By Ana Veciana-Suarez

Miami Herald

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) While the sharing economy may be run by millenials, that doesn’t mean older folks aren’t taking part in the on-demand revolution. A 2015 report by professional services and accounting firm PwC found that 25 percent of Americans 55 and older consider themselves providers in the sharing economy. In comparison, 7 percent of all Americans do.

MIAMI

After a long nursing career, Gerry Bradley, 82, still needed to supplement her retirement income. So she tried different freelance jobs before settling on DogVacay. Now she’s a sought-after sitter who specializes in special needs dogs.

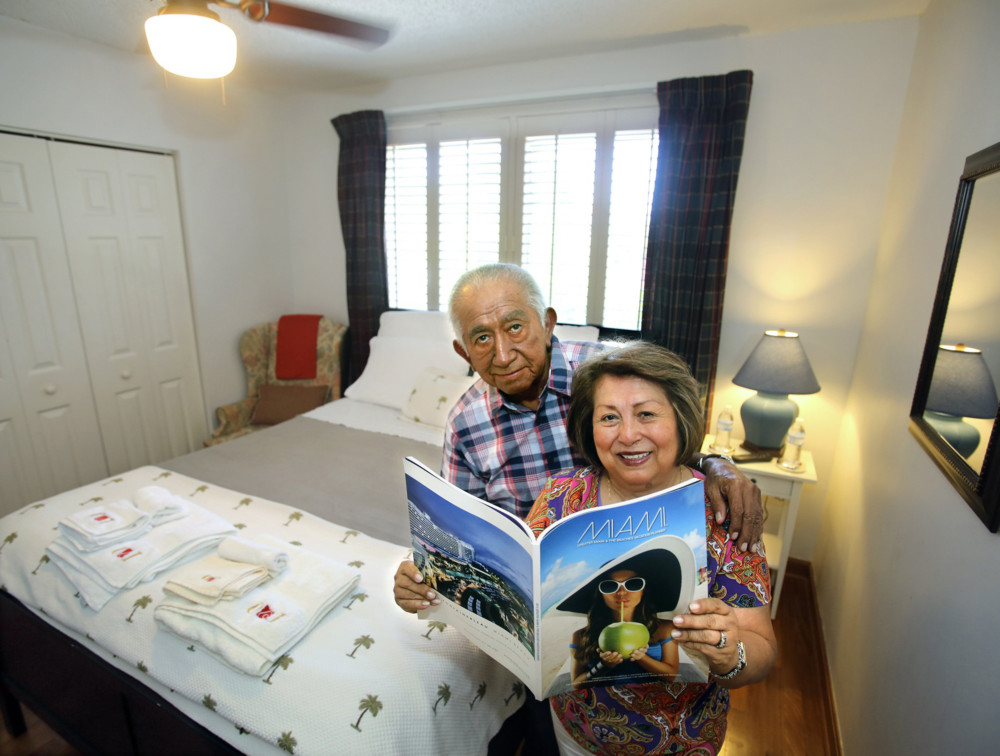

Olimpia and Ismael Yataco knew they needed financial help when Ismael got sick and his television repair business tanked. They turned to Airbnb and now rent three rooms in their four-bedroom West Kendall, Fla., house.

And Patricio Suarez, a 74-year-old former executive, was so bored with retirement that he began hunting around for something to keep him busy. He discovered Uber and began driving tourists in his 2014 Ford Explorer.

These Miami retirees are part of a growing group of seniors participating in the sharing economy by using their time, talent and assets to enhance their income and social lives. Eschewing traditional part-time work and going indie, they’re renting out spare bedrooms, offering up the use of idle cars and using their deep well of knowledge to make an extra buck, or to keep a toe in the workaday world.

“The sharing economy is a great fit for people [in retirement],” said Adam Sohn, AARP’s strategic engagement and media vice president. “They have all these assets and skills accumulated over a period of their careers and now they can offer them at their convenience, working as much or as little as they want.”

A 2015 report by professional services and accounting firm PwC found that 25 percent of Americans 55 and older consider themselves providers in the sharing economy. In comparison, 7 percent of all Americans do. Those numbers will likely increase as peer-to-peer gigs work out their kinks and baby boomers, who are more comfortable in the digital world than their parents, continue to retire. In fact, another PwC report forecasts the sharing economy to grow to $225 billion by 2025, up from $15 billion in 2014.

But while the sharing economy is “ideally suited” for retirees, a number of challenges remain, notes Nathan Hiller, associate professor and academic director for Florida International University’s Center for Leadership. For one, most of these peer-to-peer platforms are not regulated. Older adults also may not be as comfortable connecting with strangers. And “there’s still some reluctance about doing business when there’s not a number to call to get an issue resolved.”

Still, figures from companies underscore the interest of older adults in renting out what experts call “underutilized assets.”

A report from Airbnb, for example, shows that hosts 60 and older are the fastest-growing age demographic for the company, and senior women make up almost two-thirds of all senior hosts, receiving a higher percentage of five-star reviews than any other age and gender combination. Most of them, the report found, are empty-nesters who earn just under $6,000 from the rentals.

Uber estimates that 1 in 4 drivers is 50 or older, and DogVacay, which pairs sitters with pet owners, reports older adults are its fastest growing segment of hosts, with 25 percent or sitters 50 years or older.

“What seems to attract this demographic,” said Aaron Hirschhorn, co-founder and CEO of DogVacay, “is that it fits in with their lifestyle. It folds right into whatever they’re doing.”

In other words, there’s no need to commute, to invest in an office wardrobe or even spruce up tech skills.

That was true for Bradley, who had done some private duty nursing before she discovered DogVacay three years ago. A dog lover, she liked the idea that the company not only provided insurance but also handled payments, taking a nominal fee for making arrangements. Now most of her clients are repeat customers, and she prides herself on adapting her nursing skills to four-legged patients. She has cared for a dog in diapers and one that had to be fed with a syringe.

“If Fluffy sleeps with you, he’ll sleep with me, too,” she said.

Bradley, who calls DogVacay a life changer, arranges meet-and-greet with prospective clients to make sure they are the right fit and to dispel any doubts pet parents may have about leaving a family member behind. She charges $30 a day for her services, but longer-term stays get a special deal.

“I’ve made thousands of dollars over the years,” Bradley added. “It’s given me wiggle room between my pension and Social Security.”

Steve Webb, head of community at Turo (formerly RelayRides, which allows car owners to rent out their wheels), has noticed more retirees using their “idle assets sitting in the garage” to improve retirement income while also helping to defray the cost of auto ownership.

“People are living longer and they need to think creatively about revenue streams,” Webb said. “This can serve as a supplement and it’s employing something that is not being fully used.” The average active host can make about $600 a month, depending on the kind of car and how often it is rented out.

Whether renting out a car or a room, several hundreds of dollars a month can make a big difference for older adults strapped by low-yielding investments and a rollercoaster stock market. For Olimpia Yataco, 69, and husband Ismael, 76, the income they make off Airbnb has been “a miracle. It’s like something from heaven. It has changed our lives.” The couple signed up to host guests in October 2013, months after finding out Ismael had lung cancer. Their son, who uses Airbnb when he travels, had gushed about the service.

She admits she wasn’t initially sold on the idea of allowing strangers into her home but now loves the concept, and Airbnb considers her a Super Host, for her 350-plus positive reviews. She requires a two-night minimum stay, keeps strict rules, no alcohol, no smoking, and charges guests according to company guidelines, depending on the size of the bedroom.

“We’ve had guests from all around the world,” she said, “and not had any problems. It’s a nice addition to our lives.”

Not everyone in the sharing economy does it for money, however. AARP’s Adam Sohn views the “fluidity” of the sharing economy as a form of empowerment for this group of potential workers who might find their job opportunities limited. “It fills a void for both sides,” he said. “It’s more than just about the money. It’s also about engagement.”

For example, at care.com, which connects caregivers to those who need services, Jody Gastfriend, vice president of senior care at the platform, has found that engaging with others is a big attraction for workers. About 60 percent of older caregivers are women, and they tend to gravitate less to the jobs that require some form of physical effort and more to companionship duties.

“When people retire, they don’t anticipate the sense of disengagement that comes from not being around people all day,” Gastfriend said.

Patricio Suarez, a former minister of tourism for Ecuador whose family once owned a liquor factory, understands that feeling. He discovered that sitting around the house, waiting to be needed by his family, bored him. So after doing a little research he took up driving for Uber, ferrying people to PortMiami on weekends and hotel guests to the airport for their morning flights.

“It’s the best therapy in the world,” he said. “I haven’t had a bad experience, not a one. It’s amazing the life stories you hear just by asking the question, ‘What do you do for a living?'”

Most Uber drivers he’s met are retired professionals like him, or divorced women trying to make an extra buck to help with household expenses. Suarez uses the money he makes ($60 take-home for every 100 miles he drives) as his travel fund. Last year he and his wife spent a month in Europe. This summer they went to Maine.

“If I have to take my granddaughter somewhere or I need to do something, I don’t work,” Suarez said. “It’s the kind of job that gives you freedom to have your own life.”

While there are many advantages to the sharing economy, most companies provide insurance, screening and an effortless way to pay without actual cash exchanging hands, some observers warn that providers may be bearing more risks than they know. Hosts and drivers assume the wear and tear on homes and cars, and it can take only one bad experience to ruin months of good reviews.

What’s more, these gigs don’t offer traditional benefits, such as health insurance, which can be a problem for the under-65 set.

Nevertheless, the seniors taking up these gig don’t expect to strike it rich renting out their kids’ old bedrooms. They simply want a revenue stream that also provides flexibility.

“We see people who want to work but without the intensity and pressure of a regular job,” Gastfriend of care.com said. “They don’t want to be sidelined when they still have so much to contribute.”