By Wendy Lee

San Francisco Chronicle

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Attorneys suggest that from a legal perspective, part of the challenge in cases involving electronic communication is that the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which governs what is private, came into existence before text messages and Facebook and therefore is outdated. The law protects email as private. But spouses who openly share passwords with each other could likely use intercepted text messages as evidence in a legal proceeding.

San Francisco Chronicle

James Phills uncovered details about his estranged wife’s romance with his boss through private Facebook messages he wasn’t meant to see.

The messages were sent between his wife and the dean of Stanford’s Graduate School of Business in 2012.

But Phills, a Stanford professor at the time and now an Apple employee, said in court documents that he saw some of the messages because his wife, Stanford Professor Deborah Gruenfeld, had stored her passwords on Phills’ devices.

She and Phills were separated at the time, and she has said she did not give him the passwords.

It’s a messy case, but it points at a simple truth: the ability to store passwords on multiple devices carries privacy risks.

It’s convenient, allowing people to access text messages and notifications across smartphones, computers or tablets all at once.

But it also sometimes enables family members and friends to see private messages, especially on shared devices like a tablet or computer.

On a mobile device, messages may flash up on the screen even when it’s locked — a feature widely adopted for reasons of ease and speed.

“A person needs to decide whether they want convenience or whether they want to maximize privacy,” said John Simpson of privacy advocacy group Consumer Watchdog. “Many people forget that convenience comes at a price.”

Sharing devices or passwords can result in innocuous discoveries, like what holiday gifts a family member is purchasing.

They can also show when people cheat. Pop singer Gwen Stefani apparently became aware of an affair between her husband, Gavin Rossdale, and a nanny through flirty text messages that appeared on the family’s iPad, which was linked to Rossdale’s cell phone, according to Us Weekly. The two recently divorced. Representatives for Stefani and Rossdale’s band, Bush, did not return requests for comment.

“Once you have that pattern of sharing all of your passwords and email information and everything else, particularly with a spouse, you have a lesser expectation” of privacy, said Kresta Daly, a criminal defense attorney in Sacramento.

In court documents, Gruenfeld said she believes Phills invaded her privacy in late 2012 and early 2013.

Phills said he set up Gruenfeld’s Facebook page for her and she never changed the password. Having the Facebook password automatically loaded onto Phills’ iPad would have given him the ability to look at her Facebook page and messages. Gruenfeld said she would have changed her password had she known he could access her accounts.

“I didn’t know (Phills) had access to my private correspondence, and I never gave him permission to access it, read it, copy it for his personal records or disseminate it,” Gruenfeld said in court documents filed in her divorce case.

Phills said in court documents: “I did not violate (my) wife’s privacy because it was our practice during marriage to share our passwords.” She left herself logged in to email and Facebook on his devices, he said.

The divorce proceedings between Gruenfeld and Phills are ongoing.

In addition, Phills has filed a civil suit against Stanford University and Phills’ former boss, Garth Saloner, for wrongful termination because he believes that the romantic relationship between Gruenfeld and Saloner, then the dean of Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, colored decisions regarding a home loan from Stanford and Phills’ employment at the university. (Stanford has denied this, and Saloner called Phills’ lawsuit “baseless” in a 2015 email to faculty and students.)

The Facebook messages and emails between Gruenfeld and Saloner that Phills said he accessed through automatically stored passwords on his devices are being cited as evidence in court documents. Saloner stepped down as dean in 2016 and remains a professor at the university, as does Gruenfeld.

Gruenfeld, Saloner and Phills declined to comment.

From a legal perspective, part of the challenge in cases involving electronic communication is that the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which governs what is private, came into existence before text messages and Facebook and therefore is outdated, some attorneys said.

The law protects email as private. But spouses who openly share passwords with each other could likely use intercepted text messages as evidence, Daly said.

Smartphones have also been modified to display text messages on a screen even when the devices are not in use, and the act doesn’t apply to those situations, said Ed McAndrew, a data security lawyer at the law firm of Ballard Spahr. Leaving an iPhone with a text message appearing on the screen is similar to having a document open on a laptop in a public space, he added.

In California, a no-fault state where spouses do not need to prove wrongdoing, text messages indicating cheating would probably not impact the settlement amount in a divorce. Community property generated during the course of the marriage, such as homes and cars, are evenly split regardless of an affair, divorce attorneys said.

However, such messages could impact custody of children if they reveal drug use, said Adam Gurley, a San Francisco divorce attorney.

Already, attorneys are using information online, including what’s on users’ private Facebook pages, as evidence in court.

Photos could help place someone at the scene of a crime, and a list of friends could help attorneys identify relationships with other people involved in the case.

Attorneys can often get to information on a user’s private Facebook page by persuading acquaintances to help.

“I don’t think people really consider how easy it is to access that information,” Daly said. “It’s not as private as they think it is.”

Daly recalls that one time when a married friend she was visiting with left the room, she saw a text message flash across his Mac’s screen between him and someone with whom he was having an extramarital relationship. (The friend’s Mac was set up to display messages sent to his iPhone.)

“You need to fix that,” Daly told her friend when he returned to the room, referring to the message-sharing setting.

Adding more security measures to accounts is important but can be a hassle. Some services, like Gmail and Facebook, let you remotely disable account access on specific devices.

Others might require you to gain access to the device and log off. You can also change your password, which will force others to log in before they can get access again.

Many security experts also recommend consumers sign up for two-step or two-factor authentication for better password protection.

That requires users to enter their password and an additional code that is texted to their phone when their account is accessed from an unfamiliar place or device. This would not help those sharing passwords on a commonly used family device.

There are also old-fashioned ways of keeping information secure, like talking to people in person rather than texting them, experts said. (Another idea, of course, is behaving well and not cheating.)

“If you really don’t want something read by anybody else, don’t put it on the Internet,” Simpson said.

Google, Apple and Facebook have added features to make text communications more private. Facebook’s Messenger and Google’s messaging app Allo let users send encrypted messages that disappear after a period of time.

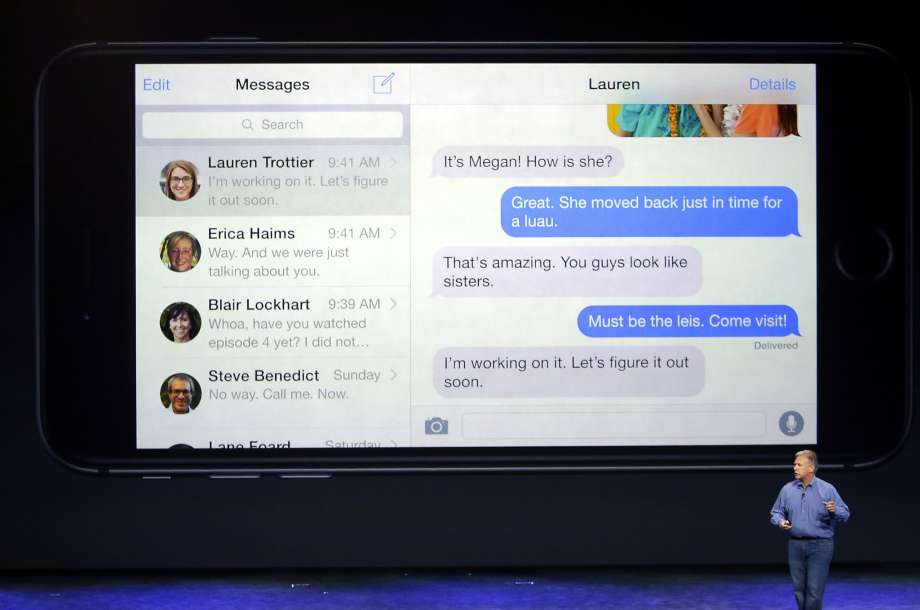

In Facebook’s case, the feature works only with a single device, which would prevent the secret messages from proliferating across devices logged in to the same account. Apple’s iMessage has a feature called “invisible ink” that obscures a text message. Users can also use an app called Confide to send messages that self-destruct through iMessage.

Experts caution that even if the text messages disappear or are erased, it’s possible that someone could take a screen shot of the message on some services. Gruenfeld deleted some of the Facebook messages between her and Saloner, but Phills had already taken screen shots of the exchange.

The technology makes for fertile ground for pranksters. Michael Piech, a 31-year-old Bay Area entrepreneur, sent a flirty text message as a practical joke in 2011. Piech knew that his friend Danielle Preiss would be borrowing her mother’s old cell phone so he sent a text posing as a man who was having an affair with the mother. “I have to have you. Same location as usual, 8C?” the text said.

Preiss had already been receiving text messages meant for her mother earlier that day, so when she saw the flirty text, she took it as real.

“I felt a pit in my stomach and thought the bottom had dropped out of my world as I knew it,” Preiss wrote in an email.

Then, after looking carefully at the number, she realized it was Piech.

“She was pretty upset,” said Piech, who splits time between New York City and Mountain View, where he works at a startup. “My area code gave it away.”

____________________________________________________

Wendy Lee is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer.