By Marissa Lang

San Francisco Chronicle

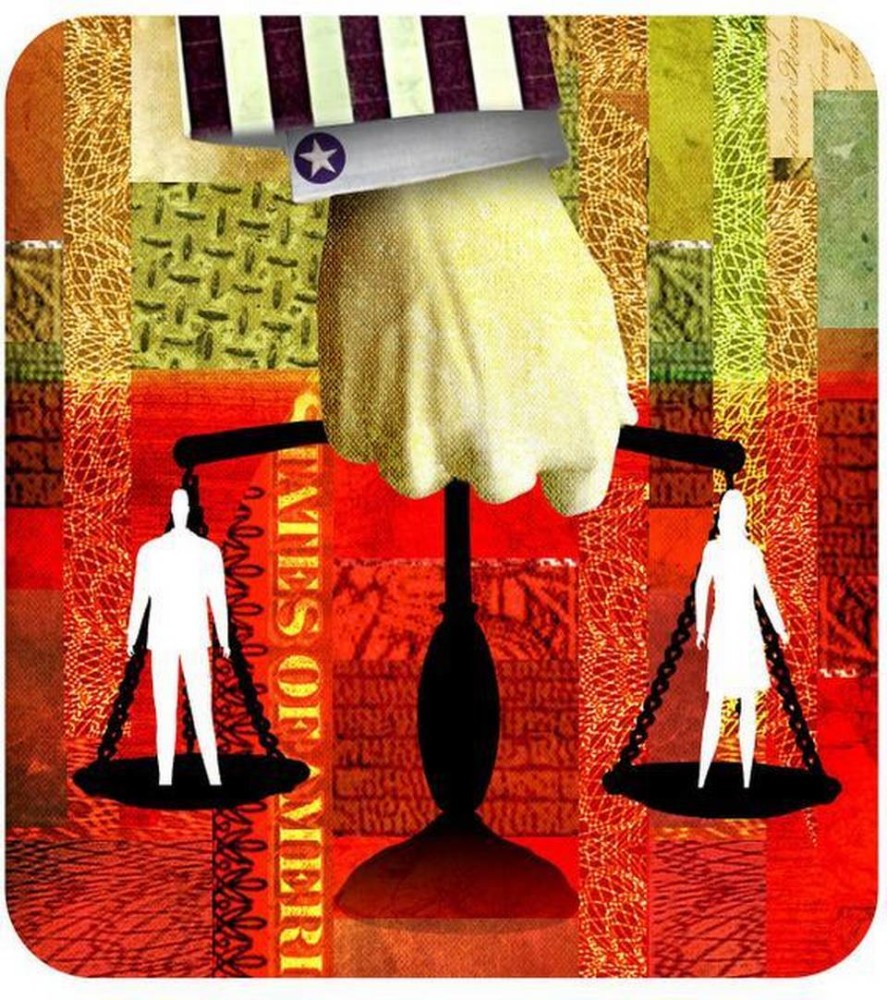

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) In a Stanford University-backed survey of women in business with at least 10 years of experience in Silicon Valley, 90 percent said they have seen sexist behavior at company off-site events or industry conferences. The Elephant in the Valley project included responses from 200 women, about a quarter of whom were C-level executives and 11 percent of whom worked in venture capital.

San Francisco Chronicle

A recent lawsuit claiming that a prominent venture capitalist sexually and physically abused a woman for 13 years — then reneged on an agreement to pay her $40 million for her suffering and discretion — has left many shocked and appalled.

But for many women who have worked in and among Silicon Valley venture capital firms, the news was less surprising.

They see the scandal, while extreme, as an affirmation of the sexism and misogyny they say has long pervaded the VC industry and an example of behavior and attitudes they have encountered.

Sequoia Capital, based in Menlo Park, has tried to distance itself from the accusations against Michael Goguen, who announced his resignation as a managing partner after reports of the lawsuit first surfaced. The firm, which has backed Silicon Valley companies Apple, Cisco, Google and Yahoo, said it asked Goguen to step down.

“I don’t want this lawsuit, and (Sequoia) pushing out a partner, to make it look like this is an isolated problem,” said Robin Wolaner, a former tech startup founder and executive now at We Care Solar, a Berkeley nonprofit. “It may be extreme, but it is not at all isolated.”

“This is as patriarchal as any industry could be imagined to be,” said Rebecca Eisenberg, a compensation negotiation lawyer and founder of Private Client Legal Services. “Women are not respected or viewed as equals. It is not a meritocracy. It’s about who are the male VCs comfortable hanging out with.”

Typical of VC firms

Sequoia Capital is one of hundreds of American VC firms that have no female investing partners. Less than a third of venture capital firms in the United States employ at least one woman to conduct business or participate in investment decisions, according to the Page Mill Publishing study issued last year that underscored a long-standing problem with the VC industry’s diversity.

And the problem has gotten worse, not better. Babson College’s Diana Project estimated in 2014 that 6 percent of venture capitalists are women, down from 10 percent in 1999.

In response to the industry’s dismal diversity record, the National Venture Capital Association, which advocates for the industry, established a task force in 2014 to expand venture capital opportunities for women and underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities and has recently expanded its own board to include more women. About 30 percent of the NVCA board is now female.

“Obviously when you look at an industry with the number of women at 5 percent, plus or minus, that is not at all where we mean to be,” said Kate Mitchell, an NVCA board member and co-founder of Scale Venture Partners. “We want to take it a level beyond creating opportunity for women to where we, as an industry, see women and underrepresented minorities as an actual asset.”

Lawsuit against Goguen

The NVCA declined to comment on the Goguen case, whose details have drawn national media attention.

Amber Laurel Baptiste filed a breach of contract lawsuit in San Mateo County on March 8 that accused Goguen of entering a physical relationship with her while she was a teenage victim of human trafficking, and continuing to “sexually, physically and emotionally” abuse her for the next 13 years.

Baptiste said that she suffered the abuse because she had been relying on Goguen, and his financial support, to free her from the human traffickers to whom she owed money. The $40 million contract was drafted by Goguen’s lawyers, according to Baptiste’s court filing, as a means of compensating her for enduring “the horrors she suffered at his hands” and keeping quiet.

Goguen admitted in court documents that he had a sexual relationship with Baptiste over the course of three marriages, and that he had agreed to pay her $40 million for her discretion. He denied all allegations of abuse and mistreatment. In his countersuit, Goguen said he made the first payment of $10 million because he was being extorted, harassed and threatened by Baptiste, whom he described as a vengeful woman “consumed by anger, obsession and jealousy.”

Sequoia said the lawsuit caught the firm by surprise.

“We didn’t learn about these claims until March 10, after they were filed in court,” the firm said. “We understand that these allegations of serious improprieties are unproven and unrelated to Sequoia. Nevertheless, we decided that Mike’s departure was the appropriate course of action.”

Goguen has since stepped down from nearly a dozen boards where he served as Sequoia’s representative.

The revelations regarding Goguen underscored for many what they say is a prevailing industry attitude toward women — in and out of the office.

The VC boys’ club

In an interview last year with Bloomberg, for instance, Sequoia Capital Chairman Michael Moritz was quoted saying the firm would consider hiring women — so long as doing so didn’t require it to “lower our standards.”

The year before that, VC firm CMEA Capital spent an undisclosed amount of money to settle a sexual and racial harassment lawsuit with three female former employees that accused a former partner of commenting lewdly about his co-workers’ bodies, watching pornography in the office and making unwanted sexual advances.

In a Stanford University-backed survey of women with at least 10 years of experience in Silicon Valley, 90 percent said they have seen sexist behavior at company off-site events or industry conferences. The Elephant in the Valley project included responses from 200 women, about a quarter of whom were C-level executives and 11 percent of whom worked in venture capital.

Nearly two-thirds of those polled said they had been sexually harassed. And three-quarters said they had been asked about their family life, marital status and children during professional interviews.

“Seeing women be hard-driving and get treated like your equal is a major and significant experience for a man,” said labor economist and Stanford Professor Myra Strober. “Men who see women’s only role as a one thing — being at home, being a wife or a mother — treat women who they work with differently.”

Attorney Eisenberg held top legal positions at PayPal, Pure Digital Technologies and Trulia — all three funded by Sequoia. S

he helped take PayPal public in 2002, then negotiated the $590 million sale of Pure Digital, the maker of Flip handheld video cameras, to Cisco in 2009.

Disputed remark

After the Pure Digital sale, Eisenberg said, Moritz invited her to a meeting to discuss her career. She told him she wanted a job — at Sequoia.

“He looked at me and said, ‘I just don’t know what I would do with someone like you here,'” she said.

Moritz “categorically denies” making the comment, a Sequoia representative said.

Christina Noren, an entrepreneur who’s been the CEO and founder of multiple startups, said she’s seen women passed over for jobs because of their gender since the start of her career. She said the attitude in venture capital has gotten worse over time.

“It’s gone from dismissive to downright nasty,” she said, citing an interaction several years ago with partners at a Silicon Valley VC firm. “I was told point-blank that I need to be more sensitive to male egos and how they feel when they’re corrected by a woman.”

Another female chief executive, who asked not to be identified for fear of repercussions for her venture-backed company and employees, said when she made partner at a San Francisco venture-capital firm, her male colleagues chided her for attending partner dinners.

“They’d be like, ‘You should really be home with your kids. Are you sure it’s a good idea for you to be working? Because your kids need you at home,'” she said.

“There is a latent unconscious bias in an industry like venture capital such that if you ask most people do they feel they’re racist, do they feel they’re sexist? They will answer that they don’t,” Strober said.

The high-profile gender-discrimination case brought against VC firm Kleiner Perkins by then-partner Ellen Pao in 2012 sparked a nationwide conversation about what happens in tech when diversity is ignored. Under pressure from news outlets and employees, Google, Facebook and Pinterest started releasing their workforce demographics and making plans to improve representation of women and minorities.

Incentivizing diversity

Few of the venture-capital firms that have backed these companies have followed their lead.

“No one has held them accountable,” Wolaner said. “Until they start losing out on investment deals or getting pressure to diversify from investors, it’s not going to change.”

Strober, who has worked with companies on diversity issues, said making diversity a priority means giving people an incentive to diversify.

“The person in charge has to be 100 percent behind this,” the professor said. “So, if the CEO says, ‘I want you to hire more women and I want you to spend time finding qualified women, and I’m going to make your bonus depend in part on how well you succeed in this,’ guess what? Everybody will fall in line.”

After prevailing in the Pao case, which aired the firm’s dirty laundry, including an incident where one male partner showed up at a colleague’s hotel room in a bathrobe, Kleiner Perkins began publishing its own diversity data.

In an onstage interview with Fortune writer Dan Primack in July, Kleiner partner John Doerr, who testified in the Pao case, characterized the victory as a Pyrrhic one and bashed his own industry for its record of excluding women.

“I believe this is an overdue conversation,” Doerr told Primack. “We collectively are pathetic on the issue. Six percent of the venture capitalists are female. You know as a matter of social justice, because it’s better for business, because it’s our values, that’s just dumb.”