communication during sex can be a gray area and that too many would be punished for failing to meet a gold standard. But when she reviewed cases in states with an affirmative consent law, she found the types of rape cases being prosecuted did not differ greatly from those in other states.

“They’ve had these laws, and the sky has not fallen, and the cases that have been brought are the exact kind of cases we want prosecutors to bring,” she said of the states with existing affirmative consent laws.

In Nebraska, state Sen. Patty Pansing Brooks, a Democrat, introduced a bill that would scrap the force requirements for both perpetrators and victims in the current law while imposing a new affirmative consent standard.

“The old law didn’t do enough,” she said. “I guess the theory was, How could a woman not want sex? She has to prove herself she didn’t want it. … If you require that there be force, then someone has to fight off someone to say no. That’s not a reasonable standard.”

One of the most popular videos for explaining affirmative consent is a British public service video comparing sex to offering someone a cup of tea. If someone isn’t sure if they want tea, changes their mind about wanting tea, or passes out, the person who brewed the tea shouldn’t force it down the other person’s throat.

Pansing Brooks said she plans to send the video to all the legislators in her state, adding that she has heard some confusion on talk radio there, with hosts arguing it’s not always clear whether someone wants to have sex.

“‘How are we supposed to know?’ Well, ask her,” Pansing Brooks said. “It’s yes or no if you want to have sex. … You better be darn sure, or you could be liable.”

Some lawmakers are pushing for an affirmative consent standard to be taught in schools. Bills in Pennsylvania and West Virginia would make affirmative consent part of the code of conduct for college students. Bills in Maine and Michigan would require teaching affirmative consent as part of sex education in K-12 schools.

“Before MeToo, a lot of the conversation was about college campuses,” said Daughtry in Maine. “I think it’s critical to introduce it at an earlier age.”

State Rep. Abdullah Hammoud, a Democrat, sponsored the Michigan bill as a way to change the conversation around consent.

“I think what we’re trying to do is change a culture,” he said. “Personally I believe you change a culture with our youth. It’s important to provide that information and context at an early age.”

At least eight states, California, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Washington, Wisconsin and Vermont, also are considering bills that would extend the time for sexual assault victims to file a civil suit or for district attorneys to prosecute.

New York state Sen. Brad Hoylman, a Democrat seeking to extend the statute of limitations in the state, said current law protects abusers, particularly those who prey on children who may not address the issue before turning 23, as the law now requires.

“There’s this widespread revulsion among survivors that their abusers have remained unidentified and continue to prey on young people with abandon,” Hoylman said. “A constituent told me that he had been abused by his coach and shared that traumatic story with me but also added that wasn’t the worst thing to him. What was most outrageous was that his former coach was still at his school.”

Hoylman’s bill would extend both the criminal and civil statute of limitations going forward, and it also would create a one-year exception for people whose claims have expired to file a civil suit against their abuser.

Such windows have been used before in other states, despite claims from critics they would lead to a wealth of false accusations. Marci Hamilton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, studied the short-term windows used in five other states. Of those states, Hamilton said there was anecdotal evidence of only five false claims reported in California, out of 1,150 filed.

Still, such bills often face resistance in state legislatures. A bill to extend the statute of limitations in New York was voted down last year after hard lobbying from the Catholic Church, saying a one-year civil suit window would be financially devastating. And some prosecutors have also expressed concern, arguing older cases can be harder to prosecute.

Other state legislators are pushing the rights of victims of sexual assault and harassment.

Some lawmakers want to outline the rights sexual assault survivors have, often dubbed a bill of rights for survivors, and push stricter guidelines for how rape kits should be tested. Bills in New Hampshire and New York would forbid charging victims for a rape kit. An Iowa bill would require victims to be notified as their rape kit proceeds through testing.

“I think in the past these things were a matter of courtesy, and that didn’t work very well,” said Iowa state Rep. Marti Anderson, a Democrat who sponsored the bill there. “So I think they need to be in a law.”

California’s Legislature is considering a bill that would bar sexual harassment agreements from including a nondisclosure agreement that prohibits victims from speaking publicly about the harassment.

State Sen. Connie Leyva, the Democrat who sponsored the bill, said it was a direct response to the outpouring of allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein.

“What if that first woman he harassed and abused didn’t sign a secret settlement? Then maybe the 79 other women wouldn’t have been subjected to him and his ways,” Leyva said. “This takes the power away from the harasser and puts it in the woman’s hand.”

Leyva said the bill will primarily affect wealthy men who have long been able to keep their jobs and progress in their industry while the women they harass lose their job or struggle to advance in their career.

Leyva said there’s a simple way to think of it: “Pay us more. Touch us less.”