By Leah Thorsen

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

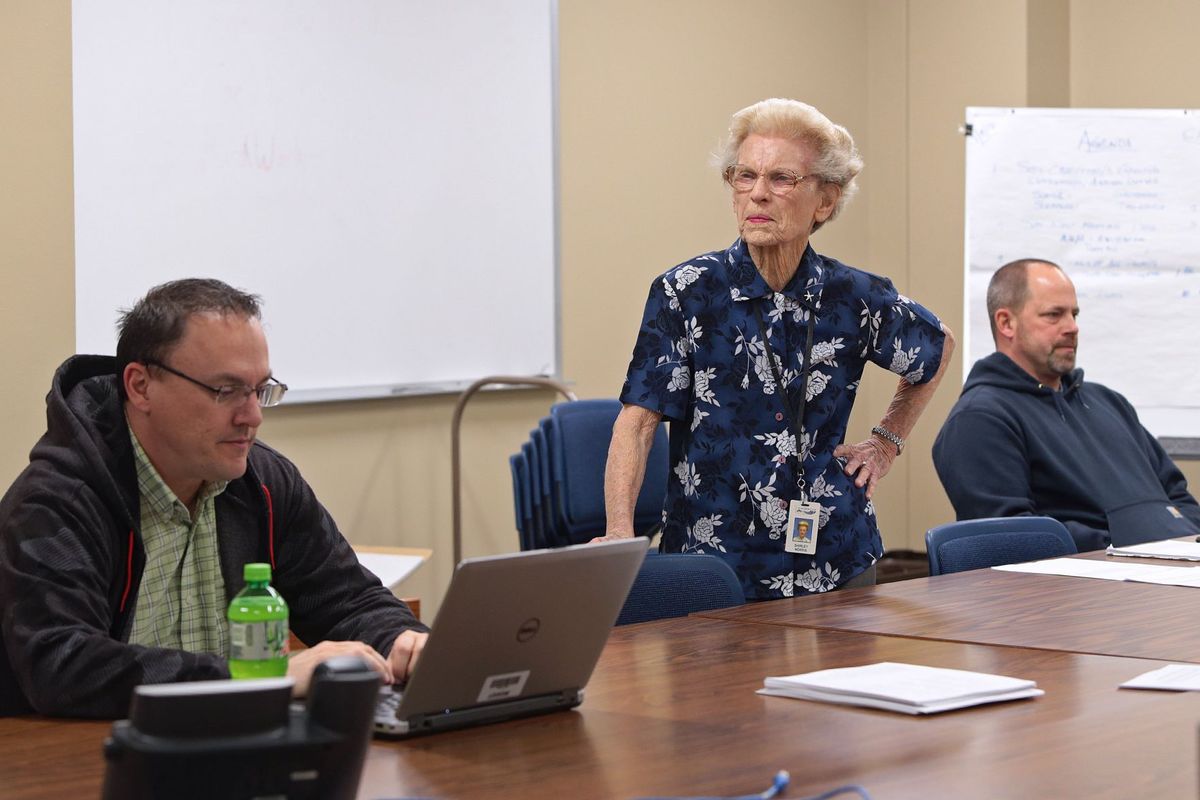

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) 87-year-old Shirley Norris is the Missouri Department of Transportation’s oldest employee. She’s the project manager for Jefferson and Franklin counties, which means she’s in charge of getting contract plans out for bids and making plans long before drivers see work being done. In the last couple of decades, she has overseen laying the groundwork for roughly 250 projects totaling more than half a billion dollars, according to MoDOT.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

When Shirley Norris began her studies at Vanderbilt University in 1947, she was one of three female engineering students in her class.

The dean of the engineering school made it clear the women had to prove they could keep up at a time when World War II veterans using G.I. Bill benefits were filling classrooms, and he wasn’t subtle.

Norris remembers what he said: “If you young ladies can’t cut the mustard, there are veterans who can.”

They all made it. The other women became electrical and chemical engineers, and Norris, who said she learned a lot from those veterans, became a civil engineer.

It’s a job she has no plans to give up — the 87-year-old is the Missouri Department of Transportation’s oldest employee.

She’s the project manager for Jefferson and Franklin counties, which means she’s in charge of getting contract plans out for bids and making plans long before drivers see work being done.

In the last couple of decades, she has overseen laying the groundwork for roughly 250 projects totaling more than half a billion dollars, according to MoDOT.

She could have clocked out about 20 years ago under the state agency’s “80 and out” system, in which employees are eligible to retire after the combination of their years of work and age equal 80.

“I never even checked it,” she said of her retirement qualification in a recent interview in her MoDOT office in Town and Country.

Foot in the door

Norris grew up in south St. Louis and graduated from Southwest High School. She loved science and math, and her father, who operated salvage yards, supported her pursuing an engineering degree.

She applied and was accepted to Northwestern University and to what’s now the Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla. But Vanderbilt rejected her, which made her determined to go there, she said.

Norris calls her eventual admittance there to being in the right place at the right time — a well-connected man’s daughter had been accepted, making it hard for the university to refuse her.

Several colleges still weren’t allowing women into engineering schools even in the 1970s, said Jessica Rannow, president of the Society of Women Engineers.

“She definitely would have been quite the trailblazer,” Rannow said of Norris.

And she still is. Today, women make up only 11 percent of practicing engineers, according to a study that Rannow’s group released last spring.

After Norris graduated from Vanderbilt, she came back to St. Louis and worked for the engineering firm Sverdrup & Parcel for about a year. It was before calculators, and her job included helping develop tables to determine the stresses on elliptical joints.

She quit working after marrying her husband, a chemical engineer. He took a job with Union Carbide and they moved to Oak Ridge, Tenn., and then to Rifle, Colo.

Then in 1964, when she was 34, her husband was killed in a car crash. She was a widow with two children, ages 7 and 9. After his death, she stayed in Colorado, where she did some work for local surveying companies, as well as a lot of volunteering. She remarried and had another child before a divorce, and moved back to the St. Louis area in 1971.

She got part-time work in the evenings at a paint store, and did drawing-board work for $2.15 an hour for a company that designed steel girders for bridges.

“I realized I was going to need more than that,” she said.

It was her son who said to put her engineering degree to use, and her father who pushed her to apply at what’s now called MoDOT.

She was hired in 1977, when she was 47, in an entry-level engineering position.

“I was elated,” she said.

After seven years, she was promoted to the position of squad leader, which meant she supervised the design team — the first woman in the St. Louis district to earn that rank — before becoming a project manager.

Lessons learned earlier in life helped her in those roles, including a meeting with a college professor who balked at telling jokes he thought too salty for women to hear.

So Norris made an appointment to see him.

“I told him, about the jokes and the punch lines — I probably heard those when I was 6 years old.”

That education came from a grandma who was an avid baseball fan and who listened to games on the radio in her rocking chair.

“When I came into work with a bunch of men, they soon figured it out,” she said. “Those lessons really have benefited me in my life.”

These days, her workload includes getting the wheels in motion for a resurfacing project on Interstate 55 south of Pevely down to the St. Francois County line that includes rehabilitating 21 bridges. The $19 million project is expected to begin this spring.

She said she tells her bosses to let her know when she’s no longer keeping up with her full-time job. That hasn’t happened, and she has no plans to retire.

“I just don’t know what else I would do,” said Norris, of Affton. “Right now, all I want to do is my job.”

A few years ago, she fell on ice and broke her hip. She was back to work in a month. Her daughter took away her work computer when she was in the hospital, but she used it while going through rehab to keep her sanity.

She wanted to get back to normal.

“Normal for me is working.”