By Andrea Leinfelder

Houston Chronicle

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Grameen America is a microlender that helps low-income women entrepreneurs start and expand small businesses.

Houston Chronicle

Joann Poe spends her days repairing cables for a telecommunications company in New York City, but not earning enough to move above the poverty line. She’s hoping, however, not to stay there, using a series of small loans to grow a business that on evenings and weekends keeps her elbow-deep into Hennessy cognac cakes and Dr. Seuss-themed cupcakes.

With the help of four such loans, the largest at $2,500, Poe has moved her one-person company, NYC’s Best Dressed Cupcakes, from her home into an incubator kitchen, bought commercial equipment and started taking vegan baking classes (it is New York, after all).

Next, she’d like to hire employees and buy a refrigerated van.

“I have a different perspective on life,” said the 44-year-old Bronx resident. “I want to do more. Now, I’m thinking about what I’m going to do when I leave my full-time job.”

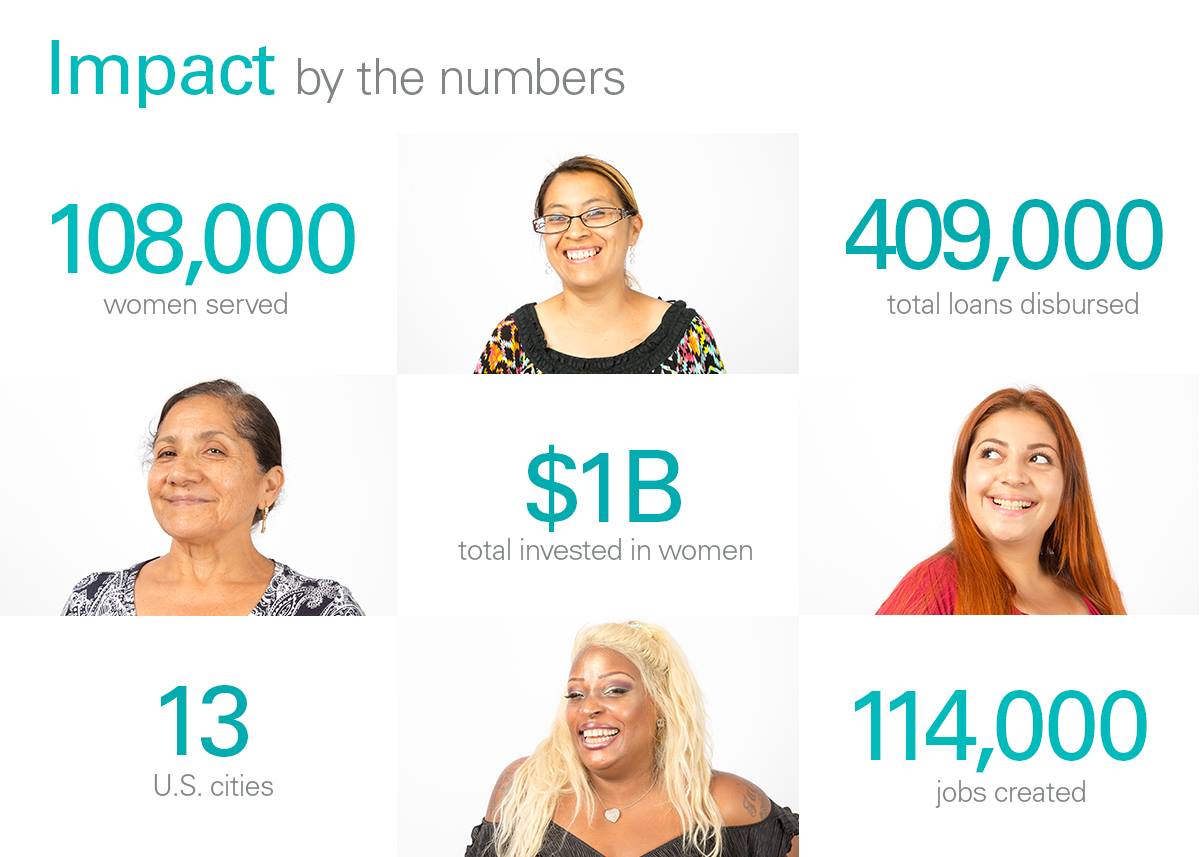

Poe’s financing comes from Grameen America, a microlender that recently expanded into Houston to help low-income women entrepreneurs start and expand small businesses. Grameen America, founded by Nobel Peace Prize recipient Muhammad Yunus who similarly founded Grameen Bank more than 35 years ago in Bangladesh, has disbursed more than $1 billion since opening in New York in 2008 and expanding to 21 U.S. locations.

Grameen America had Houston on its list of cities for expansion because of its concentration of underemployed women and families without access to banking services.

Andrea Jung, CEO of Grameen America, said 56 percent of people living in poverty are single mothers with children. The majority are women of color.

Also important was Houston’s entrepreneurial culture and a need for capital to support entrepreneurs.

Equal opportunity

And so while Grameen America had plans to expand into Houston, Hurricane Harvey and its impact on low-income families led the organization to accelerate its plans, Jung said. It has enrolled 35 women from Houston for its program.

“All of this, to me, is just about giving an equal opportunity,” Jung said.

Microlending, or microfinance, is based on the idea that small loans mixed with financial literacy and entrepreneurial attitudes can help lift people out of poverty.

In Houston, small-dollar loans can also be received from PeopleFund, which offers loans ranging from $1,000 to $350,000, Bayou Microfund, from $5,000 to $10,000, and LiftFund, with loans from $500 to $500,000 and higher with support from the Small Business Administration and banks.

Grameen America’s loans have an 18 percent interest rate and are repaid weekly over a six-month period.

An entrepreneur’s first loan will be no more than $2,000, with subsequent loans increasing in size up to $14,000.

The borrowers must take five days of financial literacy training before receiving their first loan.

They’re also required to meet with other women business owners each week to share best practices and receive coaching. And each woman in that group must repay her loan before any individual can get another loan, creating a social contract where the women are accountable to each other.

“It is that social capital and financial literacy training, as much as it is the loan capital itself, that makes the program successful,” Jung said.

But while microloans are a good alternative to payday lending, there’s a risk that borrowers could get trapped in a cycle of debt, said David Roodman, author of “Due Diligence: An Impertinent Inquiry into Microfinance.”

If the lender has one or two payments left, she may borrow money from a friend to pay off that loan — knowing she’ll soon receive a larger loan with which to repay the friend, Roodman said.

He also said these small loans may not reduce poverty levels to the extent some studies and advocates would suggest. Roodman analyzed what was once a leading study and found that the math made false assumptions, which overstated positive results. Several other studies found little evidence that microloans increase income.

“It can help some people, but it is not a transformative mechanism,” added Farhan Majid, with Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “One needs to really provide some complementary services to really make microcredit more effective.”

Jobs, income

These other services can range from vocational training to health care, said Majid, an economist who works on global health and development.

In addition to funding, Grameen America says it provides financial education and helps borrowers improve their credit scores. Soon after joining Grameen America, their credit scores reach an average of 640 — and provides access to mainstream financial services, such as no-fee savings accounts. Its Grameen Promotoras initiative provides health information and initiates discussions on topics ranging from improving nutrition to preventing domestic violence.

Grameen America said it has assisted more than 113,000 women and helped create 119,000 jobs. On average, women who participate in its programs increase their annual income by $1,500, the organization said. More than 99 percent of loans are repaid, and about 75 percent of women take out a second loan.

Susana Ugalde, 42, has received 16 loans. Grameen helped her after a tumultuous start to business ownership.

Prior to Grameen, Ugalde saved $22,000 over seven years to buy a beauty parlor in New York City. But she didn’t know that the business wasn’t properly licensed, and the city shut her down.

She lost everything but $6,000 or $7,000 in savings, which she used to start Susan Hair Salon in 2007 at a much smaller location in the Jackson Heights area of Queens. She had to borrow salon chairs from a friend and bring in mirrors from her home.

The loans from Grameen America allowed Ugalde to invest in her business, adding stations for manicures and pedicures, hiring additional employees and buying a new air conditioner.

Next step

Ugalde, who moved to the U.S. from Mexico more than 20 years ago, said owning a business has given her more time with family and has helped send her son to college. It even helped pay the fees associated with becoming a U.S. citizen in 2015.

Her husband is a small business owner, too, and they have a new goal on the horizon.

“The next step for my husband and me,” Ugalde said, “is maybe next year we can buy a house.”