By Mary Beth Breckenridge

Akron Beacon Journal.

AKRON, Ohio

You’ve probably heard of Louis Comfort Tiffany’s stained-glass lamps.

You may even be familiar with some of his more famous lamp styles, such as the Wisteria and the Dragonfly.

But you may not know those lamps were designed not by Tiffany, but by a woman who came from Tallmadge, Ohio.

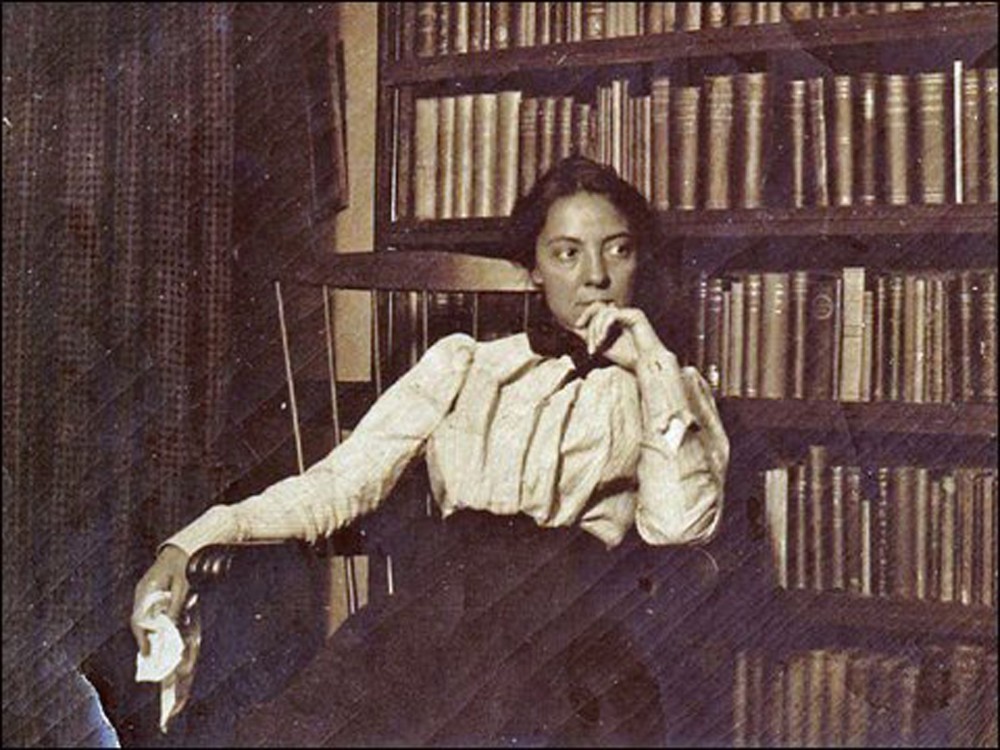

Clara Wolcott Driscoll was the creative force behind many of Tiffany’s most successful designs.

Around the turn of the 20th century, she led a group of female artisans who designed and cut the glass for many Tiffany lamps, and she personally designed some of the most valuable Tiffany lamps as well as some other decorative objects his company made.

Yet for the most part, she did it anonymously.

Driscoll’s importance to Tiffany’s success went largely unrecognized until less than a decade ago, when a couple of historians stumbled separately on evidence of her role.

Their discoveries led to an exhibition on Driscoll and her staff called A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls, which was created by the New-York Historical Society and has since traveled as far as Germany and the Netherlands.

To Linda Alexander, it’s a story made for Hollywood.

Alexander is a fourth cousin of Driscoll’s and a genealogy buff who has immersed herself in her cousin’s colorful life.

The Stow, Ohio, resident has been giving presentations locally on Driscoll since 2007 in the hope of boosting the profile of a woman whose contributions went mostly unnoticed during her own lifetime.

Alexander said her audiences typically respond with amazement at Driscoll’s story and the twists of fate that brought it to light. “It needs to be a movie,” she said.

Driscoll was born in 1861 in Tallmadge and grew up in a house on Northeast Avenue that still stands.

She graduated from design school in Cleveland and later moved to New York to study architectural decoration at the Metropolitan Museum Art School.

Around 1888 she joined Tiffany Studios, started by Louis C. Tiffany, whose father founded the famous Tiffany & Co. jewelry store.

Her on-again, off-again employment at Tiffany Studios lasted 20 years.

This was the 19th century, when married women were expected to stay at home, Alexander explained.

So marriage, and in one case, marriage plans, forced Driscoll to quit her job three times.

Twice she returned, once after her first husband died just three years into their marriage, and a second time after her fiance got cold feet and disappeared. (He turned up five years later in San Francisco, claiming amnesia, but by that time Driscoll apparently realized she’d dodged a bullet, Alexander said.)

Her final departure was permanent.

Driscoll left Tiffany for good in 1909 when she married her second husband, Edward Booth.

She died in 1944 at age 82, and her ashes are buried in Tallmadge Cemetery.

At Tiffany, Driscoll headed the women’s glass-cutting department and was the principal designer.

She often based her designs on nature, Alexander said, sometimes asking family members to send her flowers from Tallmadge to inspire her work.

Even though her contributions were unknown to most outsiders, Driscoll was apparently a canny businesswoman in a man’s world, Alexander said.

She faced opposition from male workers who were unhappy with the influence wielded by her all-female department, but she apparently handled those disputes deftly.

Once, Alexander said, she lightened the atmosphere of a contentious meeting by showing up with a couple of quarts of ice cream.

The feisty Driscoll was respected within the company and paid well for her work.

A 1904 article in the New York Daily News about highly paid women noted she earned more than $10,000 a year, a salary that would translate to more than $250,000 today.

But apparently, Louis Tiffany didn’t like sharing the limelight.

His company’s records were lost after it closed in the 1930s.

Her contributions might never have been known publicly, in fact, if it weren’t for her family’s prolific letter-writing.

Driscoll, her sisters and a few other female relatives kept up with one another through a round-robin correspondence that went on for years, Alexander said.

They would write long, newsy letters, each of which would be passed among all the women and eventually returned to Tallmadge to be saved.

After Driscoll’s sister Emily Wolcott died in 1953, 1,163 of the letters were found in Wolcott’s summer cabin and eventually donated to Kent State University, Alexander said.

Another 167 were found in the attic of a house Wolcott once owned in Queens, N.Y., and donated to the historical society there.

The letters paint a remarkably complete picture of Driscoll’s job, describe her travels and her active social life in New York, and even contain drawings of the some of the lamps she’d designed.

Still, interest in the letters’ contents was pretty much limited to a few family members until about nine years ago, when a couple of historians independently got wind of them, one of them tipped off by a third cousin of Alexander’s.

The historians made an almost unheard-of agreement to collaborate, and their research eventually led to the exhibition on Driscoll.

“It just rocked their world,” Alexander said of the historians. “And it pretty much rocked the art world. … No one knew there was a woman behind these lamps.”

In her way, Alexander is out to right a wrong, to give Driscoll the recognition she never got to enjoy.

“I feel badly that she never had a voice,” she said. “… I’m going to help get her name out there.”