By Russell Grantham

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

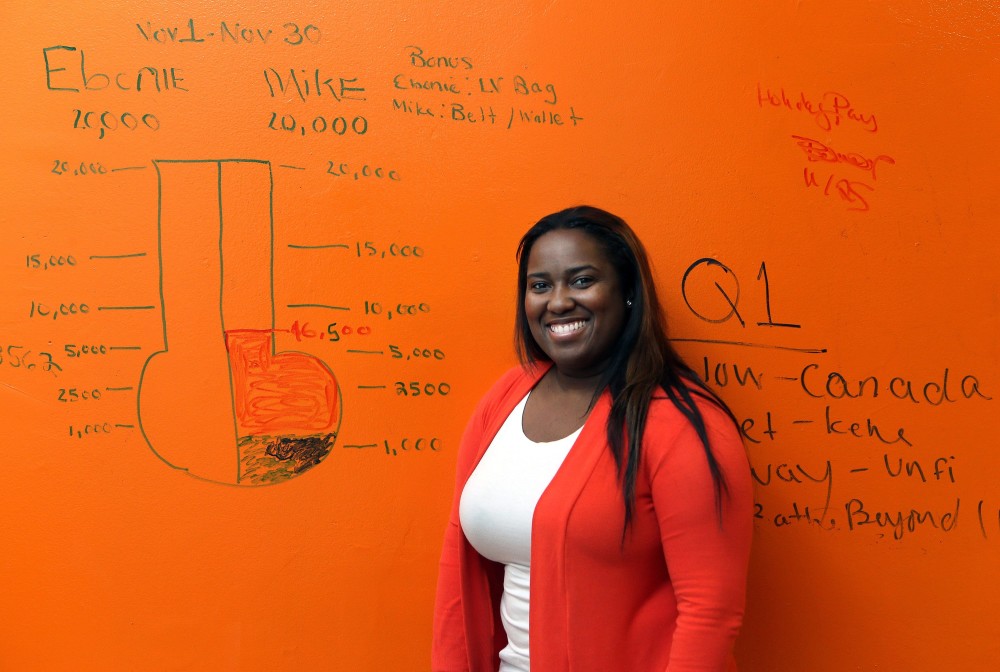

When Erica Barrett launched her own food company three years ago after winning a cooking contest, she had no idea she’d someday be selling her gourmet pancake mixes in Canada and the United Arab Emirates.

“I never imagined us working with exports,” said the 31-year old entrepreneur as workers at her small factory near Avondale Estates, Ga., scooped blueberry pancake mix into pint-sized cartons that might soon appear on QVC’s TV shopping network or store shelves in Dubai.

buy viagra oral jelly generic buy viagra oral jelly online no prescription

“Now we look at ourselves on a global basis,” she said. “We want to compete with the big boys.”

Spring-boarding off the domestic economy’s recovery since the Great Recession, small firms like Barrett’s 20-employee company, Southern Culture Artisan Foods, have been taking the plunge overseas to take advantage of rising incomes and demand for American foods and other products, experts say.

Online marketing has made it easier for even the tiniest firms to reach customers on the other side of the globe. Also, many firms in the U.S. are being helped along the way by an array of federal and state government programs that provide market research, advice, loans, insurance, subsidies to attend international trade shows and other aid.

Owners of small businesses “have thought for so long that exports are only for the big businesses. What we’re saying is that’s not necessarily true anymore,” said Terri Denison, Georgia district director for the U.S. Small Business Administration in Atlanta.

According to the latest data available from the U.S. Department of Commerce, small and medium-sized firms total 98 percent of all exporters.

Still, most small manufacturers and businesses focus exclusively on local markets.

The complexities and risks of dealing with another country’s tariffs and regulations, translating product labels into another language, understanding differing customs and tastes, and figuring out how to get paid on a timely basis can intimidate many would-be exporters.

Jerry Hingle, executive director of the Southern United States Trade Association in New Orleans, said the risks are overblown.

Many small businesses discover that exporting their product is worth the trouble after they’ve tapped overseas markets that bring them fatter profit margins and make them less dependent on U.S. customers, he said.

“Once they get their feet wet, they’re thrilled,” said Hingle. “The beauty is when the market here is saturated,” they can go overseas.

SUSTA, as Hingle’s organization is called, is a nonprofit funded mostly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It is part of the alphabet soup of federal and state programs aimed at helping smaller companies expand internationally especially since President Barack Obama’s 2010 pledge to double the nation’s exports by the end of next year.

U.S. exports have risen about 40 percent since then, to $2.2 trillion last year, but seem unlikely to hit the president’s $3.2 trillion target. “Doubling was very ambitious,” said Hingle.

Whether the president wins bragging points or not, small businesses meanwhile can choose from an array of government programs set up to boost exports some rather generous.

SUSTA helps about 400 companies a year in southeastern states with grants of up to $300,000 each. The grants cover half of eligible companies’ costs to sell overseas, including marketing and travel costs to go to international trade shows.

The federal Export-Import Bank offers loans and trade insurance to help finance the cost and lower the risk of transactions with overseas buyers.

The SBA, likewise, offers loan guarantees for banks’ export-related loans to small businesses, including funding to cover the increased need for working capital while shipments are headed overseas.

Those agencies have also joined with the U.S. Commerce Department and state units, such as the Georgia Department of Economic Development, to create Export Assistance Centers, including one in Atlanta. These offices are staffed with trade assistants who help small businesses with many of the tasks of international commerce, including figuring out what will export well, doing market research and vetting potential customers.

The idea is to help businesses “have an income stream that they might not otherwise have had,” said the SBA’s Denison. “If you’ve got enough small businesses benefiting from programs like this, you’re going to benefit the greater economy.”

Barrett, whose company makes 13 flavors of pancake mix and several flavoring rubs for bacon, said she has taken advantage of most of those programs to turbo-charge her firm’s growth.

“It’s a free resource. Why not use it?” said Barrett, who expects her company’s sales to jump from $500,000 this year to $1.5 million next year. About one-fourth of her sales are from exports, she said.

SUSTA covered half her costs to go to several trade shows, helping her company expand to Canada and the United Arab Emirates over the past year. Several trade assistants and other state and federal employees in local and overseas offices helped with tasks such as picking the best markets, running credit reports on potential customers and scouting potential distributors.

“It makes you feel very secure in what you’re doing,” said Barrett. “All I need to do is manufacture and show up at trade shows.” In February, Barrett walked away from her first UAE trade show with a deal to distribute her pancake mixes in a 60-store grocery chain, which she hopes will boost her annual sales by $500,000.

She was planning to send her company back to the UAE for another trade show before year-end _ again with SUSTA’s help. They’ve “opened us to a whole new world,” she said.