By Heidi Stevens

Chicago Tribune

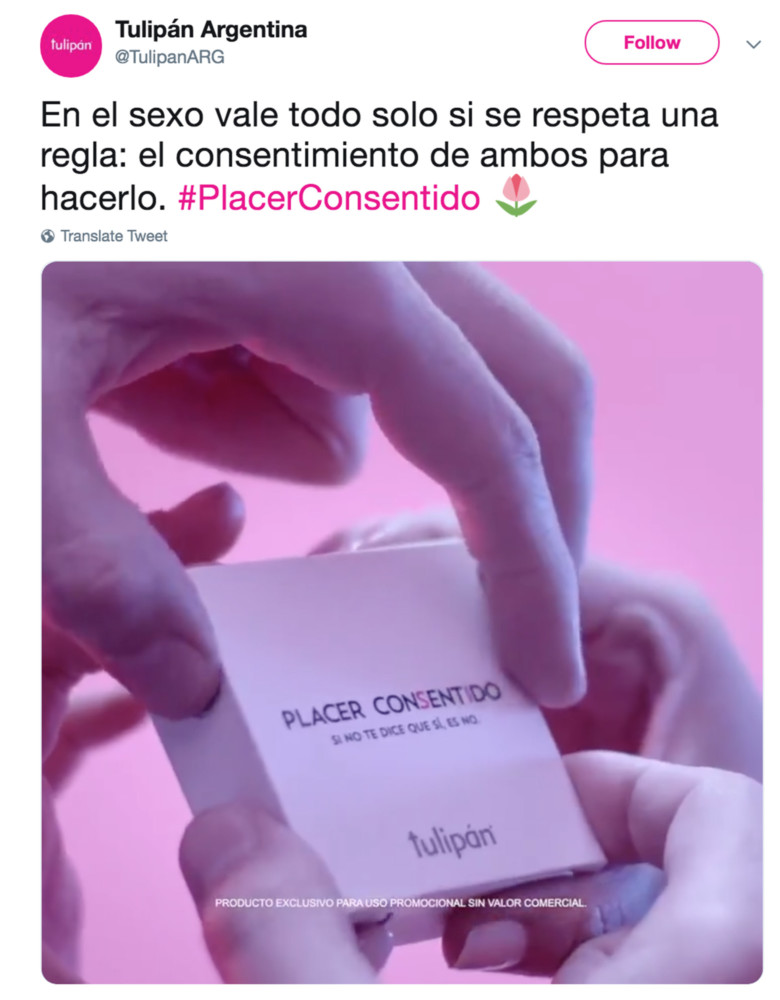

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) The “consent pack” requires that all four corners of the condom package have to be pressed at the same time for the box to open, which, in theory, requires two sets of onboard hands.

Chicago Tribune

A new condom package allegedly requires four hands to get it open, an attempt to place consent at the center of contraception.

“If it’s not a yes, it’s a no,” and “Without consent there is no pleasure,” read the taglines in a promotional video for the new “consent pack” of condoms, sold by Argentine company Tulipan.

All four corners of the package have to be pressed at the same time for the box to open, which, in theory, requires two sets of onboard hands.

People really hate the idea.

“I have seen & taken the (expletive) out of a LOT of products in my time,” tweeted Holly Baxter, editor for The Independent’s comment desk, “but the Consent Condom is definitely the worst one I’ve seen in 2019 so far.”

She wasn’t alone. Across the (internet) land, folks spent Wednesday trashing the idea as fumbling and misguided.

I called Chicago-based sex education instructor Kim Cavill to get her take. Cavill educates middle and high school students about safe sex and consent in Chicago and the suburbs.

“My immediate reaction was that it’s ableist,” Cavill said. “It makes the very large presumption that it’s two people who are going to have consensual sex, and those two people are going to be able to use their hands in a very specific way. Bodies move differently, and bodies move differently during sex.”

In addition, she said, consenting to open a condom doesn’t mean consenting to everything that happens from that point forward.

“It makes the assumption that consent isn’t able to be withdrawn,” Cavill said. “That’s not how sex works. People can change their mind.”

Some of the concerns raised included the fear that the product could be used to discredit victims of sexual assault. How could I have opened the condoms if I didn’t have a yes?

“That’s a totally legitimate fear,” Cavill said. “Sexual assault and forced sex are incredibly difficult to prove in a court of law, and it’s completely legitimate for survivors, like myself, and advocacy organizations who work with survivors to say, ‘You’re making an already difficult job that much harder.'”

Because, of course, hands can be coerced or forced into opening a package. Because making a condom even harder to access could mean the person coercing or forcing the sex just does so without protection.

And from a public health standpoint, Cavill said, the four-hands packaging takes a product that consumers already don’t use often enough or properly and makes it harder to access.

“The main issue with condoms has always been compliance,” she said. “Condoms work really well if they’re used consistently and correctly, and this doesn’t make sense if you look at the barriers that already exist to condom usage.”

Her students, Cavill said, need to be taught never to use their teeth or scissors to open condoms. They ask whether they should wear two. They ask how to access condoms if they don’t have the money to buy them.

“If we’re going to have a conversation about condoms and consent and correct condom usage, I wouldn’t be starting the conversation with a condom that requires two people to open it,” she said. “I’d start with freely available comprehensive sex-ed in all high schools, allowing condom demonstrations with explicit directions, making condoms and contraceptives much more widely available. I suppose, in theory, if all those things happen, then years down the line we can talk about your weird condom idea.”

For now, Tulipan, a company that sells sex toys and sexual health products, is placing the condoms in bars, clubs and social events around Buenos Aires, Argentina, and plans to sell them online in the future.

In the meantime, the social media campaign is stirring up debate about whether similar products will, or should, launch elsewhere.

Cavill wasn’t interested in trashing the new product.

“Failure is a teacher,” she said. “I like the learning that can come out of the conversations we’re having. But with the product itself, I remain thoroughly unimpressed.”

The “consent pack” is not unlike apps that have been developed to encourage (and digitize) consent, Cavill said, in that it signals our collective entry into territory we have traditionally avoided, talking about and teaching about gaining consent.

“We’re having brand new conversations we’ve never had before, and because they’re brand new, they’re really clumsy,” she said. “That, to me, is where this fits into a larger conversation.”

Talking and openly communicating your desires and boundaries before and throughout any sexual encounter remain the best ways to approach sex, she said. Teaching those skills from an early age remains the best way to encourage consent as a lifelong value to protect and uphold.

“Consent needs communication,” Cavill said. “Whittling it down to putting your thumb on a phone or opening a condom as though that covers the bases, no.

“This is a silly idea,” she said. “I have a lot of criticisms about it. But I’m glad the product was made, because we’re having conversations about it. And those are conversations we need to be having.”