By Sarah Breitenbach

Stateline.org

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Massachusetts, where women earn 83 percent of what men make, a slightly narrower wage gap than the national average, passed the first state law that prohibits employers from asking for job candidates’ salary history. A similar measure is expected to be introduced in the U.S. Congress.

Stateline.org

To prepare for asking her boss for a raise, a woman might want to try negotiating for a free breakfast each time she stays at a hotel.

Practicing negotiation skills like this could help women navigate high-stakes requests at work, where they are less likely than men to request raises or promotions and are more often turned down when they do, said Megan Costello, director of Boston’s Office of Women’s Advancement.

She hopes to bring negotiating tips, like asking for free breakfast, or wheeling and dealing over meeting times with colleagues, to 85,000 of the city’s women through a free two-hour training course on how to negotiate in the workplace.

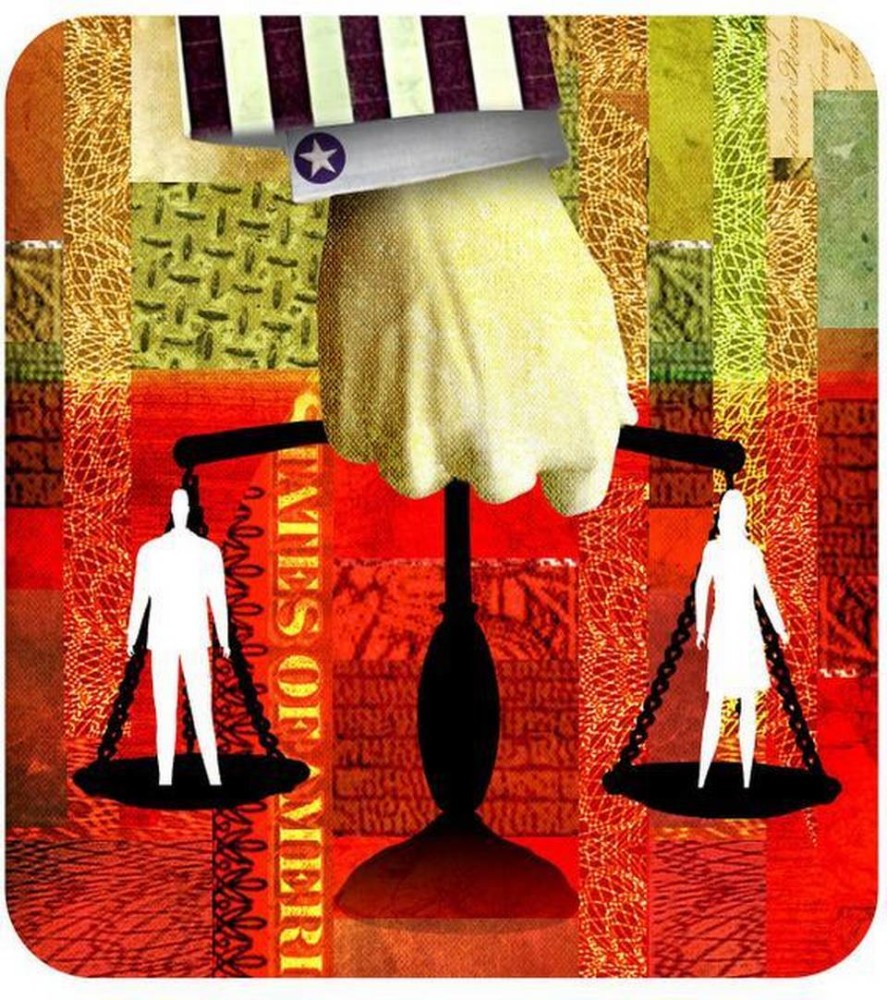

It is just one way the city is trying to whittle away a national salary gap that leaves female workers making 80 percent of what their male counterparts earn, a gap that could take more than a century to close.

And it’s another way state and local governments are attempting to reduce the gap, in addition to mandates on employers and protections for workers, while a proposed Paycheck Fairness Act that would expose employers to lawsuits if they offered different salaries for comparable work for reasons other than education and experience remains stalled in Congress.

“We’re seeing states like California and Massachusetts and Maryland pass bills that have a lot of similarities to the Pay Check Fairness Act, and we can see states act as pilots and incubate different ideas,” said Kate Nielson, a policy analyst with the American Association of University Women, or AAUW, a nonprofit that promotes education and equality for women and girls.

Massachusetts, where women earn 83 percent of what men make, a slightly narrower wage gap than the national average, passed the first state law that prohibits employers from asking for job candidates’ salary history. A similar measure is expected to be introduced in the U.S. Congress.

The Massachusetts bill also requires men and women be paid equally for the same work and protects workers from retaliation for discussing how much they get paid.

Groups like the AAUW say deciding how much to pay workers based on what they previously earned hurts women because they were likely paid unfairly in their former jobs.

But opponents of the bill argue that it replicates existing state law, that it won’t reduce the wage gap, and that it likely will hurt small businesses.

The inability to ask about a potential worker’s past compensation creates a liability concern for small businesses because potential employees might disclose their existing salary anyway, putting a company in violation of the law, according to Elizabeth Milito, a lawyer for the National Federation of Independent Business.

“I think, a lot of times, applicants are going to say, ‘I’m making X amount, so that’s what I need, to come and work for you,'” she said.

This type of legislation also presumes that pay differentials are caused by intentional discrimination, Milito said; and opens new avenues for lawsuits against business owners.

More than any other state, New York has narrowed the wage gap. But even there, women only make 89 percent of men’s earnings. No state has been able to close the gap for women completely, but Minnesota has eliminated the pay gap for women in the public sector.

The state requires its government, at the state and local level, to track salaries for all public sector workers who do comparable jobs, including teachers, and to raise wages if salaries do not match.

But researchers in Minnesota, where women on the whole make 81 percent of men’s income, say closing the gap completely will be impossible until men and women are equally represented in all types of jobs.

This year, at least 36 states introduced and several passed legislation to narrow the gap.

Maryland now prohibits employers from “mommy tracking,” directing female employees into less-favorable career paths, or not telling them about promotions or opportunities to advance.

Delaware barred employers from prohibiting discussions about wages or punishing workers who want to talk about how much they earn.

And Nebraska and Utah updated their equal pay policies to apply wage discrimination laws to more businesses and increase the damages employees can seek in those cases, respectively.

In California, three wage gap bills are in front of Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown. They would prohibit employers from using prior salaries to justify a disparity in compensation, compel state contractors to show they are following antidiscrimination laws, and keep employers from paying workers less based on race or ethnicity.

Last year, California decided that women could sue their employers over pay disparities for “substantially similar work.”

Previously courts had ruled that such suits were only eligible when a man and woman were being paid differently for the exact same job.

But in North Dakota, where a 2015 law ensures employers can’t retaliate against employees who discuss wages or bring complaints and allows for class actions lawsuits against employers, Republican state Sen. Judy Lee said legislation beyond what already exists at the federal level is largely unnecessary.

“It’s not that it never happens,” Lee said of women making less money than men. “I just think the idea that it happens organically, over everything, systemwide, is just ridiculous.” Because women do make choices that impact their careers, Lee said.

Lee questioned census numbers used to determine the wage gap, saying the data is skewed because it does not compare salaries of comparable jobs.

In 2015, the gap in North Dakota, where women earned 71 percent of what men made, was the third biggest in the country.

Women may also get paid less because they choose to work fewer hours than men, Lee said; or because they pick career fields with traditionally lower salary ranges.

“If I was the boss and somebody was putting in extra effort and that was important to me, then they might be promoted, they might be receiving additional compensation, whatever it might be,” Lee said.

Milito agrees and said wage disparities can be attributed to women who take time away from work, work part time or on flexible schedules, or take time off to care for a loved one.

But pinning the wage gap on choices women make, whether it’s taking time off to stay home with young children, or working in a lower-paying, female-dominated field, such as teaching or home health care, doesn’t account for the whole difference in pay, the AAUW’s Nielson said.

She points to an AAUW study that examines the wages of college graduates one year out of school. Even after controlling for factors like college major, level of education, number of hours worked, months employed since graduation and type of job, the study still found a 7 percent pay gap between men and women.

“That 7 percent gap really can’t be explained by anything other than discrimination,” Nielson said.

Census data show the gap narrowed only by a percentage point between 2014 and 2015, and women’s median pay has hovered just below 80 percent of men’s wages for the last decade.

Eliminating the gap would require a combination of training programs, like Boston’s, legislation that forces employers to address and prevent pay disparities, and shifting a culture in which women are often directed away from careers in math and science and leadership positions, according to Costello, who runs the Boston program.

Once they are in the workforce, women are less likely to negotiate for a higher salary when applying for work unless a job description explicitly states that wages are negotiable, a Harvard study on salary negotiations and the pay gap indicates.

Though Costello’s program has taught 1,500 women how to negotiate their salary in the last year, she is still collecting data to measure the program’s success. She expects to have results in the spring. But anecdotally, she said, her advice is paying off.

“We’ve heard stories of ‘I got a 40 percent raise,’ or ‘I got the promotion I was looking for because I felt empowered to ask.'”