By Michael Reschke

Herald-Times, Bloomington, Ind.

If you think stereotypes about gender and academic performance don’t matter, Kathryn Boucher would like you to check out the recently published results of her study.

They can be found in an article titled “Forecasting the Experience of Stereotype Threat for Others,” which appears early online in the May issue of the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

According to the article, not only do women perform worse when they’re concerned with negative gender-based math stereotypes, but both men and women wrongly believe those stereotypes won’t undermine their performance.

“Women and men both think if a woman tries really hard, she can find ways to cope,” said Boucher, lead researcher for the study and social psychologist at Indiana University.

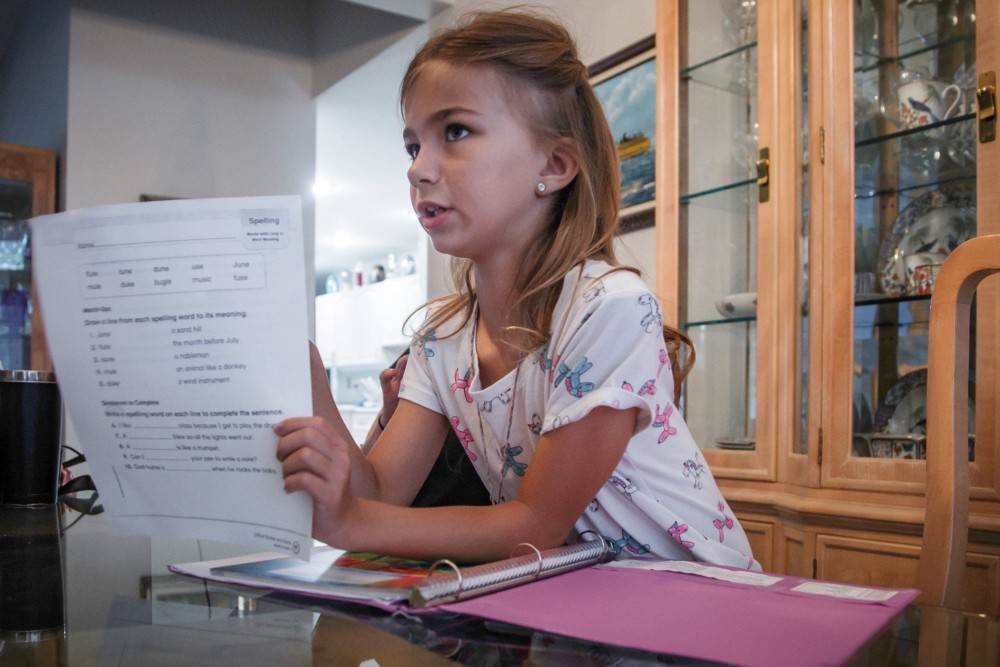

In the IU study, more than 150 study participants, split nearly evenly between men and women, were given 10 minutes to solve seven math problems on a computer with no scrap paper, according to a news release from IU.

Before completing the test, a negative stereotype about women was introduced by telling participants that the researchers were trying to find out why women are generally worse at math than men.

Half the participants were then told they would be asked to solve math problems, and they responded to a survey about their expected performance; the other half were told they would simply be asked to predict how they thought women might feel in this test-taking situation and how they would perform on the test.

The work confirmed earlier studies by finding that female test-takers performed worse and reported greater anxiety and lower expectations about their performance compared with men when negative stereotypes about gender were introduced at the start of the experiment. But the study went beyond previous research by also measuring men’s and women’s insights into the experience of the people actually performing under these conditions.

Boucher found that expectations did not match reality: While both sexes expected female test-takers to experience greater anxiety and pressure to perform under the influence of negative gender stereotypes, both male and female observers expected women to successfully overcome these roadblocks.

Boucher suspects several reasons for this assumption, such as living in a meritocratic society.

“We’re taught if we work hard enough, we’ll be able to succeed,” she said.

In addition, all of the men and women who were studied were college students.

“They had to succeed enough to get there,” she said. “They feel like everyone should have the ability.”

Evidence shows women do have the ability to succeed in math, but the anxiety of trying to disprove a stereotype undermines that ability. The gap in math performance between women and men in schools has decreased and in some areas does not exist anymore, Boucher said.

“Women, in middle school and high school, do just as well,” she said.

But believing negative stereotypes don’t have an impact could undo the progress that has been made in closing those gaps in performance.That could translate to reduced support for programs and policies that mitigate the impact of negative gender stereotypes.

Boucher said what she hopes people take away from the study is that if someone performs poorly on a test, they realize that stereotypes could be one possible explanation.

“I’m not saying it’s the only explanation,” she said. “But it has to be a cause that’s considered.”