By Heather Somerville

San Jose Mercury News

On a mission to prove that consumers will pay to have bread and milk delivered to their front door, Instacart is expanding across the country as it aims to right the wrongs of years of failed grocery delivery ventures.

Powered by a 20-something who practices extreme ocean sports, Instacart hopes to dominate Amazon.com Inc. in the grocery aisle by using computer systems founder Apoorva Mehta built from his San Francisco apartment.

“Even though it seems we’re doing groceries, we’re actually just building software,” Mehta said.

As ridesharing, restaurant delivery services and online shopping have trained consumers to expect instant gratification, grocery delivery is an area yet to be fully developed. But many are trying, including titans Google Inc. and Wal-Mart Stores Inc.

The fledgling Instacart has the backing of Silicon Valley venture capital powerhouse Michael Moritz, who is gambling for the second time on grocery delivery.

“We all held hands and prayed,” Moritz, chairman of Sequoia Capital, said jokingly about the firm’s decision to lead an $8.5 million investment into Instacart last summer.

That decision came almost two decades after Sequoia, under Moritz’s leadership, partnered with Benchmark Capital to put $10.8 million into Webvan, a high-profile grocery delivery business best known for its banner bankruptcy in 2001.

Sequoia owned 8.4 percent of the company when it went belly-up.

But in 2014, delivery companies have what Webvan could only dream of in the late 1990s: high-speed Internet in nearly every home, mobile devices in nearly every consumer’s hand, and software that can plan delivery routes and predict customer orders.

“I think Instacart is taking every lesson from Webvan. They have a pretty good shot,” said Peter Relan, chief technical officer at Webvan from 1998 to 2001 who now runs Menlo Park, Calif., accelerator Studio 9 Plus.

Danielle Weintraub of San Francisco said she gets groceries delivered from Instacart, Safeway and Google Shopping Express.

She was tired of sitting in traffic and battling for parking to pick up ingredients for dinner.

“I haven’t been to the store in a few months,” she said.

Other smaller players, including Peapod in Illinois and FreshDirect in New York, have been delivering groceries for years with meager success, experts say, but none have moved quite as brazenly as Instacart.

After launching in September 2012, Instacart in just over a year moved across the U.S., most recently adding service in Boston, and plans to expand to 10 new cities this year.

The company is not yet profitable, Mehta said, but in about a year was making “tens of millions of dollars in revenue.” He declined to release exact sales figures.

Mehta, 27, left his job as a supply chain engineer for Amazon, he didn’t work directly on its grocery service, AmazonFresh and came to San Francisco, where he found people using Craigslist and TaskRabbit, a website to outsource errands, to get groceries delivered.

He said he knew he could come closer to solving the delivery puzzle than his old boss Jeff Bezos did with AmazonFresh.

“I knew what AmazonFresh was doing was wrong,” he said. “It didn’t sit well with me. It wasn’t really solving the customer’s problem.”

Amazon uses a massive network of warehouses, distribution centers and trucks to store and move groceries, and requires that customers order several hours in advance of their delivery.

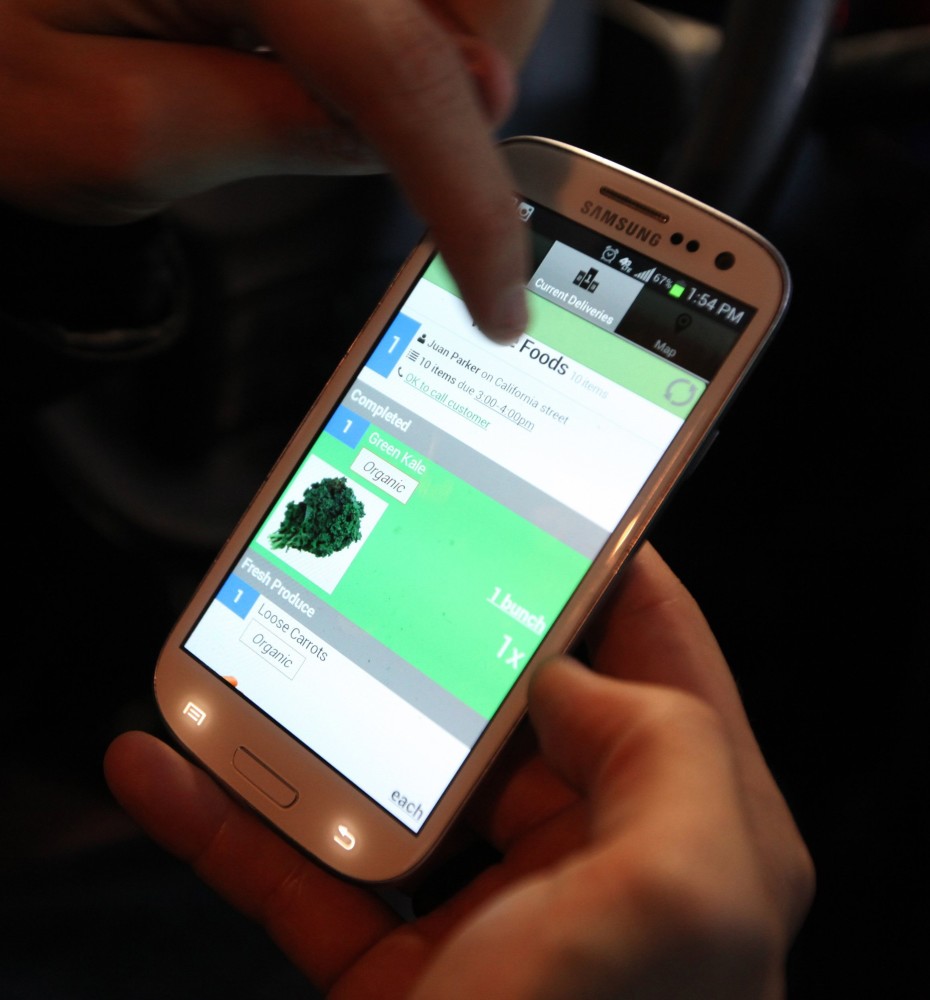

Instacart doesn’t own warehouses, and instead contracts drivers, similar to a ridesharing service, to shop at local chains for items customers have ordered and paid for online, and can deliver within an hour and late into the night.

“Because they have their own warehouses (of groceries), Amazon is limited in their selection,” Mehta said. “Imagine if you ordered your groceries and one truck leaves a warehouse two hours away and comes to your door to do one delivery of groceries. It just doesn’t make sense.”

But Instacart’s secret to early success may also be its eventual undoing, some analysts say. The startup sped ahead without any formal agreements with the grocery stores where it buys its customers’ orders, which means Instacart pays full price for groceries just like any other shopper, and its customers often pay above full price to make the business profitable.

“There are so many flaws in layering labor on top of the existing industry model, that I do not give them much chance without … getting cooperation from retailers and manufacturers,” said Tom Furphy, a former Amazon executive who helped launched AmazonFresh in 2007 and ran it until 2009.

Amazon owns and controls the prices of its groceries.

Grocery delivery has razor-thin margins, between 1 percent and 2 percent at the national chains, and there are plenty reasons for shoppers to go to the store themselves.

The Internet doesn’t let you shop for the exact ripeness of an avocado, and an Instacart courier may not check a carton of eggs for cracks.

“If you make one mistake out of 10, that ends up being a huge problem,” said Phil Terry, chief executive of Creative Good, a consulting firm that has advised online grocers since the ’90s.

Aware of the risks, big grocery delivery contenders Amazon, Google and Wal-Mart are moving cautiously, also trying to learn from Webvan.

Amazon hired four former Webvan officials to work on AmazonFresh, which launched in San Francisco last month.

It has moved slowly, expanding to California only after about seven years of testing around Amazon’s hometown of Seattle.

“We recognize the economics are challenging, so we will remain thoughtful and methodical in our approach to expanding service,” said Amazon spokesman Scott Stanzel.

Wal-Mart has been testing grocery delivery in the San Francisco Bay Area with minimal expansion since 2012.

Google Shopping Express started delivering groceries last fall in parts of the Bay Area after spending nearly a year working to perfect algorithms that calculate the quickest delivery routes and track store inventory.

Google also spent that year enlisting retailer partners, and some of those stores say the service helps them compete with Amazon.

But Instacart’s lack of agreements with the stores where it delivers, Berkeley Bowl, Safeway, Costco and Whole Foods in the Bay Area, has raised the ire of some grocers.

Trader Joe’s recently gave Instacart the boot from it stores, and a lawyer with Wendel Rosen, the firm representing Berkeley Bowl, said any appearance that the grocer had somehow approved of Instacart’s delivery would be damaging to its reputation.

Berkeley Bowl is concerned produce will end up at the customer’s door bumped and bruised.

Steve Blank, a Silicon Valley serial entrepreneur, startup adviser and professor at Stanford University, dismisses the backlash and said Instacart does not need the stores’ approval.

“Great startups do not raise their hand and say ‘Mother, may I?’ or else innovation would die,” he said. “Did Uber go ask every taxi commission? Did Airbnb go ask all the hotels?”

Mehta says Instacart is “very respectful” of retailers’ concerns and is in talks with grocers to work out a partnership. But a couple of retailers said they aren’t interested.

“The delivery service that we’re working with is Google Shopping Express, and that’s the only one,” said Whole Foods spokeswoman Beth Krauss.

She said she knew Instacart was shopping at some San Francisco Whole Foods stores.

Without cooperation from retailers, Instacart doesn’t have much chance of competing with Amazon’s lower grocery prices, Furphy said.

But with its $299 annual subscription fee in some areas, Amazon isn’t a bargain either, points out Fiona Dias, chief strategy officer of ShopRunner, an online shopping delivery service.

“Their market size will be limited,” she said. “Maybe they’ll make money by selling a camera or a sweater every so often. The economics of this is very much an experiment.”