By Dustin Hockensmith

pennlive.com

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) As Dustin Hockensmith reports, “There’s a huge movement across the country to get every state to recognize the sport and satisfy a growing demand from girls to have the same opportunities as boys.”

Pennlive.com

If 12-year-old Adalynn Smith were a boy, she would be expected, maybe even encouraged, to follow in her father’s footsteps.

Her dad, Adam Smith, a former state champion wrestler from Newport and one of the greats in Perry County history, has immersed himself in wrestling his entire life. After high school, Smith qualified for three NCAA tournaments, was a team captain at Penn State and went on to work for the Nittany Lions program.

But when his daughter said she wanted to wrestle, he wasn’t sure how he felt about it.

Adalynn said she’d watched her dad teach private lessons and fell in love with the sport. She persisted for years and eventually succeeded in getting to wrestle – with one condition.

“We were just more concerned and said, ‘We don’t mind if you wrestle, but we want you wrestling girls,’” Adam Smith said.

She wrestled at a novice girls’ tournament at Newport High School Sunday. One of the few opportunities available to girls, it attracted about 60 wrestlers, from kindergarten to high-school age – from as far as Wyoming Seminary, the Lehigh Valley and Central Mountain High School.

“If you want to be a female novice wrestler coming into the sport, it’s really, really limited right now,” Smith said. “You’re going to be a) wrestling boys or b) traveling a good bit.”

“My ideal outcome is not for her to be wrestling boys,” Smith said. “I don’t think it’s spectacular for either the girl or the boy, specifically the older you get. It’s hard to get a winner in that situation.”

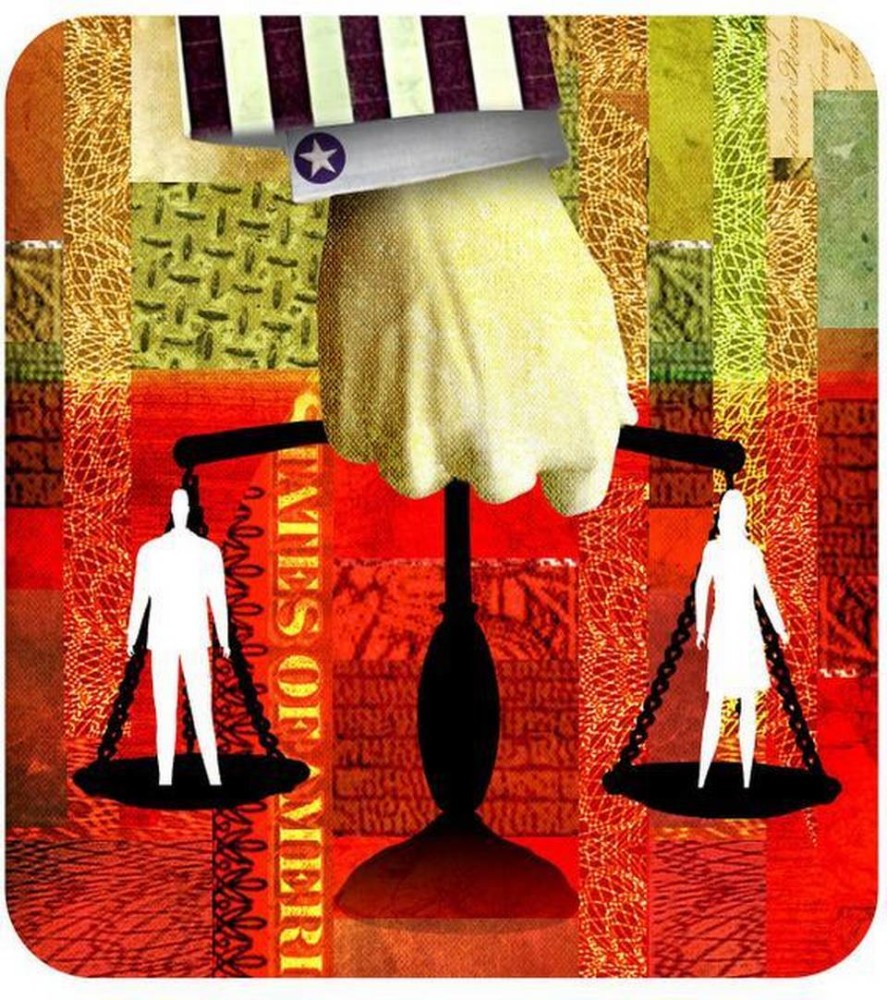

Pennsylvania is one of 31 states that does not yet recognize girls’ wrestling as a sport, which leaves girls with two choices: wrestle with boys or not at all.

It’s a complicated decision for families of girls who are interested in the sport. Women’s wrestling is the fastest-growing sport in the United States, with 21,124 women wrestlers last year, an increase of 242% from 2013.

But the future of girls’ wrestling in Pennsylvania is cloudy.

Some coaches say they are worried that Pennsylvania, a national leader in wrestling, is falling behind other states that are moving forward with programs for girls. Critics say Pennsylvania’s governing body of high school sports must do more to promote opportunities for girls’ wrestling.

Last season, the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association said, 206 girls participated in wrestling at the varsity level, spread over 450-plus schools. Advocates and many coaches believe the number would grow exponentially if girls’ wrestling were recognized as its own sport.

There’s a huge movement across the country to get every state to recognize the sport and satisfy a growing demand from girls to have the same opportunities as boys.

“The value of this sport transcends gender,” said United States women’s national team coach Terry Steiner. “Why would we want to limit it to half the population?”

Girls’ wrestling grew 27.5% from 2018 to ’19, according to USA Wrestling figures. Georgia, Oregon, Missouri, Maine, Massachusetts and New Jersey all held official girls’ high school championships for the first time.

Nationwide, 19 states held tournaments for girls wrestling last season, up from six in 2014, and other states made progress in that direction.

Arkansas offered no wrestling at all for boys or girls before 2008, but somehow jumped ahead of Pennsylvania on the girls’ side.

“Arkansas beat Pennsylvania to the punch in something in wrestling,” historian and Hall of Fame writer Jason Bryant said. “That right there should tell you something. All it takes is to open the doors, because Pennsylvania would dominate pretty quickly.”

That begs the question: Why is one of the national leaders in the sport not acting faster to create more opportunities for girls?

“We consider ourselves at the forefront when it comes to wrestling, but that’s obviously an area we’re lagging behind,” said Biff Walizer, the varsity coach at Central Mountain and a former All-American at Penn State. “And that’s unfortunate to see other states take the lead when I consider Pennsylvania to be the No. 1 high school wrestling state.”

CHICKEN AND THE EGG

Bob Lombardi, executive director of the PIAA, and Mark Byers, the chief operating officer who oversees wrestling, liken the argument for girls’ wrestling to the chicken and the egg. Which should come first, sanctioning the sport to grow participation or proving that enough interest exists to warrant action from the PIAA?

That question also must be asked in the context of the PIAA’s bylaws, Lombardi said.

Those rules dictate that 100 schools must sponsor the sport before they can consider it. Sponsorship means appointing a coach, setting a practice schedule, and using at least half the PIAA’s allotted points for competition.

The PIAA exists to serve its membership, Lombardi added, and the numbers at the varsity level simply don’t yet warrant action.

“You need to pass the fertilizer around the local areas and start seeing more people in the wrestling rooms and more participation, and we’re not seeing it,” Lombardi said.

“The advocates are out there, ‘Oh, yeah, you can change it and do it a different way.’ That’s not an easy sell to schools.”

Chris Atkinson is the head wrestling coach at Souderton High School and one of Pennsylvania’s most avid proponents of girls’ wrestling. Until recently, he served as women’s director for Pennsylvania USA Wrestling. Atkinson said a recent meeting with Byers revealed a hard truth about the PIAA’s stance.

“That was like a road block,” Atkinson said. “It was like, ‘Wait a minute.’ It was a killer for us. Pennsylvania has a backwards model. They want proof that the numbers are there before they go ahead and sanction the sport.”

Nazareth coach Dave Crowell is one of the most successful high school coaches in Pennsylvania history, as well as a member of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He respects the PIAA’s position but agrees that the chicken-and-egg argument needs to be flipped.

“Right now, I can see from the people making the decision saying, we have to wait until we get enough girls,” Crowell said. “The problem is, unless they see an opportunity, you may not get the girls. So, how do you go about doing this thing? I personally think you’ve got to offer it first.”

The logistics are far from clear on steps to move forward. How will the competition work? If a school does sponsor a girls’ program, how would they compete, and against whom?

There are also resource issues to resolve in every high school, and the proper push might start right there, Lombardi added.

“A lot of the questions can be answered locally,” Lombardi said. “Top-down isn’t going to work here. It really needs to be a grassroots movement.”

‘RELUCTANT TO CHANGE’

The PIAA has been clear on its position from the outset, but advocates ask: Isn’t feeding wrestling’s biggest source of growth worth a deeper look?

There’s also an enduring criticism that the PIAA is too slow to move and too resistant to change and that it is passing the buck to schools instead.

Ronnie Perry is a former NCAA runner-up at Lock Haven who went to Solanco High School. In May, Lock Haven announced that Perry would lead the launch of a women’s program.

The idea was to beat the competition to it, the reverse of the PIAA’s approach. Lock Haven wanted to not only announce its launch, but to do it as quickly as possible.

“Obviously, I think the PIAA is a little reluctant to change,” Perry said. “In order for the women’s side of wrestling to grow, it needs states like Pennsylvania on board with women’s wrestling. It’s a national leader in men’s wrestling and has world-renowned college programs in the state. It’s a must for them to get the sport added and sanctioned.

“I feel like they’re hurting themselves by not adding it. I feel like if they add it, they’re going to see a little bit of an explosion in participation. It could be parents don’t want their kids to wrestle guys or it could be the girls themselves. If you sanction women’s wrestling, you’re going to get more participants at an earlier age. Someone’s got to pull the trigger first.”

When other states have sanctioned programs for girls, participation has surged.

Missouri went from 169 girls in 2017-’18 to 910 last year when girls’ wrestling was added. New Jersey went from 124 to 445, Georgia from 238 to 516, and Arizona from 286 to 543, according to USA Wrestling figures.

The PIAA isn’t turning its back on girls’ wrestling, said Pat Tocci, senior director of the National Wrestling Coaches Association. Now, it’s about executing that grassroots plan by talking about girls’ wrestling more often, bringing the subject up in coaches’ meetings, creating more club events, and spreading the word at the local level.

“I think the PIAA has been clear on what needs to be done,” Tocci said. “You can look at it and say, ‘They’re throwing up all kinds of roadblocks,’ or you can roll up your sleeves and do what needs to be done. You continue to build and grow to that 100-team threshold. I don’t think it’s nearly as daunting as it might seem on the surface.”

‘LET’S NOT WAIT’

While Pennsylvania has drifted to the middle of the pack in the race for girls’ wrestling, New Jersey is trying to spring to the front.

Chris Ayres is the head coach at Princeton University and a staunch believer in the power of women’s wrestling. He and his wife Lori were driving forces in clearing the way for New Jersey’s first girls’ state tournament last spring.

New Jersey reacted the same way as the PIAA at first, but changed its position and started working cooperatively — and quickly — with Chris and Lori Ayres and other advocates in the state to come up with legislation that made sense.

The New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association altered its bylaws to categorize girls’ wrestling as both an individual and a team sport.

New Jersey cleared the way for the girls to wrestle in an individual state tournament without dwelling on the fact that bylaws stood in the way of the team component, according to NJSIAA assistant director Bill Bruno. The bylaws dictated that 20 percent of around 400 schools in New Jersey must have a girls’ wrestling team before a team championship can be established, he said.

Instead of waiting on action on the team portion, the NJSIAA acted right away on the individual piece. Bruno oversaw that progress.

“We said, ‘Let’s not wait. Let’s go ahead and sanction it as an individual girls’ event,’” Bruno said. “I’ve been in athletics all my life. Sometimes if you wait, you never get it done. We said, ‘Let’s do it and see what happens, and we’ll worry about it later.’”

Bruno admitted that the NJSIAA bylaws afforded them flexibility the PIAA might not have. He also said he believes Pennsylvania might be closer than anyone knows to making girls’ wrestling happen.

“Their hearts are in the right place,” he said. “They want to do it. I just really think they’re locked into terminology.”

Lori Ayres isn’t as convinced.

“We started at the same time,” she said. “It’s sort of sad Pennsylvania is stalling to this degree. You provide the opportunity, and the numbers come. It’s what happening over and over again.”

WHAT’S HAPPENING ELSEWHERE

Kansas could be a better example for Pennsylvania because it has taken years of back-and-forth to clear the way for its first state championship.

The key in Kansas was that nobody pretended to have all the answers up front, and nobody was afraid of pitching ideas that would get laughed out of the room, said Nate Naasz, who who worked for the Kansas Wrestling Coaches Association at the time.

Coaches and administrators all worked together to clear one hurdle at a time, all while girls got the chance to compete.

“We’re coaches, so we wanted it to happen yesterday,” Naasz said. “We kept a really open dialogue in the state office and were working with multiple organizations around the state, and we proved it. Once they let us start having girls’ divisions at tournaments, all of a sudden it was, ‘I don’t have to wrestle against boys?’ The numbers kept creeping up and creeping up.”

Nebraska is another proud wrestling state that has had to be patient and chip away at progress, according to Ron Higdon, Assistant Director of the Nebraska School Activities Association. Higdon is confident the state will make its final push toward creating a girls’ championship with an upcoming vote on sponsorship in January.

“Why would we want to be the 47th state that does it?” Higdon asked. “People who say there’s not a need for it, that’s what they said in 1972 before Title IX. Look at what happened since then. We can’t wait another 20 years before we figure it out.”

THE OBVIOUS BARRIER

Bill Walizer, the varsity coach at Central Mountain, drove from Mill Hall to the girls’ tournament in Newport over the weekend. He brought two junior girls the morning after his program finished hosting King of the Mountain, one of the most rugged high school tournaments in the state.

Olivia Miller, a junior at Central Mountain, said she tried for years to convince her parents to let her wrestle. She said she wanted to continue to uphold her family’s proud tradition of wrestling.

When she did finally get the go-ahead, it took time for her brother and teammates to accept it.

“Some of the boys took it a little hard,” she said. “My brother said he was going to quit if I wrestled, but now we’re getting along better than we ever have before.”

Most of the girls wrestling at the Newport tournament probably have similar stories to tell.

Their obstacles are often less about the sport than they are the eventuality of wrestling boys. The older they get, the bigger that issue becomes.

“There are actually quite a few girls in my school who want to wrestle,” Miller said. “Their parents won’t let them or they’re too scared. I was scared at first, too, because I thought the boys would be not so nice, but then I finally did it.”

All parties can agree on at least one thing when it comes to the future of girls’ wrestling: Having girls wrestle boys is not in the best interest of anyone. Even the PIAA has a statement in its handbook that says mixed-gender sports “would have a chilling effect on female participation.”

“It’s not just the right thing to do with women, but the right thing to do for boys,” said Terry Steiner, the U.S. women’s national team coach. “Don’t put a boy in that situation, a young freshman who hasn’t hit puberty yet and he doesn’t have that man strength yet. You’re going to make him wrestle a girl who might have matured earlier.

“It can be a very humiliating and embarrassing situation. On both sides of it, it’s the right thing to do to separate this.”

It’s hard to find two bigger believers than Chris and Lori Ayres in the benefits of girls’ wrestling, but even they had to pause when their daughter told them she wanted to wrestle.

“When my daughter wanted to wrestle, we were like, ‘What, really?’” Lori Ayres recalled. “Now, I couldn’t imagine who my daughter would be without this.”

Atkinson said he sees a disruption from girls at the youth level who reach high school and feel like they have no choice but to stop wrestling. And if that path forward is cloudy in the first place, how many girls choose to not wrestle at all?

“To me, the PIAA put us in a situation where we’re just going to be chasing our tails for a couple years,” he said. “In Souderton, I know I have legit girls that went through the middle school program, who are freshmen now and do not feel comfortable wrestling boys, and rightfully so. They’re going to go in the practice room and get torn up.”

WHAT’S NEXT

Shoving aside all the challenges, the big question is: Now what? Who is responsible for getting the numbers the PIAA needs to approve girls’ wrestling as a sport? Is it the coaches, or does the PIAA need to take a more aggressive position?

States work closely with USA Wrestling and the organization’s “secret weapon,” Joan Fulp, to organize and inform. Fulp pushed for over a decade to approve girls’ wrestling in the state of California and later became one of the most respected voices on both sides of the aisle.

Her message is one of persistence through the bylaws process within every state organization. She advocates for bringing up girls’ wrestling at every coaches meeting and every postseason tournament. Visibility and participation are key, she said, even if girls wrestle at events that aren’t sanctioned by the PIAA.

“[State organizations] work for their member schools, and they need to look at what their member schools want,” Fulp said. “They all have districts or sections. They all have representation at some point. That’s the pathway. Are you talking to coaches in all your districts? Are you finding out who to contact and work through those channels?”

And for their parts, Byers and Lombardi are watching closely and looking for the numbers required. If they see more tournaments and more girls participating in them, whether they’re sanctioned or not, those numbers could factor into the discussion that moves the sport forward.

“I think the legwork in all of this is just looking for competitions to exist that girls can participate in,” Byers said. “The way I see it happening right now is to have girls wrestle on the team, but offer non-school-affiliated events. You’re not going to represent your school, but you’d be there as an AAU club or as private citizens.

“Build up enough events and have enough kids participate, then turn the switch. For all these schools that have to build up participation, it’s going to take actual competition.”

Wrestling as a whole is fighting to preserve numbers, rather than pushing for growth. Women’s wrestling has energy and enthusiasm that can keep participation moving in the right direction.

The states that aren’t embracing girls’ wrestling are missing out on that opportunity, Lori Ayres said.

“The energy for girls’ wrestling is at an all-time high right now,” she said. “I don’t understand why Pennsylvania isn’t part of that. When you look at the map of the states that do have it, it’s to the point of embarrassment. There are people upset about it. They’re kind of being stonewall-ish.

“Girls wrestling should be on every agenda. It should be discussed at every state meeting. Wrestling numbers are low. It’s saving the sport.”

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.